‘The Maltese Falcon’: Fact or Fiction?

It’s no surprise that some writers walk a thin line between the world of fiction and the world of fact. As Dashiell Hammett, that master of the hard-boiled detective story told the New York Evening Journal in 1934, “All of my characters are real. They are based directly on people I knew or came across.” In Owen Fitzstephen’s Hammett Unwritten from Seventh Street Books, Hammett is revisited by the cast of unforgettable characters he presented us in his legendary The Maltese Falcon, and we discover just how thin the line between reality and imagination really is.

It’s quite a journey that Fitzstephen (the pseudonym for author Gordon McAlpine, but more about that later) takes us on with Hammett. But first, he gives us the actual 1922 newspaper clipping from the San Francisco Examiner describing the murder of one Louis Doyle, the sea captain who had transported the black falcon statuette from Hong King. Before expiring, Doyle manages to place the falcon in the hands of none other than Samuel Dashiell Hammett, a twenty-six-year-old Pinkerton detective. Not a bad beginning for a would-be writer.

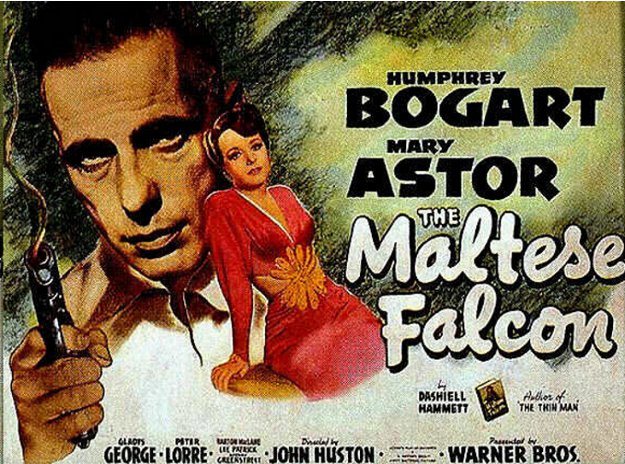

We jump ahead to Hammett’s hard-drinking, glamour-splashed days in Manhattan in the early ‘30s, his head awash with the publication of The Thin Man. Enter Moira O’Shea fresh from a hospital for the criminally insane and a co-conspirator in the falcon case murder (filmgoers will remember her as Mary Astor, the conniving co-conspirator in John Huston’s film of the famed falcon). He gives her the statuette, maybe to convince himself that he doesn’t buy the mumbo-jumbo about its mystical powers.

Not surprisingly, things spiral quickly downward for our hero—a tryst with his former Pinkerton secretary that goes sour; a spooky encounter with Gaspereaux, the devious Big Man who has dedicated his life to possessing the real falcon (Sydney Greenstreet from the film); and a 1951 stint in the Federal Penitentiary in Ashland in Kentucky for refusing to testify against Communist cohorts. While there, he encounters Emil Madrid, another conspirator and a dead ringer for the Peter Lorre character in the film. Madrid reminds him writers are essentially criminal too. “They steal people’s lives, is that not so?”

If this cast is not colorful enough, John Huston as an ambitious upstart Hollywood director and Lillian Hellman, the successful playwright who co-habited with Hammett (no easy task) add spice to the proceedings. It is Hellman who sticks by her beloved “Dash” through what could be the longest writer’s block on record, fearing for his growing obsession with the falcon. Given Hammett’s death in 1961 from lung cancer it seems unlikely that his eventual recovery of the bird made much of a difference.

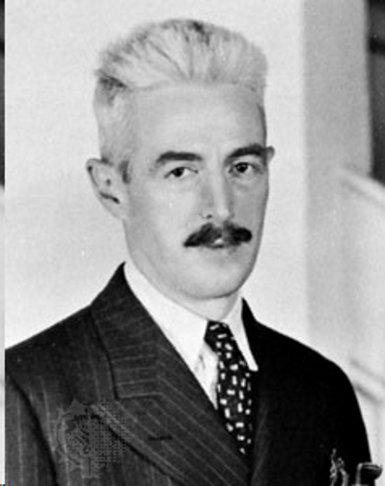

The biggest mystery of all, however, concerns Hammett Unwritten itself. In Gordon McAlpine’s afterword, he admits to the 2012 discovery of the manuscript and the falcon in the Lillian Hellman collection at the University of Texas, Austin. Subsequently, he recognizes the author’s name, Owen Fitzstephan, as a character in Hammett’s novel, The Dain Curse. Fitzstephan not only resembles Hammett physically but is that novel’s own evil mastermind. McAlpine concludes that Hammett himself wrote the book as a tightly-focused memoir during the last year of his life.

Certainly the dialogue and setups are as quick and sharp as Hammett’s (or Hellman’s for that matter). So what is the explanation for Hellman’s silence? McAlpine believes it lies in her introduction to a posthumous collection of his works. She says he kept his work “in angry privacy” and that the fact she was with him up to his last day may be due to the fact that she never asked.

We may never know the answer, but maybe this new manuscript is more than enough if it brings new readers to this elusive writer.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.