Philip Schultz and the Perceived Conundrum of the Dyslexic Writer

When we think of failure, our thoughts do not first adhere to beauty, emotional truth, and the deep resonance that introspection allows; the timbre of an experience that can call to us in life’s darkest hours be they night or despair. But this is precisely what poet Philip Schultz’s work pulls forth, whether poems such as those in his collection Failure, winner of the 2008 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry, or Schultz’s beautifully told account of his childhood in the “dummy class” and life as an adult with a learning disability in My Dyslexia.

The American mythos centers upon aspiration, mobility, and success, but flips and flops between two sides of the coin, our currency. On one side, we have the melting pot—make us all one big mish-mosh of sameness; blended. On the other, we find an embrace of difference—diversity. And yet difference continues to challenge us; and we rely heavily on our conceptions of normal. The norm. The ideal. The comfortable middle. When difference is boxed into disability, we still revert to alienation, false conceptions, and, too often, judgment and low expectations.

The title of Schultz’s sixth book, Failure, published in 2007, evokes an intimacy appropriate to the range of inviting work encapsulated in the collection. Some poems are deeply personal, such as the eponymously titled “Failure,” with its breadth of emotion and memory following the death of Schultz’s father, a “comical” man, a “failure,” a man whose “weariness overcame him/finally” and a son “who left town/but failed to get away.” Other poems, on the surface of things, tell someone else’s story, seemingly less personal and yet cutting deep. Take a poem like “Exquisite with Agony,” in which we begin with a generality that pushes forth immediate and specific:

Only the guilty ask why

they deserved such punishment,

only the stupid expect kindness.

We reside with the poet; we reside with ourselves, those dark and private moments, until, then: “Yesterday, in our town, /a two-year-old girl drowned/in her grandmother’s pool.” And, she, the grandmother—and, we, the reader—“find everything once luminous/and unyielding smashed.”

The second half of the slender volume is taken up with 50-plus pages of “The Wandering Wingless,” an undulating compendium of multi-voiced characters, deeply moving, sometimes brief, but building in merging lines to express intertwined lives and parallel lives. The poem, told in short segments, takes on up close subjects as seemingly diverse as racial inequities; mental illness; dogs as companions, as income source, as readers of people; revolution; ECT; poverty; grief; 9/11; and the struggle to make a path in the world. Schultz explains in a 2011 Norton interview, how he had to “balance and juggle a variety of narratives simultaneously” - a talent associated with the finest and most complex writing, and a strength of dyslexics.

When Failure won the 2008 Pulitzer, Schultz was a writer who had attained modest recognition, making his livelihood from The Writers Studio, a writing school he had founded in New York City some 20 years earlier. In an ensuing write-up in The New York Times, a notably cheerful piece by Robin Finn, Schultz remarks, “Fitzgerald said there are no second acts in American literature…. I think I’ve disproved that.” F. Scott Fitzgerald, another intimate of failure, and success, likely recognized the same fallacy, as Kirk Curnutt, vice president of the F. Scott Fitzgerald Society proposed earlier this year with NPR’s Audie Cornish. The “second act” line arises from a Fitzgerald essay “The Lost City,” in which Fitzgerald writes about how, as Curnutt presents it, “we are always caught between the past and the present, and we carry the burdens of both.”

Fitzgerald, one of the most lauded men of American letters—with merit, The Great Gatsby is often upheld as an emblematic Great American Novel, its themes pronouncing American excess and success—was, like Schultz, dyslexic. When Schultz won the Pulitzer in poetry, at age 63, he had not yet spoken publicly of his learning disability. The diagnosis—the word—assigned meaning and structure to a collection of traits and difficulties, a collection of perceived failures, though the poetry collection of the same name referred more directly to Schultz’s father, not to Schultz’s life-long relationship with language and its tangles. The diagnosis had arrived for Schultz’s son only a few years earlier, opening up a corridor of mirrors. Recognition.

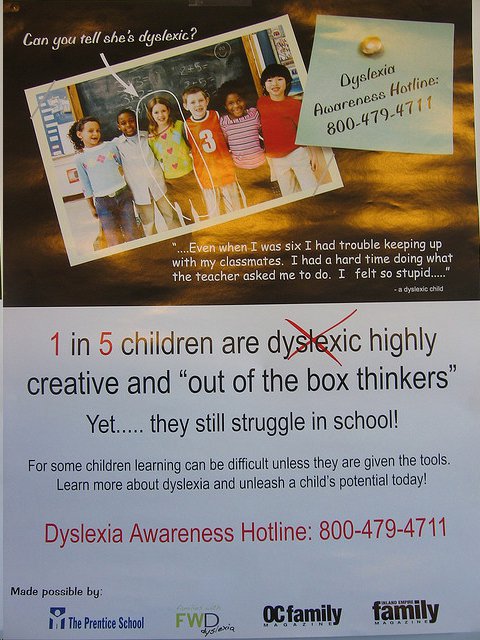

Dyslexia is a learning disability—a neurological pattern affecting five to 10 percent (a conservative number) of the population, according to neurologist, and writer, Oliver Sacks, who himself has face-blindness, “severe congenital prosopagnosia,” a difficulty or inability in recognizing not only acquaintances, but close family and friends. Prosopagnosia is “estimated to affect at least two percent of the population—six million people in the United States alone,” as Sacks writes in his book The Mind’s Eye. Remember The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat? When Sacks wrote this earlier book, which came out in 1985 taking up related subjects, he had not yet diagnostically recognized his own life-long relationship with prosopagnosia, having come up with compensatory strategies for the disability: focusing on identifying features, such as a person’s gait, hair color and other individual details. Whereas more typically we take in a person as a whole, not through their separate parts.

