New York’s Central Park Pays Homage to the Suffrage Movement

Women’s right to vote—it’s been a long time coming. Even though Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Sojourner Truth didn’t live to see the passage of the 19th Amendment on August 18, 1920, they put up a great fight. And the long overdue Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument, a 14-foot bronze statue unveiled on August 26th, 2020, in Central Park’s Literary Walk, is a permanent testament to their courage.

In sculptor Meredith Bergmann’s words, “I kept thinking of women now, working together in some kitchen on a laptop, trying to change the world.” By choosing to depict three women instead of one, they exist as an allegory of sisterhood and activism. Unlike other solitary male statues on the walkway, “they are not dreaming but working.”

Of course, turning the concept into reality was no easy task. It all started in 2014, when a group of “Monumental Women” volunteers began raising funds for a Central Park suffragist statue. In a New York Times article from August 7, 2020, the group’s president, Pam Elam confessed “Everything about this was not easy.” They could have easily been defeated by the miles of red tape they encountered. Their journey began with the Parks Department, then the Central Park Conservancy, followed by the Public Design Commission, the Landmarks Preservation Commission, and lastly, all the community boards surrounding the park. The sculptor’s design wasn’t selected until 2018, giving her two years, with several creative adjustments, to finish the work.

The original design focused on Anthony and Stanton, with a scroll containing quotations from more than 20 other suffragists. The Design Commission eliminated the scroll, leaving only the two white women. What was missing and what became crucial to its ultimate equal rights message in the wake of growing criticism was Sojourner Truth, the African-American abolitionist and suffragist. By Truth taking her place at the table, the monument was complete. For Bergmann, with less than a year to her deadline, there was no time to waste.

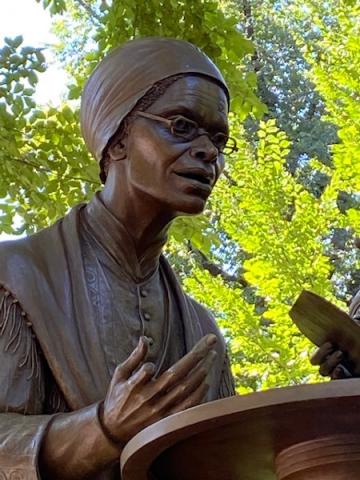

A close-up study reveals the wealth of historical research that Bergmann conducted. Anthony’s cameo around her neck depicts Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom. A sunflower motif in Stanton’s dress signifies the pseudonym Stanton used for herself when she wrote her inflammatory editorials for the Seneca Falls newspaper. It was in that upstate New York town that the first Women’s Rights Convention in the U.S. was held in 1848. Truth’s signature shawl with its tassels and her jacket adorned with laurel wreaths for victory is another perfect choice.

However, the viewer should not look for exactitude in the portraiture. Where Stanton’s poised pen in hand, or Truth’s open mouth and outstretched palm may speak volumes about the discussion underway, the faces are somewhat impassive, giving few clues to the individual personality. Bergmann has said that she tries to come up with “a face that will express more than one moment in the life of this person.” She is no novice to the challenge. As a public works artist, she created the Boston Women’s Memorial in 2003, featuring such luminaries as Abigail Adams and Lucy Stone. Perhaps the result is meant to be larger than a particular subject, that the three suffragists could be interchangeable with the legions of women who took up the good fight.

That said, the sculptor could not have chosen three more charismatic, passionate and diverse personages to be honored. The farther our heroes and heroines fade into the past, the more their characters can blur, becoming more like stone than the flesh and blood individuals they were when they walked among us. A brief summary:

Susan B. Anthony (1820-1906)

Born in Adams, Massachusetts, she was a true champion of temperance, abolition, labor rights, and equal pay. Anthony was, like Stanton and Sojourner Truth, a highly visible leader and speaker, traveling nationwide with her message. Inspired by a Quaker upbringing, equality for all was second nature to her and her seven siblings.

A teacher by trade for many years, she remained single, finally returning to her family home. A meeting with black abolitionist, writer, and statesman Frederick Douglass furthered her passion for ending slavery. Along with Stanton, whom she met in 1851, she cofounded the American Equal Rights Association and became co-editor of their newspaper, The Revolution. By today’s standards, these were women not afraid to make “good trouble” in the words of the late congressman John Lewis. In 1872 she was arrested for attempting to vote. In 1888, after a split among members over black males getting the vote and not women, she helped merge the two largest suffrage associations into one. Every year, she lobbied Congress on behalf of women.

“There never will be complete equality until women themselves help to make laws and elect lawmakers.”

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (1815-1902)

Born in Johnstown, New York. to a father who was a prominent attorney, congressman and slave owner, she was fortunate he had the foresight to teach his daughter the study of law. Exposed to injustices at an early age, her interest in equal rights was soon ignited. She married Henry Brewster Stanton, an impassioned abolitionist and refused the word “obey” placed in her wedding vows. Raising seven children did not deter her from organizing the Seneca Falls Convention and helping to write the Declaration of Sentiments, modeled after the Declaration of Independence. It compared the women’s rights battle against male oppression to the Founding Fathers’ own fight for independence. In later years, she wanted her brain donated to science upon her death to debunk the claims that the mass of a man’s brain made him smarter than a woman’s own. Her children did not, however, comply with her wishes.

“I would have girls regards themselves not as adjectives, but as nouns.”

Sojourner Truth (1797-1883)

Born into slavery in Swartekill, New York, Isabella “Belle” Baumfree escaped with her infant daughter to freedom in 1826. She became the first Black woman to recover her son in a case against a white man. Her life’s journey was a transformative one: Convinced that God had called her to go into the world “testifying the hope that was in her”, she renamed herself Sojourner Truth. In 1851, at the Ohio Women’s Rights Convention, she delivered what became a famous speech during the Civil War period, entitled, “Ain’t I A Woman?” Widely publicized by others in a Southern dialect, it hardly represented a woman who grew up in New York and whose first language was Dutch.

She helped the Union Army recruit black troops and after the war, tried unsuccessfully for seven years to secure land grants from the government for formerly enslaved peoples. Her lectures and preaching drew influential activists to her, including Susan B. Anthony. Today there are countless plaques and statues honoring her selfless efforts on behalf of abolition and women’s rights. The first historical marker was established in Battle Creek, Michigan, and in 1999, on the bicentennial of her birth, a larger-than-life sculpture by Tina Allen was added to Monument Park in the same city. In 2009, a bust of Truth was installed in the U.S. Capitol, making her the first black woman to be honored in the Capitol building. This year, a statue was unveiled at the Walkway Over the Hudson Park in Highland, New York, created by Yonkers sculptor Vinnie Bagwell.

Sojourner Truth on building roads: “If these women (enslaved) are able to perform such tasks, then they should be allowed to vote because surely, voting is easier than building roads.”

As for New York City’s record of the inclusion of women among their monuments, only five depict women, among 150 statues honoring historical figures. In Central Park’s own history, about two dozen men, mostly white, have held the realm. According to the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s inventory from 2011, only 7 percent of nearly 5,200 outdoor statues represent women. Elam’s Monumental Women plans to change all that, challenging municipalities all over the country to include more women and people of color in public spaces.

Now, park visitors who want to glimpse a little bit of female history don’t have to head first to the Alice in Wonderland statue at the miniature sailboat pond, look for Romeo’s Juliet near the Delacorte Theater, or let their eyes scale Bethesda Fountain for the Angel of the Waters. Three suffragists, who actually existed, are waiting.

Postscript: Last Saturday morning, a tribute to Ruth Bader Ginsburg was placed at the foot of the monument.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine