Joan Miro: The Catalan Magician Remakes the World

Imagine a free-floating black kite, a red balloon weaving its way upwards into an infinite grey space and an enigmatic figure with a white circle for a head holding the balloon’s stringy yellow tail to the ground. You have entered the universe of Joan Miro (1893-1983), and the painting just described is none other than “The Birth of the World.” If it takes a while to get your bearings in this strange landscape, it’s a journey worth the taking, and your suspension of disbelief is highly recommended.

This dazzling exhibition, “Joan Miro: Birth of the World” is not the first time that the Museum of Modern Art has focused on this surrealist Spanish master. MOMA has devoted past exhibits in 1941, 1959, and 1993 (the artist’s centennial year) and such an immersion is understandable considering their extensive holdings. On view are 60 paintings, sculptures, drawings, prints and illustrated books, produced from 1920 to the early 1950s. Anne Umland, the Blanchette Hooker Rockefeller senior curator, with Laura Braverman as curatorial assistant, Department of Painting and Sculpture, have done an exemplary job in helping to elucidate this complicated Catalan genius.

Presented chronologically, there are some real treats for the eye in the early period when the Miro left the comforts of his birthplace at Montroig in 1920 for Paris. He soon became overwhelmed with the Fauvists and their audacious use of color; the Cubists and their assault on the conventions of two-dimensional space; and, particularly, his new Surrealist copains Andre Masson and Yves Tanguy, among others. Inspiration rarely happens in a vacuum and these serendipitous encounters of sensibilities laid the groundwork for the marvelous visions to come.

Miro’s close allies were often the Surrealist poets of the day. The experimental poetry of Robert Desnos, Antonin Artaud and Tristan Tzara, for example, showed him how the pure psychic automatism embraced by these artists and their circle could free him from artistic control. (The exhibit includes several books of Tzara’s poetry illustrated by Miro.)

Miro’s immersion into the prevailing Parisian scene was perfectly timed. Andre Breton’s First Surrealist Manifesto was written in the fall of 1924, and “The Birth of the World” produced in 1925. Predating by decades the “action painting” of Jackson Pollock, the background is a grey morass of pouring, brushing, flinging gestures to signal the explosive nature of creation, acting as the stage on which his floating shapes take their place. Acquired by MOMA as a gift from the artist in 1972, it justifies its place of honor in this show.

Such a work evoked “the void of the infinite”, according to the esteemed critic Waldemar George in 1928. “Miro abandons any discernible equivalence of the world. From now on, he acts in the world of magic.”

How did he do it? In the artist’s own words, from William S. Rubin’s comprehensive 1968 study, Dada and Surrealist Art, “I begin painting and as I paint, the picture begins to assert itself or suggest itself, under my brush. The form becomes a sign for a woman or a bird as I work…the first stage is free, unconscious.” The second stage, however, was “carefully calculated.” A later observation by the renowned art critic Hilton Kramer from the same publication reveals that “surrealism did for Miro what neither Cubism nor any other purely plastic doctrine could have done. It encouraged him to go back to his own childhood for the materials of his mature vision.”

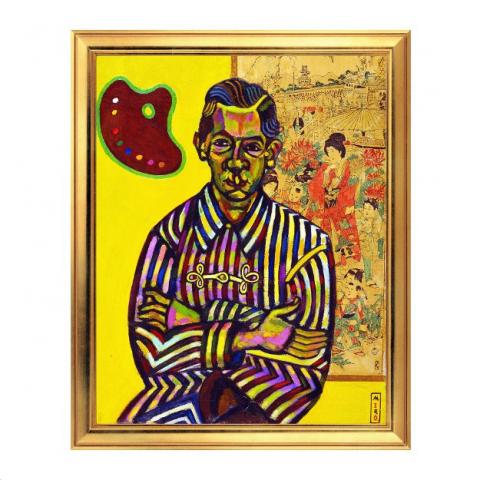

The signs of a fledgling genius of improvisation are evident in his earliest efforts. A highlight of this exhibit is undoubtedly the “Portrait of Enrich Cristofol Ricart”, three years prior to his departure for Paris. One doesn’t have to have the most discerning eye to see influences of Van Gogh and Matisse in this arresting portrait. The artist presents us with a garish yellow background, a Japanese print glued behind his subject, a floating artist’s palette added for good measure, with Ricart decked out in multi-colored striped pajamas. Even his hair is not left to chance, with a repetition of stripes interspersed in his neat black coiffure, giving the whole portrait an almost psychedelic draw.

