Inside the World of Animation Artist Chuck Jones

“If I could have been created again, I would want to be a Chuck Jones creation,” reads Whoopi Goldberg’s words on the wall of the latest exhibit at Museum of Moving Image, emphasizing the lasting effect Jones had on the art of animation. The success of the Looney Tunes was in large part Jones’ doing due to his artistic philosophy and caring touch. He famously stated, “All worthwhile endeavors are ninety percent work and ten percent love and only the love should show.” And though most fondly remember the cartoon characters he developed as wild and wacky folks, the exhibit sheds much needed light on the background process and the high level of artistry, both in influence and conception, that allowed Jones to create timeless popular culture icons.

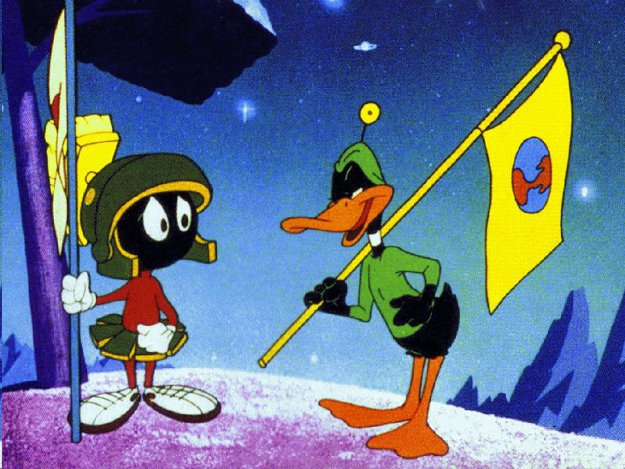

Chuck Jones trained as a fine artist at The California Institute of Arts (then the Chouinard Art Institute). By 1933, just a few short years after his graduation, he was an assistant animator at Warner Brothers. He began perfecting the characters of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Elmer Fudd, Pèpe Le Pew, Road Runner, Wile E. Coyote, Marvin the Martian, and helped bring How the Grinch Stole Christmas to fruition.

These are all characters embedded in American childhood and how we remember them is due to the careful process Jones employed as an animator for WB Inc. He saw his characters as actors themselves, taking anthropomorphism to a new level in the cartoon sphere. The exhibit begins with layout drawings and detailed notes Jones wrote next to the sketchy preliminary drawings of Bugs. Next to the figure he would write how to form the movement: “In a walk: humans, rabbits, or ducks, the shoulders are always an opposite angle to the hips,” and when Bugs is tired “think of a dollar sign” for his shape. It shows his knowledge of traditional contrapposto, but furthermore, viewers can see Jones’ process unfolding before the final cartoon was created. It is indicative of how he was able to imbue his characters with humanness.

Fine art inspiration takes other forms in his animation, such as his application of Edgar Degas’ techniques for constructing ballerinas. He was drawn to the angular symmetry yet free flowing and expressive lines of Degas’ ballerinas and the same approach is seen in Bugs’ spindly, wavering legs. He also remade Van Gogh’s painting of his bedroom at Arles in a cartoon of J. Michigan Frog. He clearly enjoyed impressionistic artists for their expressive application of paint and looked to (and did) achieve the same kinds of emotive reactions on the part of his viewers.

It was how Bugs Bunny was able to move from being a lovable cartoon to an image of strength and hope during WWII by being “cool under fire” in the cartoons. Viewers saw aspects of humanity that they recognized within themselves and others through Jones’ lifelike characters. In his own words, “Just as the actor demonstrates a part not by what he looks like, but by how he moves, so the animator takes simple graphics and brings them to life.”

On display is Jones’ famous directorial work “What’s Opera Doc?” which reintroduced classical Wagnerian music into the mainstream all while being a parody of the opera genre. Alongside the screening of the short film are color guides, sketches, and notes allowing viewers to compare and see preparations from the finished product: it is clear how direct Jones’ vision was and how meticulously he planned its execution. It’s nostalgic while enlightening, providing a reminder of childhood while showing how cultural absorption can happen at any age.

Other short films on view are Duck Amuck, poking fun at the animation process itself, and Jones’ abstract cartoon Dot and Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics, a real achievement in terms of personification and graphic design. Using minimalism, which was sweeping through the arts world in the 1950’s and 60’s, Jones’ conceived a tale of unrequited love between a line and a dot. Dot is in love with curls instead of straight-edged and “boring” line. The implications are both humorous and innocently touching. It takes rare talent to bring humanness to the most basic graphic forms but Jones does it well.

Therein lies the legacy of Jones’ animating brilliance: telling stories that make viewers laugh through the expressively human qualities found in the unlikeliest of subjects. His reach has gone all the way to influence the Pixar creative team. John Lasseter, Chief Creative Officer at Pixar and director of Toy Story and Toy Story 2 provides commentary before each of Jones’ short films and voices his admiration for the inspirational qualities of Jones’ approach to animation. It’s no surprise that the Pixar movie audiences flock to the theaters to see films that are conceptually tied to the warmth, weirdness, and humanity of Jones’ characters that sometimes fluctuate between protagonist and antagonist but always create a lasting impression in the minds of viewers.

Lasseter even says, “At Pixar, we love Chuck Jones and his spirit, and it’s in every single film that we do.” Aside from the playthings in the Toy Story trilogy, there are the lovable monsters in Monsters Inc., the gruff and senile Carl in Up, the foodie Remy in Ratatouille, and the heart-warming romantic robot in Wall-E: Chuck Jones’ influence is undeniable in the digital characters seen today.

The exhibit’s retrospective reminds viewers of the profound scope of Jones’ talent in making animation a higher art form in its creative outreach and inspiration, while still maintaining its accessibility through his ceaseless focus on the lightheartedness and sympathetic aspects of the human condition.

Author Bio:

Sabeena Khosla is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.