Sue Coe’s Combustible Art Takes on Donald Trump

Sue Coe is a true Cassandra for our times. But unlike the proverbial canary in the coal mine, she is no victim. She has willingly put herself in the thick of the swamp since the 1980s and through the alchemy of her social protest art, emerged if not triumphant, a prophet we cannot afford to ignore.

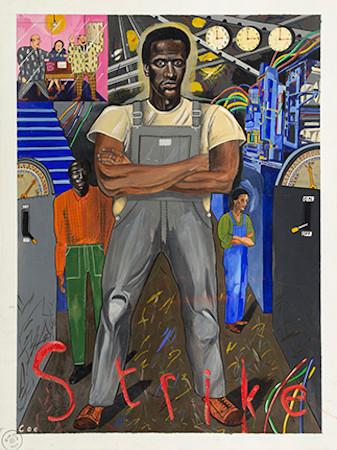

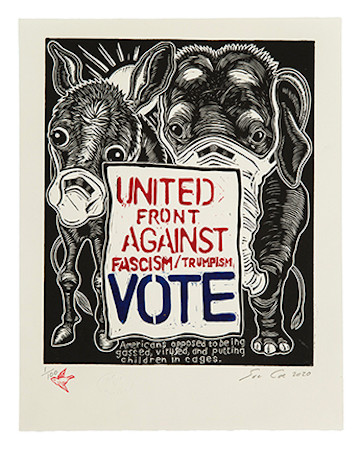

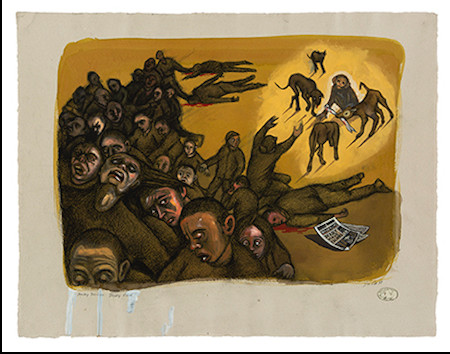

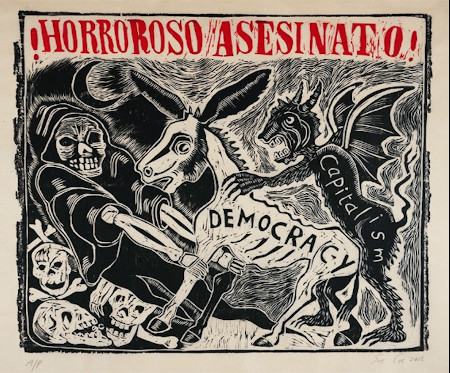

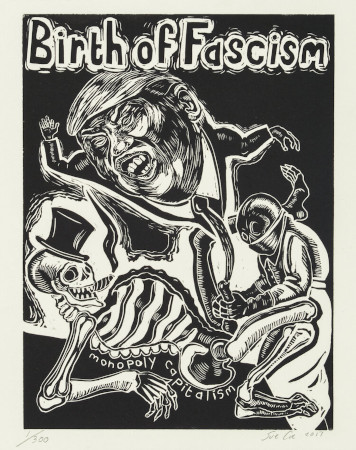

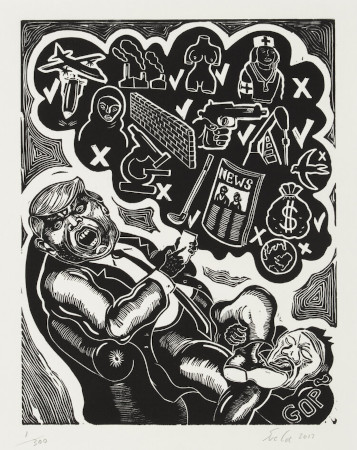

The current exhibition of her works at GSE, Galerie St. Etienne in New York City, “It Can Happen Here”, is available in its entirety online, with an essay that not only introduces the reader to her political obsessions but provides a historical overlay of the ills of a society that has so often put profits above individual lives. In her scathing linocuts and graphite depictions, she has tackled it all—systemic racism, income inequalities, the lack of healthcare, global warming, police brutality, a rising and insidious fascism, the ravages of plagues, from AIDS to the COVID virus, and—Donald Trump.

Born in Staffordshire, England, in 1951 to blue-collar parents, she was able to take advantage of free higher education available through the Labour Party. On a scholarship, she trained as an illustrator at the Royal College of Art. While there, It might have been two American sisters she met who brought her to New York—--“they wore no makeup and had long wild hair, they were like aliens, they were so…I wanted to go to that planet where they came from.” Arriving in 1972 with $100 in her pocket, she went straight to the New York Times, which gave her an illustration job on the spot. The rest is history, as they say.

A laser-sharp political awareness doesn’t flourish in a vacuum and studying at the Workshop for People’s Art had exposed her to the poster art and library sources that fueled her imagination. If the likes of Rembrandt, Goya, and Kathe Kollwitz filled her nascent eyes, expressionist Otto Dix and social muralist Jose Clemente Orozco heightened it further. She visited prisons, AIDS wards, even slaughterhouses to peel the layers of her vision clean. Although studying the results, I question whether she ever greeted the world with rose-colored glasses.

One of the earliest works that made her reputation in the East Village art scene is How to Commit Suicide in South Africa (1983). Critic Donald Kuspit hailed her as “the greatest living practitioner of a confrontational, revolutionary art.” South African apartheid was a worthy subject, but she couldn’t ignore the Anglo-American politics of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan. She had witnessed police brutality in London as well as here, and her 1986 painting Traffic Violation shows officers beating a man for “driving while black.” Her Police State (1986) is another example of burgeoning abuses of power in the name of law and order. We Are All in the Same Boat, a stark hand-colored woodcut from (2005) is also an oft-used expression of the artist.

Wood carving as an art form has been long established but often overlooked in its ability to evoke strong emotional responses in the viewer. Notable practitioners in recent history include Frans Masereel, a Belgian active in anti-war movements during World War I, put urban corruption in high relief with his graphic novel, The City. Another contemporary who excelled in the art was the great German painter Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, whose experiments brought the form to a new level. For Coe, “Carving strips away what was lovely about my drawings, all those intricate tones, down to raw content. It removes my pride in clinging to technique, down to the urgency of what needs to be said. It matches my rage, slashing away at the wood or linoleum and seeing the chips fall.”

The tragic prevalence of the coronavirus on everyone’s mind is understandable, but Coe’s awareness of plagues as subject matter is almost eerily prescient. In 1997 she produced Deadly Virus (Monkey Business) followed by her 2004 series Fowl Plague, documenting how one such pathogen jumped from chickens to a Vietnam populace.

Doctor MAGA (2020) is a brilliant depiction of Trump in the guise of a medieval plague doctor. Another, The Dim Reaper (2020) shows him egging on practices that help spread the virus. Coe explained that her relief printing—linocut and woodcut—was perfect for her Trump and COVID work because the ancient technique is well-suited to digital reproduction. I might add, ideal for the increase in viewers she consistently attracts.

There are other examples of her satirical, lacerating treatment of Trump, one even depicting his misogynistic treatment of women. Unpresidented (2017) shows Trump attacking the Statue of Liberty, grabbing lasciviously at the folds of her skirt. The metaphor is perfectly clear.

The title of the exhibition takes its genesis from Sinclair Lewis’s 1935 novel, It Can’t Happen Here. Written while the world was in the throes of the Great Depression and Hitler’s rise, the novel describes the rise of a American fascist. Coe’s linocut It Can Happen Here (Trump) (2016) in the fall of 2016 depicts Trump tearing up the U.S. Constitution. Hillary Clinton was widely believed to be the winner then but once again, Coe’s unnerving talents as an oracle tell the real story.

Some may call her a revolutionary, others a humanitarian, and still others--especially those who are familiar with the profound influence of her art--a national treasure. Coe’s exhibitions, awards and publications are too numerous to mention. A few: Coe was elected into the National Academy of Design in 1993. Sheep of Fools, Coe's collaboration with Judy Brody, was Nonfiction Book of the Year in 2005. She was awarded the 2015 Lifetime Achievement in the Visual Arts award from Women's Caucus for Art, for her dedication to art and activism.

New York Times columnist Frank Bruni, in the wake of the current presidency, wrote “I can’t look at America the same way.” Sue Coe makes sure we don’t look away.

(Founded in 1939 by Otto Kallir (1894-1978), the Galerie St. Etienne is the oldest gallery in the United States specializing in Austrian and German Expressionism. It has mounted the first American one-person shows of such artists as Erich Heckel (1955), Gustav Klimt (1959), Oskar Kokoschka (1940), Paula Modersohn-Becker (1958) and Egon Schiele (1941). The gallery is also known for its expertise on Käthe Kollwitz. The current director, Jane Kallir, has written over 20 books and is the leading authority on Egon Schiele.)

For Highbrow Magazine

Image Source:

All images courtesy of the artist and Galerie St. Etienne