The Complex Constructs of Jordan Peele’s ‘Us’

January and February are tough months for movies. They represent the annual dumping ground for all the films that range from the mediocre to the downright terrible. I witnessed the shocking misfire of Stan & Ollie, trudged through the sticky sludge of the charmingly inept Serenity, and cackled in awe at the implausible and amateurish Cold Pursuit.

As February melted into March, there was mild improvement -- at least, there usually is. For all of its bumpy rhythms, and in spite of its flagrant lack of perception about the substance of what composes a romantic comedy, Rebel Wilson brought vibrancy and elegance to Isn’t It Romantic. Fighting with my Family was uneven and oddly old-fashioned and, Dwayne Johnson’s electric appearance notwithstanding, the footage of the real-life family over the end credits immediately gave the impression that a documentary may have been more engrossing. The less said about Alita: Battle Angel the better. Last week, faced with the choice of forgoing the cinema or watching the new bloated, corporatized garbage fire from Marvel Studios, I chose, wisely, to see nothing.

Us, Jordan Peele’s follow-up to his fantastic debut Get Out, was the first movie of 2019 that I genuinely looked forward to, even though the trailer made no sense. The primal pleasures of a movie like Get Out were noticeable from the start. The premise was crisp and clear. You had an immediate sense of the kind of games the movie would be playing. The setup was tantalizing. It also helped enormously that the movie premiered at exactly the right time, capturing the zeitgeist of that flickering moment in 2017 when tensions across the country were perceptibly tightening. And it was legitimately funny. Get Out raked in $255 million at the global box office on a $4.5 million budget and Jordan Peele won a well-deserved Oscar for his original screenplay.

Us is murkier and messier and more ambitious. You could intuit as much from the perplexing extended teaser that gave a splashing glance at the evocative, nightmarish imagery. Indeed, Peele’s focus as a visual storyteller has sharpened. He amplifies the more stunning frames in Us with a pulsating score that signals foreboding, menace, and misery. Even a shot as conceptually simple as a blood-red candy apple dropping into the sand sparks waves of meaning. He stages an agonizingly slow zoom-out of countless rabbits in cages so powerfully and confidently that you feel overwhelmed by the palpable dread of unspoken sadism. He fleshes out minor details with such deliberate calculation that the symbolism of his robust ideas lingers at the surface.

It’s difficult not to notice a chilly shudder that courses through the theater when the young Adelaide (Madison Curry) wins a Michael Jackson T-shirt at a beachside fair. She dons the oversized Thriller shirt as she stumbles into a terrifying situation that changes her life irreparably.

Jordan Peele is drawn to the subtle worminess and unnerving flipside of society. He’s a filmmaker who’s attracted to deep ideas and dramatized diagnoses of our culture’s inner ills. In Get Out, he presented a lunatic new version of slavery; a slavery of the mind and body; a total takeover of a person’s physical self and soul, brilliantly dramatized with those breathtaking, panic-inducing freefall moments in the Sunken Place. The film emphatically illustrated that the protagonist’s deepest, most repressed fears were more valid than he could have ever imagined. The implied coda seemed to be that slavery had not ended -- it just got worse; it went underground; it became loonier and more bloodthirsty. Chris narrowly avoided fate at the end of that picture, but the legacy of mind and body control wasn’t so easily thwarted. He was one of the few who survived.

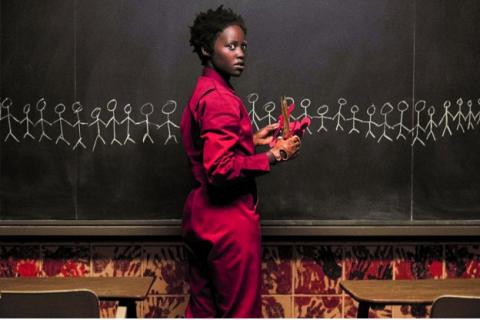

Us takes a more literal approach to more profound concerns. A delicate dance is required to avoid spoilers, so let’s stick to what we know from the trailer. Adelaide, played by Oscar-winner Lupita Nyong’o (12 Years a Slave, Black Panther), goes on a vacation to Santa Cruz with her husband, Gabe (Winston Duke), her daughter, Zora (Shahadi Wright Joseph), and her son, Jason (Evan Alex). Their vacation is violently interrupted by a home invasion by what appears to be devious doppelgängers of the family. Terror ensues, blood is shed, mysteries are manifested, and probing questions about the duality of the main characters -- avatars for “us” in the audience -- are lobbed into the air.

The existential queries abound and reverberate, but you might find yourself getting hung up one in particular; a certain question that stems from the dramatic structure of the film: Why Adelaide? Why now? The opening prologue is an elaborate attempt to provide a compelling answer by suggesting that Adelaide is experiencing this freak show as an adult because she experienced a horrifying trauma as a child that she never fully recovered from. The event that turned Adelaide’s life upside down was the result of being in the wrong place at the wrong time because her parents failed to be vigilant, protective guardians. (To be fair, it was 1986; it was a different time.) Adelaide is a Victim with a capital V. She was a victim in childhood, she is a victim as an adult, and terrible tragedies befall victims randomly. Traumatic events have no logical source and they attack indiscriminately.