Interestingly, The Fundacio Joan Miro—a museum dedicated to his works and situated on the hill of Montjuis in Barcelona—contains an evocative portrait of Miro in military garb. Produced in 1916 by Ricart, Miro’s studiomate at the time, it exhibits a similar bold and colorful treatment of its subject. If not evidencing the same inventiveness and wit of Miro’s, it is a strong indication nevertheless of how two painters benefited from each other’s strengths.

Before the artist would abandon the world of formal if disjointed imagery, there are some fine examples of his academic mastery. “The Table (Still Life with Rabbit” (1920-21), one of the few showings on loan from a private collection, presents a Cubist-inspired table, reminiscent of Matisse’s playful perspectives of tables with his signature goldfish. In this case, Miro’s chief subjects are a still-life fish worthy of the finest Renaissance rendering, along with a rabbit and rooster, the latter two very much alive. A clever transition from such efforts is at play in this first gallery, with “Dutch Interior (I)” and “Portrait of Mistress Mills” in 1750 (1928 and 1929 respectively), giving us the bulbous, biomorphic shapes with the wry humor that would distinguish his later signature works.

“The Hunter (Catalan Landscape)” from 1924 is a signature work that acts for the viewer as a kind of roadmap for the black pictographs that would predominate for the rest of his artistic career. Miro doesn’t make his fantastical scene an easy one to interpret—it’s as if he set out to create a crazed cryptogram that only the most intrepid of idiot-savants could comprehend. For the rest of us, comfort can be found in identifying the stick figure in the upper left of the picture—a mustached hunter smoking a pipe, a gun in one hand and a rabbit in the other. The genitals of his subject are there too, in symbolic form, but there’s nothing pornographic here to shock viewers. It’s a masterly puzzle of a serious dreamer.

Another crowd-pleaser is “Hirondelle Amour” (translation: sardine love) at over 6 feet high by 8 feet wide, it’s a jumble of highly contrasted, stylized limbs, hands, and toes in red, black, white and yellow against a midnight blue backdrop. Good luck identifying the sardines!

A darker, more ominous direction became visible in the artist’s work when Miró was forced into exile in France late in 1936 due to his Republican sympathies at home and the onset of World War II. He moved his family to Varengeville, on the coast of Normandy, where he thought they would be safe. There, during a time of great personal anxiety, he began a series of small gouache and oil washes on paper collectively known as “The Constellations.” These works have a sense of immensity, despite their small size. They include “The Escape Ladder” (1940) and “The Beautiful Bird Revealing the Unknown to a Pair of Lovers” (1941), which are featured together in the exhibition. Viewers should note his collage of “Rope and People” during this time, combining coiled rope with grotesque figuration. One could argue that the preservation of his childhood imagery became a survival tactic for the artist.

After the war, his pictographic imagery held sway, bringing Miro to ever-increasing international renown. On exhibit is his Mural Painting (1950-51), 20 feet in length, created as the result of a commission by Harvard University.

How many of the multitudes that stand in awe before his dream landscapes, waiting for the iconic rabbit in the hat to appear or disappear, simply stare in wonder, uncomprehending? Does it matter? Our persistent love of the magician and his magic is precisely because we don’t know how he does it. Miro’s magic is the gift that goes on giving.

“Miro: The Birth of the World” is on view through June 15, 2019 at MoMa.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.

For Highbrow Magazine