Surrealism Beyond Borders: Global Dreaming at the Met

The Metropolitan Museum of Art has taken on a gargantuan task with Surrealism Beyond Borders. The exhibition not only embraces every aspect of the movement--from painting, sculpture, journals, poetry, film, radio, in short, any means of human communication that could project its principles—but also seeks to unravel on a worldwide scale its dreams.

Every movement of consequence, however far-reaching, has a beginning. Surrealism’s birth was full-blown from the mind of French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who in 1917 was quoted about this new spirit in the air thusly: “When a man wanted to imitate walking, he invented the wheel, which does not look like a leg. Without knowing it, he was a Surrealist.” But it was Andre Breton who appropriated the word in his Manifesto and set himself up for over 50 years as its leading proponent.

There’s a great irony at play in a group of predominantly European male poets and writers holding sway over the unconscious. True, in a post WWI climate, they had Freud’s writings on psychoanalysis as a springboard to the imagination, espousing automatic writing and drawing along with dreams as the way to exorcise reason’s control over the mind. But meanwhile, the creative impulse was playing out from Cairo to Cuba, literally anywhere where inspiration was determined to trump the establishment.

With such a wealth of images to confront, the visitor needs to doff his or her intuitive cap and let the pull of the subconscious mind have its way. Upon entering, arrivals are confronted with a large Magritte painting of partially shuttered windows, revealing a blue sky beyond. It’s a clever construct, promising a journey of infinite possibilities.

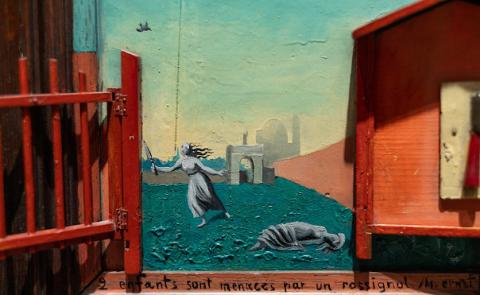

One of the first rooms displays three panels by Remedios Varo. In exquisite detail, she gives us nuns; angelic schoolgirls; a dark otherworld where her subjects seem to float towards a mountainous unknown. The artist’s story is not unlike many of the surrealists on display. Flights from the persecution of repressive regimes were commonplace. Varo moved to Paris in 1937, later finding that she could not return to her Spanish homeland following the Spanish Civil War. Escaping to Mexico from the growing threat of Nazi occupation, she befriended and collaborated with Leonora Carrington, another surrealist married to German émigré Max Ernst. A pleasant surprise is finding among so many expansive images, Ernst’s small work, Two Children Are Threatened by a Nightingale (1924) and Carrington’s Self-Portrait depicting a seated woman equestrian surrounded by horses real and imaginary.

If the female sex were largely objects of desire in the male gaze, this retrospective makes clear that the women who clambered aboard this enterprise could produce startling and powerful works. The American Dorothea Tanning’s Eine Kleine Nachtmusik (A Little Night Music) depicts young girls wandering a hallway in a somnambulistic state, a suggestive eroticism at play reminiscent of the Polish/French painter Balthus.

Brazilian Tarsila du Amaral’s Abaporu (1928) is a masterly work of such distorted figuration that a gigantic foot devours the canvas space, the head a miniscule afterthought. There are other key contributors, notably the documentary Swiss photographer Eva Sulzer and founder of Dyn, a surrealist Mexican journal that thrived from 1942-44.

One Spanish-born exile who became a key catalyst for fomenting surrealism in the New World was Eugenio F. Granell. He was not only a consummate artist but teacher, who along with Cuban painter Wilfredo Lam and others, including Breton, started making cadavres exquis (exquisite corpses) in their new home. (Exquisite corpse is a method by which a collection of words or images is collectively assembled. Each collaborator adds to a composition in sequence, by being allowed to see only the end of what the previous person contributed.) An example by Ted Joans is on view, an elongated accordion-like postcard creation sent to a global network of contacts.

For Granell, settling in the Dominican Republic under General Trujillo’s bloody dictatorship was short-lived. Granell found himself once again in exile, eventually finding a teaching position and acclaim at the University of Puerto Rico. This new freedom led to such works as The Pi Bird’s Night Flight (1952). His bird figure seems to elegantly drift, carrying its amorphous appendages across a midnight background.