It’s difficult to contend with this perspective as a worldview, but within the confines of a dramatic narrative, the mind scans for answers. Peele relishes in playing subtle jokes and leaving minuscule clues along the way -- tiny details that leave subconscious stains upon your brainwaves. Recall how Allison Williams’ character separated the “colored” Froot Loops from the white glass of milk after the climax in Get Out. It’s a visual pun devised to make you chortle in retrospect. The same style of puns abound in Us, but I’m not certain how meaningfully they convey insight into the characters’ inner life. Adelaide could have been the victim of an arbitrary gang of social terrorists, like Liv Tyler and Scott Speedman in The Strangers or Keanu Reeves in the underrated Knock Knock, but Peele has more intellectual concerns. He’s drawn toward the Dostoevskian deep dive -- for better or worse.

The results are mixed. The mainline horror in Us comes with a running commentary about its own meaning. There are several hard sells aimed at insinuating that Adelaide is destined to be the subject of this doppelgänger invasion. Complex, cerebral questions are raised. Is every family in every home being viciously attacked by their Shadow counterparts? If not, why are some families targeted over others? Is this outbreak of doppelgängers local or global? Possibilities are presented but, by the end, there are no answers firmly established. As a result, Adelaide, despite Nyong’o’s feverishly intense performance, becomes a cypher in the center of the story. We sympathize for her struggle without empathizing with her situation. As in Get Out, there a few too many tears shed. There’s a dramaturgical problem presented by this stockpiling of always-at-the-surface emotions because they’re essentially contextless. Without a plausible context built into the premise, it’s not unusual to feel more revolted by the helpless rabbits in cages than by the plight of the protagonist.

There is an über-reversal at the end of the picture that forces you to back-flip through the preconceived notions you carried throughout the running time of the film. Without giving away the specifics, suffice it to say that Peele dares us to ask who’s worse: the Shadow version of ourselves or the selves that we think we are, the selves we perhaps pretend to be? Who is the real victim? Who is the real villain? Who murders whom? The fragments of repercussions that ripple within the conclusion strike intellectual spirals of thought without ever quite jangling our nerves or wrenching our hearts to the point where we identify with Adelaide. Rather, the devious twist at the end strongly encourages us to think more deeply about our motivations for feeling one way or the other about her.

By the end of the picture, the story comes into focus. Not the story onscreen, but the allure of the story that Jordan Peele wanted to tell. Clues about the premise that initially inspired the gears to begin turning for him as a filmmaker are apparent from the epitaph, which claims there are thousands of miles of tunnels under the earth. When you consider the revelations that unfold throughout the narrative, you begin to get a glimmer of the enticing premise Peele wanted to explore.

Rather than reflecting on how the orchestration of the plot managed to swindle even the most perceptive viewer, the accumulation of reversals make you wonder if the story of the film was presented coherently, and I’m not entirely convinced that it is. Excellent endings must be equally surprising and inevitable. Classics like Carrie, Rosemary’s Baby, Candyman, The Tenant, and even Get Out satisfy this requirement. They have the effect of making you think, I didn’t see that coming even though I totally should have! The imaginative reach of Us’s world-building evokes a kind of admiration, but the mechanics and structure of the plot leave you with a wispy equation in your mind. You might leave the theatre thinking, Wait, do I solve for X or am I supposed to solve for Y? Remind me what the quadratic equation is again -- I know I can figure this out.

It’s possible that Peele has no intentions of accomplishing what felt to me like he didn’t quite pull off. Maybe the substance of his thesis is to subvert the common, oversimplified assumptions about victimhood. Perhaps he had no desire to place the audience inside the proverbial shoes of his protagonist, but that comes at the cost of our empathy. If I understand the consequences of the final twist, that empathy would have ultimately been misplaced anyway. As a mainstream exploration of the societal underworld, the ideas of the movie are vibrant and timely. Peele wants to goad us into contemplating the anxiety and suffering that goes on underground and out of sight. There’s a mingled strain of bitterness and stifled rage expressed as a response to radical, countrywide injustice. In this hyper-literalized take on the Jekyll and Hyde premise, it’s hard to say who’s at fault and who’s to blame. If anything, the film suggests they’re both opposing sides circling in a death match, slashing at each other with whatever weapons are available.

Us raises troubling philosophical questions about the substance of who we are, what we might be, and the parts of us left behind. It’s a wilder and more explosive movie than Get Out, even though Get Out is superior. There are a number of noticeably misguided choices in Us. Is the mini-arch involving the Tyler family (glorified cameos for Elisabeth Moss and Tim Heidecker) an essential element of the movie or just another symbolic example of mirrored personalities? Why was Nyong’o, in her suspect and actorly interpretation of her shadow, Red, allowed to speak with that breathy, throaty, croaking voice that’s grating and just plain hard on the ears? Why are the doppelgängers so one-dimensionally delineated that their capacity for verbal expression has been shortsightedly denied to them?

These questions posed snags during and after my viewing, and I don’t believe I was the only viewer who, in one way or another, threw up their arms in wearied submission. (At the movie’s midpoint, the mostly full theatre was starkly aglow with the faint lights of disinterested audience members’ smartphones.) And yet, it was refreshing to see a movie that was worth talking about and discussing.

There haven’t been any other movies in the past three months worth re-tracking and reconsidering in your mind. It’s a movie interested in ideas and constructs and metaphysical speculations. As a filmmaker, and as an ideologist, Jordan Peele isn’t satisfied with taking risks. He takes risks on top of risks. You have to admire his idiosyncratic vision because that vision is all his own. It’s not the result of a movie conceived by committee and shrink-wrapped in cheap packaging in order to sell a “brand.” Now more than ever, we need visionary voices and bold imaginations expressed onscreen. Especially in March.

Author Bio:

Christopher Karr is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine