Oscar-Nominated ‘War Witch’ Vividly Portrays the Horrors of War-Torn Congo

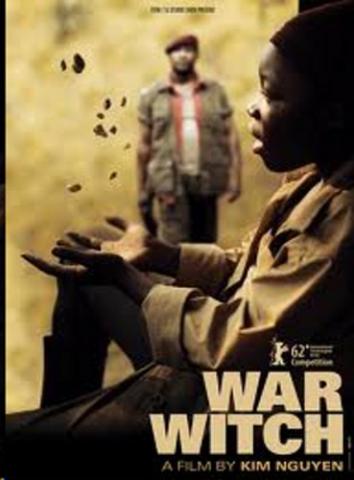

War Witch

Written & Directed by Kim Nguyen

Starring: Rachel Mwanza & Serge Kanyinda

In the madhouse of war, facts may not always speak for themselves. Art is required to create order from violent chaos. And fiction, rather than fact, opens us to understanding what the British poet and novelist Thomas Hardy said of mankind’s savagery: “While much is too strange to be believed, nothing is too strange to have happened.”

Now comes an important addition to artful portrayals of horror: Kim Nguyen’s existential film, “War Witch,” a French-Canadian production starring a remarkable actress from Congo-Brazzaville——16-year-old Rachel Mwanza, who was a street waif in Kinshasha for several years of her young, all too real life.

Written and directed by Mr. Nguyen, a Vietnamese-Québécois filmmaker based in Montréal, the movie milieu is the genocidal Congo wars of the 1990s and early 2000s, in which disease and starvation killed more than 5 million non-combatants. The focus of Nguyen’s tale is a girl named Komona (Mwanza), kidnapped at age 12 by a band of heavily armed thugs loyal to a warlord called Great Tiger.

Forced by her abductors to murder her parents——quickly, with an AK-47 assault rifle rather than watch them dispatched by a machete-wielding thug——Komona is spirited off to a jungle camp of child soldiers for further hardening and soul-deadening. There, she is taught that a gun is “your new mother and father.” She is put to work panning for gold nuggets in a river, entertained with nightly screenings of blood-soaked Jean-Claude Van Damme videos, and entranced by a slightly older boy skilled in magical grigri, whom she names Magicien.

Komona is herself named a “war witch” by Great Tiger when he discovers her ability to sense the approach of rival warlord armies——in part courtesy of Magicien’s “magic milk,” a hallucinogen extracted from tree sap that he and others drink to endure their lives as child soldiers. Komona, along with Magicien as companion and protector, escape Great Tiger’s camp and begin to confront and overcome shame for atrocities they were made to commit by the only means available to them: love.

Their romantic idyll is brief. When Great Tiger’s thugs relocate the pair, Komona is once more ordered to kill with an AK-47; this time, her husband Magicien (played by the young Congolese actor Serge Kanyinda). She refuses a commander’s order, and kneels beside Magicien as he is hacked to death, moments after telling Komona, “You are my wife——be happy.” The commander then takes Komona as his sexual slave——and eventually, at age 14, the imminent mother of his child.

But Komona escapes her rapist captor——by grisly means none too strange to have happened during the actual Congo wars——and attends to the business of simply surviving, along with giving birth in the wild and the more complicated matter of exorcising uninvited demons.

The leitmotif of “War Witch” is Komona’s talks with her unborn baby, at turns sweet and painful. At one point, she says to her belly, “I don’t know if God will give me the strength to love you.”

New life, even in the monstrosity of war, is one of many symbols and metaphors delicately employed in Nguyen’s screenplay. They serve as masterful contrasts to the facts of real and awful life of war-torn Congo.

Chief among metaphors is the casting of Serge Kanyinda in the role of Magicien: an albino, Kanyinda’s mere appearance reminds us that we regard certain people, and our sorry human capacity for war, as somehow apart from our collective experience; as somehow too strange to be believed.

As for Rachel Mwanza, who was abandoned to the streets by her parents, the producers of “War Witch”——Pierre Even and Marie-Claude Poulin, in addition to Nguyen——have seen to her housing and educational needs. In February, they engineered a special visa allowing Mwanza to attend the Academy Awards in Los Angeles on March 4 and the Canadian Screen Awards on March 3 in Toronto. At each ceremony, “War Witch” was a nominee for best film.

In Los Angeles, “War Witch” lost foreign film honors to the Austrian film “Amour.” But it swept the top awards in Toronto: best actor for Mwanza, best supporting actor for Kanyinda, best director and best original screenplay for Nguyen——and best picture. The best pictures tend to be the least expensive productions. “War Witch” was made for $3.5 million. And the best pictures begin with the very best in screenwriting.

Consider this gem of screen dialogue, as Komona instructs the infant growing inside her on the importance of sublimating grief in the struggle for a better day: “I had to learn to make the tears go inside my eyes.”

Author Bio:

Thomas Adcock is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.