The Weird and Wonderful Literary World of Bob Dylan

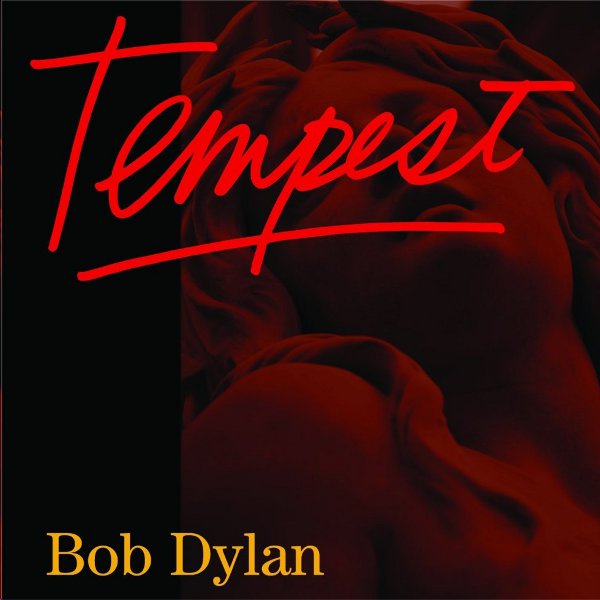

On September 11, 2012, Bob Dylan released his 35th studio album, Tempest. The reviews poured in, many hailing the album as an instant classic, and simultaneously labeling it Dylan’s darkest album to date, filled with tracks about death and disaster, including the nearly 14-minute long title track about the sinking of the Titanic. When the album’s title was revealed, a firestorm of speculation broke out, particularly among music historians and Dylanologists who hypothesized that Tempest might be the last album in the “Bard from Hibbing’s” 50-year career, as The Tempest was what many critics believe to have been Shakespeare’s final play.

Dylan swiftly denied these rumors, in his typically sardonic fashion, telling Rolling Stone, “Shakespeare’s last play was called The Tempest. It wasn’t called just plain Tempest. The name of my record is just plain Tempest.” Fair enough. Whether or not the title itself was influenced by Shakespeare in other ways we will likely not know until Dylan releases Chronicles Volume Two, the long-anticipated follow-up to his 2004 memoirs. After 35 studio albums, many live performances and bootlegs—and a tremendous collection of material released just in the past 15 years—it does lead one to wonder where Dylan continues to find the sources of inspiration that drive his imaginative and creative forces.

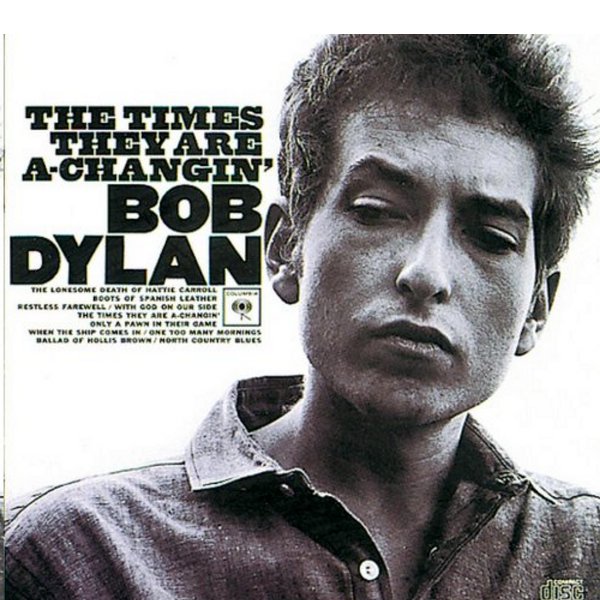

In Chronicles Volumes One Dylan writes, “Creativity has much to do with experience, observation and imagination, and if any one of those key elements is missing, it doesn’t work.” Chronicles offers readers a glimpse, albeit a somewhat foggy one, into the mind of Dylan the artist, into the world of art and experience that compelled the madly creative forces of genius that led to his first songs. Among the early influences Dylan discusses in his memoirs are his relationship with Suze Rotolo (the girl on the cover of Dylan’s second album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan), the works of Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill, the French symbolists (namely Arthur Rimbaud), and the music of Robert Johnson and Woody Guthrie (Guthrie’s book Bound for Glory was also a huge influence on Dylan). While early American blues, folk and rock and roll recordings have undoubtedly shaped Dylan’s music over the years, literature has also played a key role.