There are several standout artworks worthy of mention, whether for the grotesqueries they portray or the coolly objective and disparate arrangement of their parts. Harsh depictions of women are evidenced in the Egyptian offerings, with the intent to criticize the oppression of the female gender and the role of prostitution in that society. Enrico Baj’s Body Snatcher in Switzerland pits a fairytale behemoth against a bucolic Swiss landscape. A nightmarish depiction of stunning beauty is the Nigerian Skunder Boghossian’s owl and cat phantoms swirling in a jewel-like space. Japanese painter Kogu Mayo has produced a quiet but unsettling universe in The Sea, with zeppelin, stray sea creatures, submarine and bathing beauty.

Salvador Dali is on view in the form of his black telephone, the handle overlaid by a pink lobster. Its inclusion is a humorous Dada touch to the more somber images encountered at every turn.

Even if the roots of surrealism began with the written word, it’s the imagery from 45 countries on view that ignites reaction. Undeniably, the ability to convey images of the subconscious through the evocative power of film is universally understood by contemporary audiences. Alfred Hitchcock and Orson Welles were successful proponents, as was Mexican director Luis Bunuel.

A sampling of short films on display deserve consideration, where filmmakers frequently used their actors as aimless wanderers, confronting the irrational, not unlike sleepwalkers on their private journey. An exception is Director Len Lye’s black-and-white animated hand drawings from 1929, detailing the kinetics of the human body.

A section devoted to the Chicago Surrealist group may come as a surprise to some. The tumultuous uprising during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago was fertile ground for their ideas, with one quarter of the assembled receiving the pamphlet “Surrealist Insurrection 3,” with its message of “Down with imperialist culture!” The movement had begun several years before, in the “Make Love, Not War” campaign. Their members were adamant that surrealism was no longer a thing of the past but an ongoing revolution.

The exhibition publication by curators Stephanie D’Alessandro and Matthew Gale sets a new standard in evaluating the lasting impact of the movement. Hopefully, those visitors who find themselves alternately curious and confused—even startled by such expressions in the name of art—will see that dreams can be a richly rewarding aspect of being human.

The exhibition is on view through January 30, 2022 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Image Sources:

Courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art:

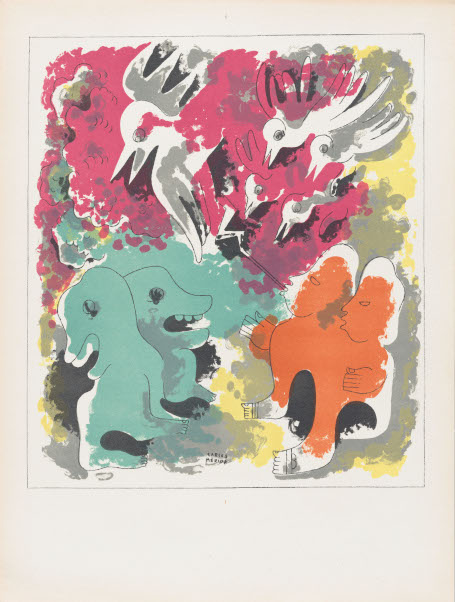

- Carlos Merida; Plate 7 (Prints from the Popol-Vuh)

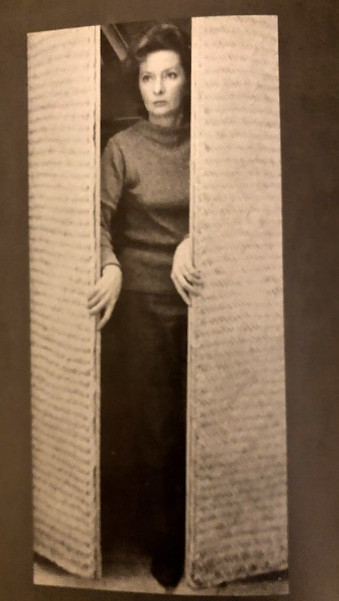

- Marcel Jean Armoire; Surrealist Wardrobe

--Steven Zucker (Flickr, Creative Commons)

--Herry Lawford (Flickr, Creative Commons)

--Cesar Cardoso (Wikipedia, Creative Commons)

--Pere Ubu (Flickr, Creative Commons)

--Nasch92 (Wikimedia, Creative Commons)