Intriguing Exhibit of Self-Portraits Featured at the National Academy Museum

Imagine—a self-portrait show without recognizable faces of the artists. How is that possible? Well, in the mesmerizing new exhibit, \’self\ Portraits of Artists in Their Absence at New York City’s National Academy Museum, it’s not only possible but before your visit is over, you may find your perception of what a self portrait can be turned on its head.

No need to be alarmed. A respectable offering of realistic works show the seriousness of early artists in their depictions of themselves. This curatorial choice is in keeping with a distinguished institution—established in 1825, it boasts over 300 artists and architects on its member roster and over 7,000 works in its permanent collection.

Upon entering, I was struck by Cecilia Beaux’s self-portrait from 1894. She was obviously a beautiful young woman, proud in her pose but every inch a lady. According to Maurizio Pellegrin, Creative Director of the Academy’s school, Beaux is “confident about herself like the Rembrandt painters were. It was a serious period, and you couldn’t’ make jokes.” John Singer Sargent, perhaps the most famous society portrait painter of his time, shows himself in absolute control—exhibiting a manicured beard and cool glance, with chin tilted upwards just enough to give us a perfect expression of haughtiness.

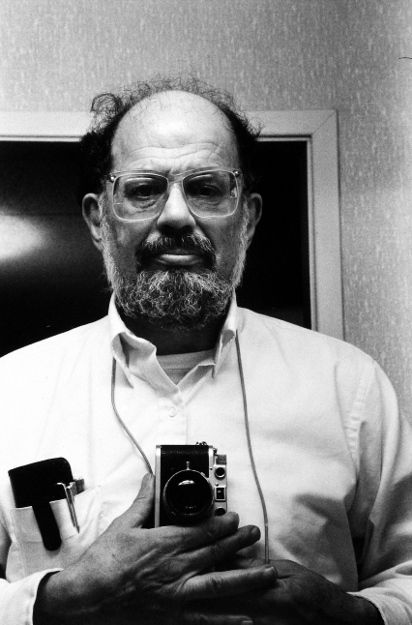

Additional nods are given to the Museum’s founders, like Asher B. Durand and others associated with the Hudson River School, as well as mid-20th century familiars like Andy Warhol and Chuck Close. Wayne Thiebaud provides us with a colorful alter-ego rendition of a tennis player, all but hidden under his vivid blue sunhat—clearly the quintessential California artist. Barkley L. Hendricks, as with many of those represented, chooses photography as an efficient means to convey identity, along with his red sweater. Allen Ginsberg is here as well, camera in hand, capturing a mirror image of himself. Just why he is included among this assembly of career visual artists is unclear.

But the primary focus of the show is a far-reaching exploration of how such personal portraiture has been transformed over the decades. It comprises not only choice works from Academy members, but entries from places as far-flung as Palestine, Lebanon, Iran and China. Perhaps the biggest and most welcome surprise is the extent of entries from women—62 such artists represented from 30 different countries in all. Pelligrin’s response was impassioned and immediate: “It’s not only an act of kindness but a responsibility, a reflection of where the art world is today. There is more experimentation on the part of women in this show than men.”

At no point is the viewer allowed to fall back into his or her predictable place of comfort with respect to the portraiture. One does not stroll through the decades, confronted with a tidy representation of formalistic offerings. Instead, directly opposite the aforementioned fin-de-siecle portrait by Beaux, large C-print photographic portraits by Yemen artist Boushra Almutawakel demand attention. In Mother, Daughter and Doll the trio is posed in a series of panels where their freely open faces gradually disappear before our eyes, until the dark chador covering has all but eclipsed them from view. We can almost feel the “selves” descending into total invisibility--a very powerful and disturbing piece overall. Another C-print nearby utilizing the mother and daughter theme is Catherine Opie’s Self-Portrait Nursing (2004). Fleshy, bold and unpretentious as a Holbein matron, Opie holds nothing back, her tattoos as visible on her naked arms as her nursing breast. Such juxtapositions of works throughout the exhibit do not feel forced but at their best, part of an organic and fluid structure.