The literary characters, themes, and lines that have populated the world of Dylan’s musical landscape have been as deep and varied over the years as his references to history and the folk tradition. In his early years, Dylan was significantly touched by the American Beats—by Kerouac’s On the Road, and also by the poetry of Allen Ginsberg and Lawrence Ferlinghetti—and by French symbolists like Paul Verlaine and Arthur Rimbaud. Both Verlaine and Rimbaud are mentioned specifically in the Blood on the Tracks song “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go.”

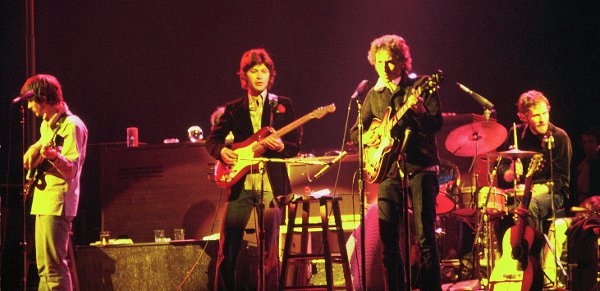

Dylan’s relationship with some of the Beat poets was interesting and obviously deeper than his relationship with the authors he had only read, such as Leo Tolstoy (though their life paths never crossed—Tolstoy died 31 years before Dylan’s birth—Dylan did visit Tolstoy’s estate). With time, Dylan and Allen Ginsberg became friends, and the Basement Tape recordings with The Band led to the humorously titled track, “See You Later, Allen Ginsberg.” Over the years of their friendship, each influenced the other. In the Martin Scorsese Dylan documentary, No Direction Home, Ginsberg claims to have wept the first time he heard “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” (a very poetic track from 1962’s Freewheelin’). The Dylan-Ginsberg relationship is also captured in the 2007 surrealist biopic I’m Not There (with Cate Blanchett playing a Dylan persona and David Cross as Ginsberg).

Aside from his public friendship with Ginsberg, Dylan has also become acquainted and corresponded with Lawrence Ferlinghetti and had composed songs for the poet Archibald MacLeish (though the songs were not used in the failed MacLeish play, but rather for the early ‘70s Dylan album New Morning).

While films like I’m Not There and numerous books and articles on Dylan suggest that he is a man with many masks, it is perhaps a line from a letter written by Rimbaud that defines him best: “Je est un autre.” Music and cultural critic Ellen Willis writes, “Not since Rimbaud said “I is another” has an artist been so obsessed with escaping identity. His masks hidden by other masks. . . .” This point was made also by music historian Greil Marcus and by Todd Haynes and Oren Moverman in their screenplay for the film I’m Not There. While Dylan denies in his memoirs that he is a man of many masks, he writes near the end, “When I read [Rimbaud’s] words the bells went off.”

We are all always changing, and, for many of us, our tastes change along with our influences and beliefs. Dylan is no exception, though the public eye would have us believe that he changes more often than most (perhaps he does) and is rife with contradictions (perhaps he is). Dylan is notorious for saying one thing in one interview and saying the seemingly opposite in another. But can’t the same also be applied to many celebrities who live out the bulk of their lives in front of cameras and audiences?

In terms of literary influences, Dylan has, at times, referenced and shown appreciation and even admiration for certain writers, and has at other times spoken of the same writers distastefully. For instance, in a 1965 interview with Paul J. Robbins, Dylan says of T.S. Eliot: “You read Robert Frost’s “The Two Roads,” you read T.S. Eliot – you read all that bullshit and that’s just bad, man, it’s not good. It’s not anything hard, it’s just soft-boiled egg shit.”

That same year Dylan referenced Eliot in the long, strange track “Desolation Row,” from Highway 61 Revisited, a number filled with a circus sideshow of characters, from Cinderella and Quasimodo to Pound, Eliot and Dr. Filth. In that piece Dylan sings, “And Ezra Pound and T.S. Eliot, fighting in the captain’s towers/while calypso singers laugh at them and fishermen hold flowers.” While this doesn’t necessarily suggest any disdain for Pound or Eliot, some have interpreted it as a criticism. In response to these lyrics Archibald MacLeish asked Dylan (as explained in Chronicles), “Pound and Eliot were too scholastic, weren’t they? . . . I knew them both. Hard men. . . . I know what you mean when you say they are fighting in a captain’s tower.” In that same paragraph, Dylan admits of Pound, “What I know of Pound is that he was a Nazi sympathizer in World War II and did anti-American broadcasts from Italy. I never did read him.” As for Eliot: “I liked T.S. Eliot. He was worth reading.”

