Why Ralph Ellison Still Matters

From The Root:

“... Literature is an affirmative act, but, being specifically concerned with moral values and reality, it has to deal with the possibility of defeat. Underlying it most profoundly is the sense that man dies but his values continue. The mediating role of literature is to leave the successors with the sense of what is dangerous in the human predicament and what is glorious.” —Ralph Ellison, 1972

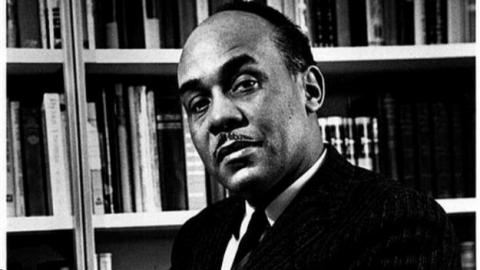

On March 1, 2014, Ralph Ellison would have turned 100. On that day, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem devoted a day to readings from Ellison’s classic novel, Invisible Man. In February the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in his honor. Earlier this month, in Ellison’s birthplace of Oklahoma City, an academic conference celebrating his centennial was held featuring The Root’s own editor-in-chief, Henry Louis Gates Jr., as keynote speaker. Also this month, the National Jazz Museum in Harlem launched an exhibit centering on Ellison’s record collection.

Yet considering Ellison’s central place in 20th-century American literature and his sterling achievement as a black American thinker, more attention should be given far and wide. To address this lack of due attention, here are three reasons that Ralph Ellison still matters.

1. The Achievement of Invisible Man

Never out of print since it became a best-seller in 1952, and winner of the National Book Award in 1953, Ellison’s fictional masterpiece is generally recognized as one of the most influential novels of the 20th century. This is the tale of the often slapstick (mis)adventures of a nameless Negro American protagonist whose blues-drenched, pinball-like journey from the South to the North and from rural to city not only mirrored the historical trajectory of black folk, but whose search for identity resonates, even today, with all.

The historical and psychological depth, the capturing of the range of polyglot American speech patterns, the intersection of individual desire for leadership and the ideological and political realities of the time, and the range of literary allusions—from Negro folktales and fictional predecessors ranging from Melville, Dostoevsky, Twain, Hemingway and Faulkner to James Weldon Johnson and Richard Wright—all combined in Ellison’s imagination and were conveyed in eloquent prose. The power of Invisible Man to still reach readers in their guts, hearts and minds—to relate to their sense of life, whether male or female, or from whatever ethnic or cultural background or nationality—is well-stated in the novel’s closing line: “Who knows but that, on the lower frequencies, I speak for you?”

2. Ellison’s Definition and Defense of Black American Culture Over Race

Ellison once wrote that the American “writer has a triple responsibility: to himself, to his immediate group, and to his region.” African Americans (whom Ellison’s generation called Negro Americans) were his immediate group, and following predecessors such as Langston Hughes and Alain Locke, Ellison embraced affirming what he called the “Negro idiom,” an attitude and way of life that manifests the way we move, make music and dance, play in speech and sport, style in cuisine and fashion.

Ellison knew that race was built on surface perceptions that hid deeper human meaning and identities derived from culture. In fact, the Negro idiom, as he defined it, is integral to American culture overall. Comprehending culture and not confusing it with race was a key to his artistic liberation and is still instructive for us now.

In an essay defending black youth, titled “What These Children Are Like,” Ellison defined culture as “how people deal with their environment, about what they make of what is abiding in it, about what helps them find their way, and about that which helps them be at home in the world.”

Culture is also a storehouse of values. In 1963, in an essay titled “The World and the Jug,” Ellison famously took white liberal literary critic Irving Howe to task for elevating Wright’s anger in Native Son over his more “modulated” approach in Invisible Man. Ellison, in one of the best literary beat-downs of the 20th century, informed Howe that Negro life isn’t only a burden “but also a discipline—just as any human life which has endured so long is a discipline teaching its own insights into the human condition, its own strategies of survival ... Crucial to this view is the belief that their resistance to provocation, their coolness under pressure, their sense of timing and their tenacious hold on the ideal of their ultimate freedom are indispensable values in the struggle, and are at least as characteristic of American Negroes as the hatred, fear and vindictiveness which Wright chose to emphasize.”

3. The Fulfillment of His Civic Duty as an American Writer and Citizen

Ellison played a central role in the development of what became PBS, the Public Broadcasting System. This was one example of his civic engagement with the nation. But his main means of engagement was with his pen and typewriter. In the cauldron of the 1960s and the black power and Black Arts movements, the political fervor of the times led some to mischaracterize Ellison as standing aside from the movement.

Yet Invisible Man itself not only reflected the history of black Americans from the mid-19th century through the mid-20th century. It was also a portent of the civil rights movement. As the epigraph at the beginning of this essay confirms, the creation of literature was not, to Ellison, a frivolous departure from structural or social realities. Writers, he often said, create or reveal hidden realities by asserting their existence. Ellison believed that one of his tasks was to explore America and to describe it in order for the promise of the nation to become a reality. To Ellison, this responsibility was almost sacred.

In 1967 Ellison was interviewed by three young black writers. They asked: “What do you consider the Negro writer’s responsibility to American literature as a whole?”

Ellison responded: “The writer, any American writer, becomes responsible for the health of American literature the moment he starts writing seriously ... regardless of his race or religious background. This is no arbitrary matter. Just as there is implicit in the act of voting the responsibility of helping to govern, there is implicit in the act of writing a responsibility for the quality of the American language ... ”

In a consideration of Ellison’s contemporary significance, his interviews, essays and letters should also be factored in, as well as his uncompleted second novel, Three Days Before the Shooting. Ellison entire body of work remains relevant because it reverberates with a vision of American possibility as magnificent as that of any other writer of the 20th century.

Author Bio:

Greg Thomas, after a two-year stint as jazz columnist for New York’s Daily News, has gladly come back home to The Root.

This article was originally published in The Root.