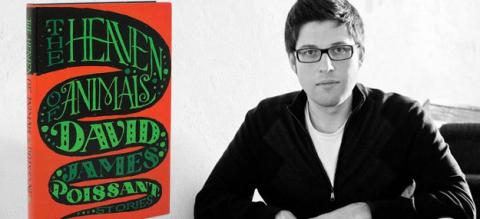

Love, Loneliness Are Focus of David James Poissant’s' The Heaven of Animals'

If a purpose of literature is to expose universal truths about life and human nature, then David James Poissant’s The Heaven of Animals has done its job. Poissant, a celebrated young writer whose stories have appeared in such publications as The Atlantic Monthly, The Chicago Tribune, and The New York Times, and whose work has already garnered impressive literary awards and critical praise, presents layered storylines and realistically flawed characters in his first collection of short stories.

Set largely in small towns of the American South and Southwest, especially in Florida, Georgia, Arizona, and California, the 16 stories in The Heaven of Animals feature characters who grapple with all the familiar philosophical uncertainties – love, sex, religion, death, and the inevitable passage of time. Their problems fill the spectrum of human experience, from the death of family members to divorce, mental illness, marital tensions, infidelity, and growing up, all written with a naked honesty that reveals the universal human condition.

Although each story in this collection stands on its own, Poissant creates a literary world that holds the separate narratives together through overlapping characters and settings. In his opening story, Lizard Man, a hardened, working-class father in south Florida wrestles with the memory of finding his teenage son kissing another boy, the shock of which led to a violent confrontation that destroyed his relationships with both his son and his wife; in his final story, The Heaven of Animals, Poissant returns to this same character as the man tries desperately, decades later, to understand his son and to salvage their relationship before he dies of AIDs. Similarly, in the first part of The Geometry of Despair, a young couple mourns the death of their infant daughter and attempts to revive their disintegrating marriage, while, in the second installation of the same story, the memory of this past trauma affects the way they parent their second child and relate to one another.

However, many of Poisssant’s narrative connections, while equally effective in unifying his collection, work more subtly. Refund and The Disappearing Boy, for instance, feature unrelated plotlines and characters, but both take place in River Run Heights, a fictitious housing development in Georgia. Understated connections like these establish a small universe for Poissant’s stories, allowing the reader to disappear into middle-class southern America, where imperfect characters struggle to understand existence and try feebly to fix their mundane, dysfunctional lives.

Although The Heaven of Animals does incorporate the occasional hackneyed literary theme, the overarching subject of these stories, the question Poissant’s characters return to over and over again (and the question that sets Poissant’s work apart), is the broken way humankind relates to one another. Above all, these stories are about relationships. Husbands and wives, fathers and sons, brothers, cousins, friends, and lovers, the characters in The Heaven of Animals fight ineptly to be heard, to be understood, to be loved by the people in their lives, and to love them back in their clumsy ways. Poissant probes our aching desire to be close to others, exposing all the things that divide us: the uncommunicated desires, the ugly truths hiding just below the surface, the open wounds that won’t heal.

True to its title, most of the stories in The Heaven of Animals include references to wildlife, which often represent the emotional condition of a character or the state of a relationship. Sometimes, an animal is a prominent part of a story’s plot, or acts as a character, such as the giant alligator set free in Lizard Man, the bison that kills a desperate mistress in Land of the Great Land Mammals, the wolf that talks to the narrator in the dreamlike What the Wolf Wants, or the wife’s beloved beagle in Me and James Dean. In other stories, Poissant makes only a passing reference to animals, as when he refers to a mentally-ill character as “a wounded bird” in The End of Aaron or when the main character of The Heaven of Animals reflects on his son’s lifelong passion for sea creatures. Although recurring and highly symbolic, Poissant’s use of animals as a literary device never feels forced or obvious, but rather charges his writing with meaning and unites his narratives under a common motif.

The true power of Poissant’s storytelling, however, arises from the complexity of his plots and the forceful simplicity of his writing. Almost every story in this collection appears straightforward on the surface, only for a subplot (or several subplots) to emerge down the line. Amputee seems to be about a man attracted to a teenage girl but is actually about the narrator’s divorce from his wife and about the girl’s attempts to come to terms with the bone cancer that will eventually kill her. Nudists seems to tell the story of two brothers reuniting after many years, but the deeper subplot of the narrative involves the death of the main character’s wife and his inability to forgive himself or his brother for the past. Lizard Man is about a man accompanying his friend to say goodbye to his deceased father’s house, but it is also about his own issues with his gay son. Poissant artfully incorporates flashbacks and memories in his writing, weaving parallel plotlines to create deep stories, rich in meaning and feeling.

His writing style, at turns conversational, narrative, and poetic, depending on the tone of the story, carries the strength of simplicity, its straightforward sentences unburdened by complex structures or flowery modifiers. While he touches on the most serious of subjects, he never takes himself too seriously, tempering life’s dramas with lighthearted humor. Most significantly, though, he sculpts layered, realistic characters through believable dialogue and through all the things he doesn’t say, allowing the reader to interpret the characters’ words and actions rather than explaining their motives outright.

It is easier for us to understand a thing when it is removed from our personal experience. In The Heaven of Animals, Poissant presents the state of human relationships to us in the form of animals. Through his artful storytelling, he gives us a glimpse into the loneliness, the brokenness, and ultimately, the importance, of our emotional connections with others.

Author Bio:

Melinda Parks is the pen name of a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine