Tragedy of Trayvon Martin Case Represents Harsh Reality for Many Youths of Color in U.S.

From New America Media and Nguoi Viet:

In a darker reality, you would not be reading this. I would not be a writer. Nor would I be a husband to my wife or a father to my new son.

Because if the shaky hands of a police officer had deemed otherwise, my brains would have been splattered all over the backseat of a tan Ford Mustang years ago.

I don’t purport to know all the facts of the admitted recent killing of unarmed Trayvon Martin by George Zimmerman in Sanford, Florida. But I can tell you what it’s like to be a young man of color in a world that too often criminalizes us.

In the summer of 1994, my friends and I were driving to a local basketball gym when our two cars were pulled over by Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputies. My four friends in the lead car were asked to exit the vehicle and put their hands on the hood. I was in the back car with two other friends and we were allowed to stay inside.

Throughout this stop, from beginning to end, the deputies had their guns drawn on us.

I sat in the back right seat. When one of the deputies asked us for identification, I fumbled around inside my duffel bag.

“Don’t mess around in that bag,” the deputy sheriff said. “Or you might get shot.”

But how could I not be nervous? He had the damn barrel of a gun pointed inches from my head!

As I remember back, I can still feel the dominating, almost arrogant presence of that gun. How hot it felt. How it made me cringe. The fear ― of cops and guns ― the moment has permanently instilled in me.

We showed them our identification, both driver’s licenses and college ID cards, and their tone changed quickly. Among the group, we were enrolled in schools like UCLA, UC Irvine, UC Berkeley, the University of Washington, and the University of Pennsylvania, an Ivy League school we readily reminded them.

When they let us go, they told us a spiel we could have recited ourselves: “We matched the description of gang suspects in the area.” Of the seven of us, there were two Japanese guys, two Indian guys, one Filipino guy, one white guy, and me, a Vietnamese guy.

To this day, I still want to meet that gang. At least they practiced diversity, right?

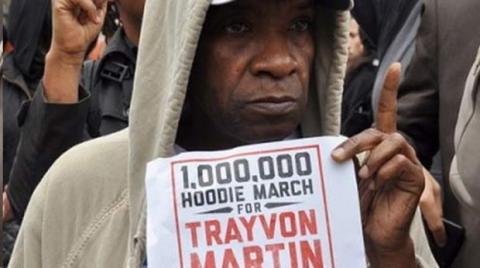

A major part of the discussion of the Trayvon Martin killing seems to revolve around his dress, in particular, a hooded sweatshirt he wore. That particular detail, so common, so trivial, now haunts me.

Because during my encounter with those deputies, I recall that a number of us wore bandanas on our heads. The cops said it was another reason we were pulled over.

But I’ll tell you two things we knew that the cops didn’t. One, we’d grown up in gang turf all our lives and we knew better than to “fly colors.” We always wore bandanas with neutral colors, like white or gray. And two, we didn’t wear bandanas because gangsters did. (Deceased rapper Tupac Shakur, who practically created the look, hadn’t even created his signature bandana style back then).

The irony of getting pulled over by white cops for wearing bandanas? We wore them because we’d seen icons of the 1990s ― cool white guys like Axl Rose, Richard Grieco and Johnny Depp ― wear them. (And they helped to keep the sweat from our bad 90s’ hair out of our faces).

Trayvon’s murder is not an everyday occurrence but it is also not rare. Unfortunately, harassment of young men of color is an everyday reality. I’ve had too many run-ins with the law, where I’ve “met the description,” that it can no longer simply be a coincidence.

If it was tough growing up as an Asian kid in Long Beach, Calif., I can only imagine how terribly difficult it must be to be a Mexican kid in Los Angeles or a black teen in Sanford, Florida.

It’s been almost two decades and that episode has left lasting scars on me as I imagine it has for thousands of youths of color in the United States and frankly, around the world. Of course, I felt embarrassment. You can never erase from your mind the look of disdain from passersby. You are guilty from the first chirp of that siren and the purple glow of blue and red flashing lights.

Then you feel anger, furious at the false accusations and the whole boring repetition ― an urban theater of the absurd ― of it all.

And last, you feel a shunned resentment. Because in those moments, it didn’t matter that we had done what we were supposed to do, that we had worked hard in high school and gone to prestigious universities.

Because in truth, that day those police officers did not see our skin color or our bandanas. They simply saw what they wanted to see.

And that is the great tragedy of the Trayvon Martin murder. That dark skin or a hoodie or sneakers or youth meant Trayvon did not “belong” in that gated suburban community. That the two could not co-exist simultaneously as if they were mutually exclusive factors.

In this dark reality, one that did tragically unfold, black skin and a hoodie meant guilt. A gun meant power. The first now represents a grieving family. The second, as of this writing, a vigilante killer still allowed to roam free.