The Master of Reinvention: Why Woody Allen Still Matters

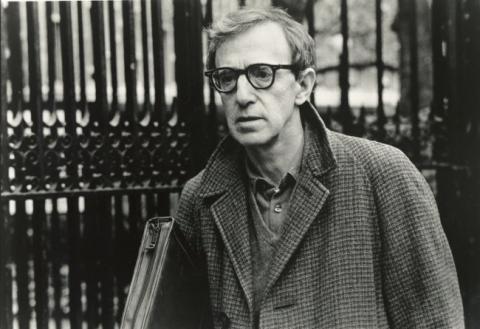

Woody Allen’s films — 40 in all, from 1971’s Bananas to 2011’s Midnight in Paris — compose one of the most astonishing sequences of cinematic expression in American movie history. For a filmmaker who is often accused of making the same picture over and over, Allen is remarkably adept at reinvention. Who expected Interiors after Annie Hall? Or Zelig after A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy? Or Match Point after Melinda and Melinda?

Allen uses the tunnel-vision approach to moviemaking: He often begins writing the script for his next film on the very day he finishes editing his previous picture. This method allows him to steadily and unceremoniously produce a movie every year. At such a breakneck speed, not every film is a masterpiece, but nearly a fourth of them are — a testament to his singular achievement as a humorist, satirist, filmmaker and performer.

The classic Woody Allen works of the 1970s (Sleeper, Love and Death, Annie Hall, Manhattan) have been given their due, but a second golden age in his filmography runs from 1992’s Husbands and Wives to his sadly undervalued 2001 entry, Curse of the Jade Scorpion. This 10-film streak represents his finest efforts as an actor-writer-director because it offers his most successful experiments with the two seemingly opposed aspects of life that have obsessed him for decades: comedy and tragedy. “That’s what I’ve been fooling around with for a while now,” Allen told interviewer Stig Björkman in Woody Allen on Woody Allen. “The attempt to try and make comedies that have a serious or tragic dimension to them. And this is not so easy for me…because it’s very hard to strike a balance in a story so that it’s amusing and also…tragic or pathetic. It calls for a lot of skill to do that; one tries and one is afraid of failing and then sometimes one gets lucky and accomplishes it.”

His movies rest upon the belief that life is essentially a comedy. If life is a tragedy, there’s little reason for laughing: see Match Point and the dramatic half of Melinda and Melinda. Life is comic, but it is also tragic. That’s why Allen’s best comedies ask big questions. Small Time Crooks is, on one level, an examination of how sudden wealth affects several low-class thieves. Superficially, Curse of the Jade Scorpion is a 1940s comic-book detective story -- an absurd screwball romance with snappy dialogue. But it’s also unmistakably about the shock one experiences upon recognizing the truth of reality. The magician in Jade Scorpion offers this prophetic warning: “The ugly curtain of reality will soon fall upon us.” Allen told Björkman, “You can really see my personality come through on that line. The truth is that we don’t live in a hypnotic trance all the time, where we see things beautifully. The truth is that reality comes back, and it’s not so pleasant.” In Small Time Crooks and Jade Scorpion, a farcical plot is subtly given dramatic weight.

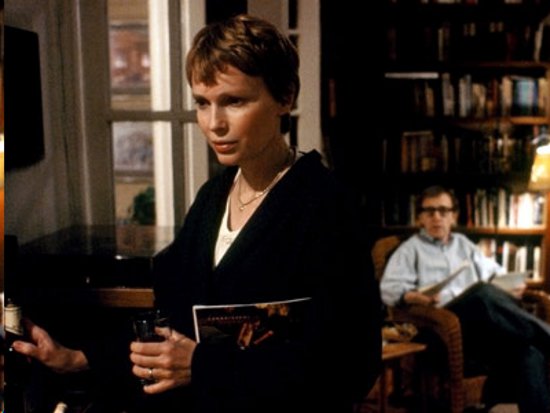

Husbands and Wives is quite the opposite: A tragic plot is given a comic coloring. During filming, Allen devised a new visual composition. It began with the disappointing discovery that movies look too neat and polished. “So much time is wasted [on] the prettiness of films and the delicacy and the precision,” he told Björkman. “And I said to myself, why not just start to make some films where only the content is important. Pick up the camera, forget about the dolly, just hand-hold the thing and get what you can….Don’t worry about all this precision stuff and just see what happens.” Husbands and Wives, an uncomfortably dark mockumentary about two middle-aged couples drifting apart, is, as Allen says, “more volatile and explosive” than his previous films. (The choppy, jump-cut editing further enhances the anxiety.)

