Eugene Delacroix Unbound: Major U.S. Retrospective of the Artist Opens at the Met

True genius is hard to come by. Perhaps only a few individuals in a century possess the talent, ambition, unquenchable curiosity, and determination to astonish not only their contemporaries—Goethe, Byron, Gericault, to name a few in this case—but to dazzle the formidable denizens that followed. A few hardy souls like Van Gogh, Manet, Cezanne, and Picasso took note as well. Eugene Delacroix was his name and the Metropolitan Museum of Art wants to make sure you don’t forget it.

First off, Delacroix was the quintessential Romantic. Born into a well-to-do family in 1798 (his father was a former minister of foreign affairs who died when he was seven) he fortunately came of age after Napoleon’s fall. Orphaned at 16 upon his mother’s death, he found satisfaction in his fascination for the literature of the greats. That obsession, along with a nascent talent for art kept pace with the mental images that flew off the page into his richly illustrative imagination.

Thanks to a companion exhibit from the private collection of Karen B. Cohen, visitors can experience a wealth of preparatory and independent drawings and lithographs that help orient them for the massive exhibit of paintings that follow. A joint project with the Louvre, it’s an exhaustive collection, encompassing more than 150 paintings, drawings, prints and manuscripts. But for those who linger over the gorgeous graphite, watercolor, and pen and ink renderings before entering the main exhibit, it’s worth the time taken. It’s also worth noting that thousands of sheets were only discovered upon his death in 1863, providing invaluable information about his method and facility at draftsmanship. Under the watchful eye of Guerin, an early teacher, he learned to trace, then freehand copy, and lastly, execute his subject from memory.

A not-to-be-missed portion of the exhibit are 17 plates (never before seen in their entirety) for an 1828 publication of Faust by Goethe. It was an early undertaking that elicited this response from the great author himself: “Monsieur Delacroix has surpassed the mental images that I made for myself from the scenes that I wrote.” There are plenty of opportunities in his drawings to study his aptitude for classical form and his lifelong love for the Greco-Roman aesthetic (inspired in no small part by the 400-year-old Greek War of Independence against Ottoman rule that ultimately led to the demise of his Greek sympathizer friend Byron). But true to the Romantic sensibility, he was more inclined to idealize as well as dramatize his subject. Two masterpieces that speak volumes about this subject are “Scenes from the Massacre at Chios” (1824) and “Greece on the Ruins of Missolonghi” (1826). And what a voracious hunger he had to tackle life and death issues. Humans and animals of all stripes were fair game.

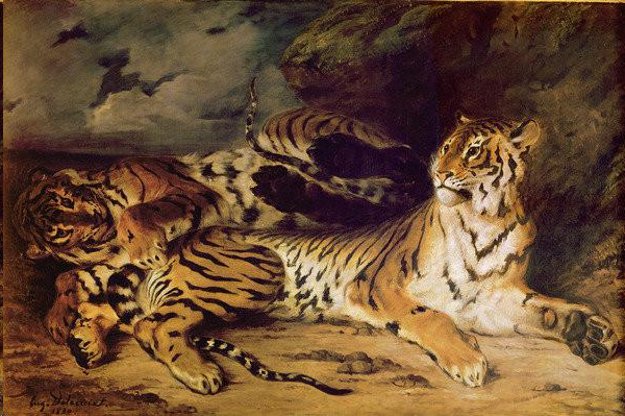

There are crowd-pleasers aplenty for museum and circus goers alike. “Young Tiger Playing with Its Mother (1830) speaks volumes about the breathtaking beauty in animal interaction. The mother at rest exhibits the regality and patience of a queen mother while her cub teases her hindquarters with his paw. The rich brown and black stripes, the whiteness of the cat’s bib and belly, the charcoal in the sky are a sight to behold.

Contrast this with the “Lion Hunt” (1855); influenced heavily by Rubens two centuries earlier, this massive painting was damaged by fire two decades after its completion, leaving the bottom two-thirds intact. Big cats, horses and scimitar-laden Arabs fight for prominence, claws and teeth in abundance. It’s a chilling scene, “all sound and fury” to quote Delacroix’s beloved Shakespeare, but signifying what exactly? Throughout this lavish playground spread over 12 rooms, bravura holds sway, with grandiose themes often overriding their human subjects.

For example, in an 1838 painting of Medea, with dagger poised to murder her children, she is strangely emotionless. The leading character seems totally distracted from the business at hand, looking away from the center of the action. The power in its execution, in the brushwork and composition of the clinging babies in her arms, is evident. Yet something is missing. Most viewers will have a passing acquaintance with this tragic mythical figure and many will be content to accept the scene at hand.

Likewise, “Christ in the Garden of Olives (The Agony in the Garden)” portrays a submissive Christ, holding at bay three distraught angels as witnesses in the background. It’s a gorgeous work, painted with great deliberation, and approached by viewers with a certain reverence. There’s a mystery in the narrative that Delacroix creates in many of his canvases. It’s as if he’s saying this is my version and you will see it my way. A recent laborious effort by the Met to remove layers of old varnish have heightened appreciation of the painting, as much for the play of light and shadow as the familiar subject.

For its calm serenity, brilliance in detail and overall composition, my favorite is “Women of Algiers in their Apartment” (1834). A trio of harem women languor in their room, one in the left foreground, half in shadow, quietly observing us. Two others sit nearby, sharing an intimate conversation, an opium pipe in the foreground along with a discarded slipper. A black servant is about to depart the scene, but hesitates, as if overhearing her mistress. The rich colors of carpet and costumes alike, combined with a partially open red door in the background complete the scene.

A diplomatic journey after France’s conquest of that country gave Delacroix a rare opportunity to revel in the sights and sounds of this exotic culture, and it shows in many of the paintings and prints on view. “Beauty runs in the streets,” he exclaimed, “Rome is no longer in Rome.” “Women of Algiers” was one of several historical paintings that fascinated Picasso, who produced 15 oils in 1954 inspired by the scene, albeit drastically altered by the later painter’s singular vision. Another jewel not to be overlooked that emerged from Delacroix’s travels is “Street in Meknes.” Exhibited in the Salon of 1834, it simply and lovingly conveys a street scene in Morocco—a formalistic rendering of townspeople, including a beggar half-hidden in the recesses, that draws us into its depths.

Baudelaire, a noted art critic as well as poet and friend of the painter, expressed it this way: “Delacroix was passionately in love with passion but coldly determined to express passion as clearly as possible.”

That discipline encompassed still life with the same vivacity as his heroic figures. “Basket of Flowers” (1848) explodes from the canvas, seemingly giving breath to every color in the natural world and then some. It is easy to see why the Impressionists saw him as the first master of Modernism. In this painting, he wears the accolade shamelessly.

The Met has outdone itself with this paragon of Romanticism and Asher Miller, associate curator of European Art deserves considerable credit. For some it may well be an embarrassment of riches, but what else can you expect from showcasing an out-of-bounds genius artist? Delacroix’s was a greedy appetite that consumed life and all it proffered him. We can be thankful for what he gave us in return.

The exhibition runs through January 6, 2019, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10028. Tel.: 212-535-7710.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief arts critic.

For Highbrow Magazine