The experimentation Pelligrin refers to can also be transformational. Kathleen Gilje paints herself inside the beautifully executed context of Bouguereau’s The Assault; the central figure in a gathering of angelic companions (2012). In I Found Myself Growing Inside an Ancient Olive Tree in Galilee (2015) Palestinian collagist Samia Halaby gives the viewer an intricately gnarled tree. Will we find her inside the foliage or is it in her absence that she becomes more powerful? Rona Pondick gives us herself as a striking ram’s head in yellow and blue stainless steel while Mary Beth McKenzie presents a naturalistic but wary countenance in her oil portrait from 1972, somewhat overshadowed by two floating, amorphous life masks—phantoms from her dream life perhaps? Michele Zalopany’s giclee print (2014) is a ghostly apparition at best, all but disappearing from the viewer’s focus.

The willingness of so many female artists in the exhibit to alter their self-image is bound to raise some interesting questions. Men have obviously been more confident in their public ego throughout history, more determined in how they want to be viewed. Women have had a more difficult time historically as well as culturally in exhibiting a secure identity of their own. Such conditions could lay the groundwork for concealment, but in a free society, a more playful approach to self-identity.

Needless to say, the more contemporary male artists on display manage some hide and seek tricks of their own. Don’t look for Randy Moore as Robin, Batman’s sidekick. The handmade suit on display is empty, all the more provocative as a disappearing act on the part of the artist. Saul Fletcher presents us with a bare upper torso, donning a simple mask as if to say don’t even try to guess who I am. Barry X. Ball shocks with a gorgeously grotesque computer-created likeness projected on a head sculpted in Mexican onyx.

Humor is certainly not absent and a welcome diversion when it appears. Vincenzo Amato’s graphite sketch, The Artist As a Horny Chimp shows a light touch and talent for cartoon caricature while Piero Manzoni’s Merda d’artista (Artist’s Shit, 1961) preserved in a can may not be everyone’s brand of humor. But as Pellegrin admits, it’s part of the attempt “to create a narrative, showing a different way for the public to see the portrait, rather than just a production of one’s own image—you want the deepest thing of an artist, I’ll give it to you,” he says, pointing to the can in question.

A tongue-in-cheek favorite of this reviewer is Annette Lemieux’s pigment print Bad Habits from 2013, which portrays the artist prone in a hospital bed, blowing a circle of cigarette smoke, with a plate of French fries alongside. Lemieux is is obviously not afraid to use herself in art as social commentary—a direction that Cindy Sherman has taken in constantly changing her persona, like her wildly successful Film Still series. Jeff Koons appears in an ad portfolio print, squeezing himself next to a mother pig—a typical nod to his own brand of self-aggrandizement.

The only “selfie” photo in the show is from Beijing, an offering from Ai Weiwei. As the curators would have it, there was a decision to concentrate on portraits before the digital obsession took such a stronghold on the culture at large. However, for those so inclined to capture a self-likeness, a Coney Island style photo booth is set up in a corridor with access to examples of the Academy student work on display.

Other entries which deserve mention are the three self-portraits by the Wyeths—Newell Covers Wyeth (1882-1945) presents himself like a country gentleman, leaning into the foreground like a friendly farmer ready for a neighborly chat; Andrew Newell Wyeth (1917-2009) also places himself in a rural landscape but is posited asymmetrically in the foreground, not confronting the viewer but lost in his own brooding thoughts. Lastly, James (Jamie) Browning Wyeth (b. 1946) is bare-chested, a handsome young man without any observable background to distract. His gaze neither invites nor turns away from our attention. There is something striking and profound about this generational placement and what it says about three masters of the brush through the prism of time.

One of the historic gems of the exhibit is undoubtedly the ink on paper likeness of Umberto Boccioni from 1916. It is the first time this image of the famous Italian Futurist has been exhibited and as it is positioned in its clear plexiglass case, we can see the drawing Boccioni did of his mother in Milan on the backside.

Thanks to the careful planning of Pellegrin, Curator Diana Thompson and Curator at Large Filippo Fossati, the internal structure of the museum’s headquarters with its stunning central staircase, fireplaces and ornate moldings never distract from the exhibit itself. (The Academy’s current home was once the Beaux Arts-style mansion of philanthropist Archer Milton Huntington.) Each piece on display has been carefully, even lovingly, arranged so as not to overwhelm.

One can walk away from this impressive exhibition with the knowledge that self-portraiture is alive and well in the 21st century as it was in the days of our forbearers. It is not so much an absence of the self that prevails but a multitude of selves, an ever changing perspective of what it means to be a creator in the here and now.

The current exhibition at the National Academy Museum & School, 1083 Fifth Avenue (at 89th St.) is on view through May 3, 2015.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.