James Joyce is another interesting literary figure in the world of Dylan. He explains in Chronicles that “James Joyce seemed like the most arrogant man who ever lived, had both his eyes wide open and great faculty of speech, but what he say, I knew not what.” Many readers—or attempted readers—of Finnegan’s Wake would likely agree. Joyce comes up again, five years later, in Dylan’s 2009 album Together Through Life, in the track “I Feel a Change Comin’ On”: “I’m listening to Billy Joe Shaver/And I’m reading James Joyce.” Of course, as with Eliot, one can read Joyce and still find his writing impenetrable and still find him to be an arrogant, yet brilliant genius. And, besides that, despite Dylan’s admission over the years that many of his songs are deeply personal (most recently in his latest Rolling Stone interview), there is no reason to surmise that any song is actually about Dylan himself, and is not merely being sung in character (just as Nicki Minaj, in character, recently voiced support for Mitt Romney as president).

Another who Dylan has dealt with ambiguously over the years is the poet Dylan Thomas. In many early career interviews (such as his 1978 interview with Playboy magazine), Dylan repeatedly denied taking his stage name from the poet. In Chronicles, however, Dylan explains that he was initially planning on changing his name to Robert Allyn, but upon discovering some poems by Thomas, he felt that Dylan had a stronger feel, and thereupon settled on changing his name from Bobby Zimmerman to Bob Dylan. It’s possible that Dylan’s memory of the events changed over the years, but it is also possible that Dylan substituted one public mask for another by 2004. While it’s always fun to speculate, it doesn’t really matter one way or the other.

Other literary figures whose works have popped up in the landscape of Dylan’s music over the years have been varied, including Lewis Carroll (“Tweedle Dee and Tweedle Dum”), Anton Chekhov (Blood on the Tracks), Arthur Conan Doyle (“Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues”), F. Scott Fitzgerald (“Ballad of a Thin Man” and “Summer Days”), the Brothers Grimm (Highway 61 Revisited and “Sara”), Victor Hugo (“Desolation Row”), Herman Melville (“Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” and “Lo and Behold!”), Friedrich Nietzsche and Wilhelm Reich (“Joey”), Junichi Saga (quoted often on Modern Times) and John Greenleaf Whittier (“Scarlet Town”). Of course, this is only a miniature sampling of some of the more direct references made over the course of the prolific and intricate fifty year career of rock and roll’s poet laureate.

In Chronicles, Dylan opens up more about the writers that shaped his ideas over the years, from Enlightenment-era thinkers like Voltaire, Rousseau, Locke and Montesquieu, to Modernists like Eliot, Fitzgerald and Faulkner (whom Dylan says he “didn’t quite get”), and to Beat writers like Kerouac, Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti and Gregory Corso. Dylan’s literary influences actually stretch all across the spectrum, including writers from many diverse literary movements. There were the romantics like Victor Hugo, the realists like Honoré de Balzac (whom Dylan finds “hilarious”), theorists like Nietzsche, Marx and Clausewitz, and the classic Greek and Roman writers like Thucydides, Sophocles and Ovid. Of course, it was poetry most of all that moved Dylan. Ellen Willis writes that “[Dylan] had less in common with the left than with literary rebels—Blake, Whitman, Rimbaud, Crane, Ginsberg”—mostly poets—and later describes Dylan as a man whose admirers look at him as “a poet using rock-and-roll to spread his art.”

All of the literary rebels that Willis mentioned in her article (written between 1967 and 1968) resurface in Chronicles, along with a long list of other poets, including: Byron, Shelley, Longfellow, Milton, Coleridge, Shakespeare, Villon, Poe, and the French Symbolists and American Beats. He was also moved greatly by short stories, and in Chronicles he mentions storytellers such as Jules Verne, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Luke Short and H.G. Wells. Dylan is both a poet and a storyteller in his own ways, so this certainly seems fitting, and he describes his allure to folk music (in his memoirs) to the fact that folksingers could “sing songs like an entire book, but only in a few verses.” In other words, folksingers were concise storytellers.