The following year, in Manhattan Murder Mystery, he used the same filmmaking technique to craft a grounded farce that is menacing and devastatingly suspenseful; the final effect has an improvised, off-the-cuff quality. This freewheeling approach allowed for even more impressive performances. Sean Penn was interviewed in Robert B. Weide’s engaging 2011 film Woody Allen: A Documentary about working with Allen as a director. “His feeling is that the best, complete thing he’s gonna get is going to come out of the actor’s instinct,” Penn said. “What he finds out on the first day is whether or not he cast it well.”

Allen’s casting process has always been notoriously mysterious. And during this period he made even bolder casting choices, each of which paid off enormously well onscreen. Douglas McGrath, his screenwriting partner on Bullets Over Broadway, thought Dianne Wiest was the worst choice for the self-absorbed stage diva Helen Sinclair. Wiest even thought she was wrong for the part until Allen convinced her otherwise. Sydney Pollack is flawlessly cast in Husbands and Wives; Tracey Ullman is ideal as Allen’s insufferable wife in Small Time Crooks; and Kenneth Branagh’s rendition of the Woody Allen persona in the criminally underrated Celebrity is a revelation. Curiously, it was Branagh’s performance that was attacked by the critics. In his review of the film on November 20, 1998, Roger Ebert complained Branagh “does Allen so carefully, indeed, that you wonder why Allen didn’t just play the character himself.” Allen has played himself many times before. He explained to Björkman that it’s puzzling to him that some people seemed to be “searching for a reason why they didn’t like [Celebrity]. And they thought that I should have played the part, instead of Kenneth trying to play me. But I would always answer that Kenneth is doing me better than I ever could have done me.” It’s difficult to challenge Allen on this point: Branagh — young, handsome, neurotic, over-anxious, girl-shy — does play the Allen character better than Allen; he adds a dashing charm to the character that would have otherwise been absent.

Bullets Over Broadway is considered Allen’s best all-out farce, but Manhattan Murder Mystery is arguably his crowning achievement. It’s probably as close as Allen will come to making a horror movie — the scenes are infused with an explosive mixture of farce and danger. He uses the camera like Stankley Kubrick or Roman Polanski — spinning and lurking and trailing and eavesdropping and freely framing the scenes as they unfold.

When Allen was writing Annie Hall with Marshall Brickman, they originally outlined the film as a murder mystery. The idea was abandoned for nearly 15 years and Annie Hall went on to become something completely different in the editing room. But Manhattan Murder Mystery (co-written by Brickman) works as an imaginative sequel to Annie Hall. It’s as if Alvy and Annie did get back together and got married and grew into a a couple of typical Manhattanites. They’ve changed their names: Alvy is now Larry and Annie has become Carol. He drags her to hockey games; she drags him to a Wagner opera. And one night they bump into an old couple down the hall and are almost bullied into stopping by for coffee. When the better half of the couple suddenly drops dead, Carol (the superb Diane Keaton) suspects the husband killed her, and Larry suspects his wife has gone crazy.

Manhattan Murder Mystery has a deeper dimension beyond the murder mystery of the title. The mystery is a symbolic scenario used to explore the notion that a marriage without adventure is a marriage worth reexamination. Carol says “Larry, I think it’s time we re-evaluated our lives.” He responds “I’ve reevaluated our lives: I got a 10, you got a 6.” The movie isn’t about the murder as much as Carol and Larry’s marriage.

When Larry is holding a copy of Marcia’s manuscript in his office, we catch a glimpse of the title in capital letters: “COMFORT ZONE.” It’s never mentioned, but perhaps it’s there for a subtle reason. The whole movie is about Woody Allen being pushed outside of his own comfort zone. This is one of his best performances onscreen. He’s quite understated until mind-boggling circumstances push him — the timid and feverishly nervous and multi-phobic personality that he is — into behavior that is at once completely believable and utterly slapstick. The film suggests that love requires growth, and growth requires courage, of which Woody Allen has plenty as a filmmaker.

During the past decade, Allen has produced a curiously inconsistent mélange of critical and commercial flops. Match Point, an enticing Dostoyevskian exercise, and the charming romantic comedy Vicky Cristina Barcelona are obvious exceptions. Hollywood Ending offers a few situational laughs and portions of Melinda and Melinda are undeniably clever, but Anything Else, Scoop, Cassandra’s Dream and Whatever Works are the efforts of an inventive filmmaker struggling to find something fresh to film. After the meandering You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger, Allen found his footing once again with last year’s lighthearted comic fantasy Midnight in Paris. With his next film — To Rome with Love, a modern re-imagining of Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron — scheduled for a summer release, one thing remains apparent: The Woody Allen audiences adore is back.

Author Bio:

Christopher Karr, a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine, is originally from Barbourville, Kentucky. After graduating from Northern Kentucky University with a BFA in Theatre, he co-founded the experimental theatre group Artemis Exchange. Since moving to New York City in 2008, Karr has written a novel, poetry, essays, a slim adaptation of the Bible, and an unfilmable screenplay based on Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle. His award-winning plays have been performed in Cincinnati and Chicago.