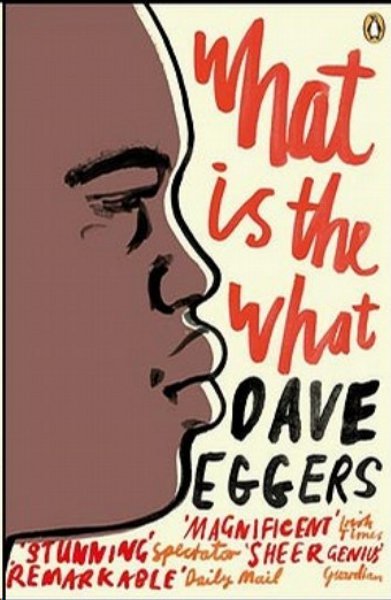

Literary Flashback: Reading ‘What Is the What’

Editor’s Note: In the “Literary Flashback” column, Kimberly Tolleson will look at modern literary works that may have been overlooked by readers or books that fell under the radar when they were initially published and are worth a read.

What is the What: The Autobiography of Valentino Achak Deng

By Dave Eggers

McSweeney’s

475 pages

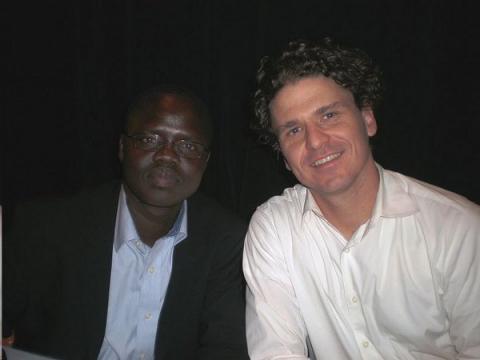

It may sound oxymoronic, or even presumptuous, that Dave Eggers could write The Autobiography of Valentino Achak Deng. Nonetheless, the dual effort of these two men produces a powerful story of Deng’s experience as a Lost Boy of Sudan and eventually as an immigrant in the US.

What is the What is a story of just one of the thousands of the Lost Boys, a group of refugees who escaped their hometowns on foot during the Second Sudanese Civil War starting in the 1980s. Almost every one of them young and orphaned, these boys walked from their destroyed homes in South Sudan through unbearable circumstances. Every day the group lost more children to hunger, disease, enemy fire, even lions and crocodiles, all while gaining more displaced boys along the way. Those who survived the 800-mile journey weren’t met with a much better situation once they reached their destination, a refugee camp in Ethiopia (and later, another camp in Kenya). After spending most of his childhood and early adulthood within the confines of refugee camps, Deng was one of the last of nearly 4,000 men to be flown to the US by the Lost Boys Foundation. Deng and Eggers originally planned to write a book from the Lost Boys’ perspective more generally, but then decided that Deng’s story was too rare not to stand on its own.

The book stirred up some controversy because of the line it draws between fact and fiction. Because Eggers wrote the novel for Deng, the autobiographical element is already once removed. And as with any memoir piece, dialogue has to be invented, chronology is altered, even certain characters are condensed, in order to create a more succinct and compelling read. Though some criticize Eggers’s attempt to write another person’s autobiography, it ultimately comes off as a triumph. This was not something that Eggers attempted lightly. He and Deng coordinated for three years—Deng telling his story, Eggers trying tirelessly to capture the voice, scenes and events as correctly as possible.

Their hard work paid off; not one moment of falseness appears throughout the nearly 500 pages. Deng gives a fair and humble warning in the book’s preface: “Because many of the passages are fictional, the result is called a novel. It should not be taken as a definitive history of the civil war in Sudan, nor of the Sudanese people, nor even of my brethren, those known as the Lost Boys. This is simply one man’s story, subjectively told. And though it is fictionalized, it should be noted that the world I have known is not so different from the one depicted within these pages. We live in a time when even the most horrific events in this book could occur, and in most cases did occur.”

Eggers splits the novel into a present narrative that takes place three years into Deng’s relocation in Atlanta, and a past narrative starting in Sudan. Deng was a happy 6-year-old with a large family when their village was raided by Arab militiamen from Northern Sudan; he was separated from everyone he knew while crops were burned, people were killed, and children were kidnapped to be traded as servants and sex slaves.

After finding other abandoned boys traveling on foot like himself, Deng started the long journey to Ethiopia. He enumerates the amount of tragedy he witnessed and experienced: “I have the fortune of having seen more suffering than I have suffered myself, but nevertheless, I have been starved, I have been beaten with sticks, with rods, with brooms and stones and spears. I have ridden five miles on a truckbed loaded with corpses. I have watched too many young boys die in the desert, some as if sitting down to sleep, some after days of madness. I have see three boys taken by lions, eaten haphazardly. I watched them lifted from their feet, carried off in the animal’s jaws and devoured in the high grass, close enough that I could hear the wet snapping sounds of the tearing flesh.”

The alternate narrative between past and present reveals that Deng still has much unforeseen struggling to do in America, even after he has been so fortunate to make it there in the first place. It seems only fair for Deng’s unfathomable 13 years of hardship in Africa to come swiftly and cleanly to an end once he’s stepped foot on American soil, given an apartment and a sponsor and a car – but this is far from the case. As Eggers writes in a separate essay: “In almost all cases, the young men had never had jobs, had never seen refrigeration (let alone ice), had never driven a car or been in a grocery store. The US government, which had done a very good thing by admitting thousands of penniless young Sudanese men into the country, had perhaps underestimated the difficulties they would experience in adjusting to life in America.

The refugees were given three months of financial support - about $800 - and thereafter were more or less on their own.” Deng knows little outside the world of his African refugee camps and has trouble adapting to American rules and culture. (The story opens up on Deng graciously allowing robbers into his home.) He suffers from several medical issues from his tumultuous past and has trouble with college classes and finding anything but menial work. He and his entire network of other relocated Lost Boys have frustrations about their transition to the US: “But while Sasha told us that in America even the most successful men can have but one wife at once—my father had six—and talked about escalators, indoor plumbing, and the various laws of the land, he did not warn us that I would be told by American teenagers that I should go back to Africa.” The Lost Boys, now men, are stuck in a country that is not as stable and peaceful as they hoped, missing a homeland to which they can’t return.

Deng had a story that he wanted to get out, “to serve as the specific that might illuminate the universal,” and Eggers was an impeccable vehicle for this daunting task. Deng’s story places us somewhere not many have written or read about, with an urgency and importance that still has much relevance years later. It is a work of empathy for the reader, often painful and incredible. Though it’s the type of book that is finished with a heavy sigh, readers can take heart in the foundation Deng has been able to set up since coming to the US. All proceeds from What is the What have gone to this organization.

Author Bio:

Kimberly Tolleson is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine and writes the Literary Flashback column.