Chronicles is filled with gems that allow music historians a glimpse into the portrait of Dylan, the artist, as a young man, and of the cultural patchwork that made up the world of his songs and writing. But one can also learn a great deal about Dylan’s literary influences from interviews and liner notes to albums. In the 1978 Playboy interview with Ron Rosenbaum, for instance, Dylan cites Chekhov as his favorite writer, and Henry Miller as “the greatest American writer.” Liner notes to albums like Freewheelin’, Bringing It All Back Home, Planet Waves and Desire make references to authors like Ginsberg, Hugo, and Tolstoy, among others. The interviews published within the delightful three-disc box set, Biograph, are also very illuminating, in which Dylan mentions the likes of William Burroughs, e.e. cummings, and Albert Camus. And in his earlier stream of consciousness book, Tarantula, Dylan lists a string of writers, including Kafka, Hemingway and James Baldwin. Many of the same writers Dylan references in his songs and his written works also reappear on his Theme Time Radio Hour program, such as Tennessee Williams, whom Dylan refers to as his “favorite playwright.”

Of course, of all of the writers, texts and literary characters incorporated into the weird and wonderful world of Dylan’s music, the Bible has assumed the most prominent role, as it does in the works of many artists in the Western cannon. Tempest, despite being a phenomenal album, was not what Dylan initially had in mind for his 35th studio recording. According to his recent Rolling Stone interview, he wanted to make another religious album, but explains, “That takes a lot more concentration . . . than it does with a record like I ended up with. . . .”

Dylan has been quoting and referencing scripture long before his so-called gospel period in the late-1970s and early-1980s (when he released albums like Slow Train Coming and Saved). Religion was an important part of both the folk and blues traditions, each of which contributed to his artistic style. References to Jesus, the Garden of Eden, Abraham, Goliath and a cornucopia of biblical stories have been abundant in his songs over the years, more so on some albums than others. Buddha has also popped up in some songs (“Precious Angel” and “Hurricane”). The use of biblical or religious imagery is no less true with any of his later music than his early or mid-career recordings. Though Tempest was not the religious album that Dylan initially wanted to make, religious references can still be found, such as in the opening track, “Duquesne Whistle,” which includes the lines, “I can hear a sweet voice steadily calling/Must be the mother of our Lord.”

Religious texts, collections of poetry, novels and stories have all played significant roles in the life and works of Bob Dylan, shaping the artist’s music and writing, which would later influence so many others. In his early years, in particular, Dylan was—like many young artists and intellectuals—a sponge, absorbing the knowledge and culture that would help fuel his creative genius for more than half a century. As Dylan reflects in Chronicles, “I was looking for the part of my education that I never got.” It seems that he got enough of it over the years, through folk stories, history, music, art, film, literature and life experiences to help him create new songs for at least another 50 years. As Rolling Stone music critic Will Hermes correctly observes about Dylan’s newest album, “Lyrically, Dylan is at the top of his game.”

Try though we may, it isn’t really possible to pinpoint all of the literary influences of any one artist, especially when that artist is Bob Dylan. Yet, we can still make some damn good educated attempts. As Dylan writes in Chronicles, experience, imagination and observation set the train of creativity into motion, and literary influences are only one small (though important part) of Dylan’s creativity. Life experiences, painters, (like Goya, Boticelli and Picasso), films (like La Dolce Vita and La Strada), radio shows, musicians (ranging from Guthrie, Johnson, Leadbelly, Blind Willie McTell, and Big Bill Broonzy to Elvis, Buddy Holly, Hank Snow and Hank Williams and even to Neil Young and Alicia Keys) and all sorts of other things have undoubtedly played a role in Dylan’s creative consciousness. Often, as noted by music historians like Greil Marcus (in his book The Old, Weird America), and by Dylan himself, Dylan has drawn on the American past, on our country’s rich and strange history to create a world that transcends our immediate present.

Bob Dylan was only 20 years old when his first, eponymously-titled album was released, though he may as well have been 60. Now he’s 71. Over the course of his career, Dylan has been, among other things, a folk singer, a poet, a rock star, an artist, a family man, an evangelist, a myth, a part of America’s collective consciousness. He drew on the rich past of both this country and of the world (and continues to draw on it) – its history, its literature, its art, its music – and has created a mixed-up world of songs, characters, and ideas that have become both part of America’s present and something beyond it. The strange world of Dylan’s music is the world of “Desolation Row,” where Pound and Eliot duke it out in the captain’s tower, but it’s also the world of Quasimodo and Bessie Smith, of Harry Smith and the sinking of the Titanic, of Brigitte Bardot and Medgar Evers, of Poe’s raven and of Bear Mountain picnics, in short a kaleidoscopic hodgepodge of elements from this muddled up, truth-seeking, topsy-turvy world that we all pass through on our journeys of life.

Author Bio:

Benjamin Wright is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

Photos: Stuart Hampton, Jim Summaria (Wikipedia Commons).