The Life and Death of David Foster Wallace

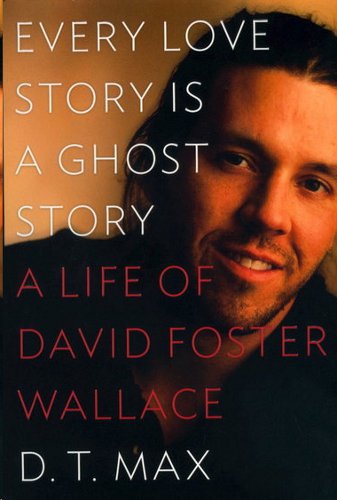

Every Love Story is a Ghost Story: A Life of David Foster Wallace

By D.T. Max

Viking

356 pages

In his short story, “The Depressed Person,” David Foster Wallace described a young woman “in terrible and unceasing emotional pain” who understands that “the impossibility of sharing or articulating this pain was in itself a component of the pain and a contributing factor in its essential horror.” The depressed person has a core group of friends scattered around the country that she calls her Support System, rotating between them for long-distance calls in the middle of the night when her pain is most acute. The problem is, she tells her therapist, these calls don’t necessarily improve her condition:

“The depressed person confessed that when whatever empathetic friend she was sharing with finally confessed that she (i.e., the friend) was dreadfully sorry but there was no helping it she absolutely had to get off the telephone, and had finally detached the depressed person’s needy fingers from her pant cuff and gotten off the telephone and back to her full, vibrant long-distance life, the depressed person almost always sat there listening to the empty apian drone of the dial tone and feeling even more isolated and inadequate and contemptible than she had before she’d called.”

It’s not necessary to read too closely into stories like these to determine facts of Wallace’s life experience and throughout the biography, literary journalist D. T. Max is astute in his selection of relevant quotations. But anyone who could write “the depressed person … felt able to share only painful circumstances and historical insights about her depression and its etiology and texture and numerous symptoms instead of feeling truly able to communicate and articulate and express the depression’s terrible unceasing agony itself, an agony that was the overriding and unendurable reality of her every black minute on earth” knew what he was talking about. Wallace struggled with depression during most of his adult life, which he chose to bring to an end on September 12, 2008—cutting short the career of what was by critical consensus one of the rare geniuses in contemporary American literature.

In Every Love Story is a Ghost Story, a sympathetic and engrossing biography of David Foster Wallace, Max deftly outlines the early years of the writer's life, from his birth in Ithaca, New York, growing up in Champaign, Illinois, where he became a promising junior tennis player, to his education (with a double major in English and philosophy) at Amherst College. The novel he wrote for his senior thesis, The Broom of the System, was published when Wallace was 25 years old, launching a career that went on to see creation of a range of exceptional works of fiction and nonfiction—most notably, a 1,079-page novel, Infinite Jest (1996) that propelled him into the first rank of American authors. Fame was a place that he was emotionally ill-equipped to handle, particularly since writing about the psychic effects of our information- and media-saturated age was among his foremost concerns.

D.T. Max notes the ponderous irony of Wallace’s bewilderment when obliged to promote Infinite Jest at bookstores, through magazine interviews and, most baffling of all, on Charlie Rose’s public television talk show: “ … the encounter was uncomfortable, as Wallace rocked back and forth in his white bandana, battling the urge to spew out the churning contents of his mind—to be on TV talking about TV left him particularly confused.” Wallace’s fiction (and some of his groundbreaking nonfiction) was all about how mass media had damaged an entire generation’s psyche; to willingly participate in this media frenzy exacted a terrific toll on his already fragile personality.

Spewing out “the churning contents of his mind” was to a great degree what set Wallace apart from other novelists in the late 1980s and 1990s. Readers and critics hadn’t seen such an explosion of maximalist prose in years, complete with page upon page of single-spaced footnotes, all in pursuit of an accurate depiction of our overheated mental and emotional daily lives. (The same approach was employed to stunning success in several nonfiction pieces written during this time. Many of us who deeply admire Wallace consider his essay on visiting the Illinois State Fair, “Getting Away from Already Being Pretty Much Away from It All,” and his heart-rending account of life aboard a cruise ship, “A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again,” to be among his finest works.) That Wallace bent this technique to explore the effects of substance addiction and the tortured relationships between men and women, and then sought to move beyond what he considered an easy irony to something of life-affirming sincerity, are hallmarks of his achievement, deepening his tragic conclusion that he could no longer continue moving forward.

Infinite Jest appeared when the Internet was on the cusp of exploding, and eventually taking over our lives. Wallace’s complex and fractured narratives precisely anticipated its jangling effects. As Max notes:

“Beset by anxiety and whipped by consciousness, his was a mind more drawn to the flat bright outlines of personhood than the nebulous contours of personality; it would be too simple to say that life for Wallace looked even more like the Internet than it did for television, but there is truth to it … As the culture collapsed into the anecdote and sound bite, Infinite Jest was one of the few books that seemed to anticipate the change and even prepare the reader for it. It suggested that literary sense might emerge from the coming cultural shifts, possibly even meanings too diffused to see before.”

Max recounts the many ups and downs in Wallace’s life and career with admirable restraint and compassion (after decades of tempestuous relationships, he found relative peace in a marriage to the artist Karen Green and a teaching position at Pomona College), while remaining sensitive to the writer’s ever-roiling interior life. The life of David Foster Wallace was marked by alternating periods of wondrous creativity and bottomless emotional turmoil. While not examining all of his works in the detail they deserve, D.T. Max has nonetheless produced a biography worthy of its complex and greatly missed subject.

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi is chief book critic for Highbrow Magazine.

Photos: Steve Rhodes (Flickr, Creative Commons); Viking Press.