The word disability, like the word failure, is telling. We often shape difference—including dyslexia, a neurological and cognitive processing difference—in terms of the negative, particularly when it comes to knowledge acquisition and social skills.

Schultz’s success, in the aftermath of the Pulitzer, brought him face-to-face with this contradiction: failure. Failure had brought him a new, heightened level of recognition. His Failure had brought him success, and it is as though some inner truth revolted, seeking the relationship between past and present, as he had done in different form in his poems, encapsulated in work like Living in the Past, which is curiously described by Publishers Weekly (four years before Schultz’s Pulitzer) as not formally or thematically new in its focus “on American Jews' postwar inheritance.” As though Robert Pinsky and Adrienne Rich, the poets referenced, having already spoken on American postwar Jewry, had wrapped it up. On the contrary, Schultz has much to say, and much to add to the discussion, of themes of loss, and accompanying guilt and “failure,” whether postwar driven, or not.

How much more resonant and meaningful failure is, than the approbation and approval of success. Yet, how important approbation—for it marks something akin to understanding. Within failure, we find ourselves outside; we feel too often alone. But kindred relationships and a shared language lie therein.

In the often hidden world of neurological diversity (a variety which is necessary and advantageous, Thomas Armstrong, PhD, argues in his book The Power of Neurodiversity), LD—Learning Disability—signifies the challenges. Being different often entails being “the Other.” In an American world, where the primary currency is often sameness, difference can only be traded up when it elides into a level of eccentricity and uniqueness that suddenly translates into success. Think Einstein, our sine qua non of genius, who, like Schultz is believed to have had dyslexia. Like many other children with dyslexia who do not receive the support available with diagnosis and re-tooled techniques, Einstein did terribly in school. Learning disabilities, for many, still carry stigma and preconceptions, accompanied by memories for middling to older generations of what was once termed the Resource Room—where we find the stupefied silence of a child who cannot pass words from paper into the world, who cannot read aloud, (many) who cannot read. Numerous children have slid into adulthood dogged by this disability formulated as failure.

We expect reading to pass from instructor to student in a standard progression -- and mostly it does. There might be a few deviations and a little extra effort required, confirming, each time, our belief in a common standard. Defining, by levels of reading agility and speed, our conceptions of intelligence, even brilliance, accompanied by the understanding that intelligence correlates with good behavior; and thus its inverse: bad behavior verifies a failure of intelligence.

Failure is un-American, the dark underbelly of the dream, the space under the boot instead of the upward glance of the boot straps from which we instruct each other to pull ourselves up. We—this general we of American readers—have paid more heed to Schultz, his Failure and his “failure,” because of the accolades of success. (Writer Meg Wolitzer touches on the corollary sketchy relationship between talent and success in a recent Financial Times article, “In Search of the Real Thing.”)

Isn’t failure more interesting when it is part of a success story? When we think of difference, we think of ways to instruct upon finding sameness. When we think of adversity, we wish it away. And yet—

In 2011, Schultz sat down on stage with dyslexia expert Sally Shaywitz, M.D., neuroscientist, professor, and co-director of the Yale Center for the Study of Learning and Attention, for a discussion at the Churchill School in New York City, a school serving K-12 children with learning disabilities, with a particular emphasis on dyslexia. Schultz had sent Shaywitz a copy of My Dyslexia. Shaywitz, with decades of experience in the field, says, “I was so moved by it, I looked up his phone number and called him that night,” affirming that even with many books already in the field, this one tells “the heart of dyslexia.”

The memoir presents potent testimony of a child’s experience being the “dummy” and the adult Schultz’s recurring need for rapprochement between the self who struggles to read and the self who lives and yearns for the power of language, poems, and stories. Even now, “As I read, a kind of subtle bartering between uncertainty and hunger for knowledge goes on in my mind, in which I must conquer a feeling of hopelessness and anxiety.”

But “[t]he fact that I couldn’t read,” Schultz writes of his eleven-year-old self, “didn’t mean that I never would, I thought. I always assumed I would one day, and what difference would it then make?”

When Schultz’s reading tutor, a retired grade school principal brought on in his fifth grade year to hold off another expulsion earned through bad behavior and what was considered stupidity, asked what Schultz would like to be when he grew up, “Without a moment’s hesitation, I answered that I wanted to be a writer,” Schultz writes, causing his tutor, “a good-natured, slightly stern man” with a belly that moved in “gelatinous waves,” to erupt in unceasing laughter.

When schoolboys called Schultz a “dummy”—“I did what I saw my father and my uncle [and]…all the tough guys in all the movies and on TV did when insulted—I hit kids, with all my strength, to make them stop laughing at me.”

Schultz, with intense intervention, enduring faith and repetition from his mother, did learn to read, though it would be decades until the label dyslexia was understood to apply to his predicament. A label that can, now, open doors and throw the intense light of understanding across a dark room of confusion and hopeless repetition of techniques that work for so many but remain close to useless, and therefore even harmful, for the select—estimated at upwards of 10%—who, diagnosed or not, have dyslexia. While having a learning disability can bring great discomfort, sometimes shame and confusion, bullying, anxiety, fear; knowing and naming it can offer not only reprieve but techniques, understanding—and comrades in the particulars that feel so unique.

After the Pulitzer, Schultz began, almost compulsively, to bring up dyslexia and his childhood struggles with reading, going on to write the beautifully candid My Dyslexia, published in 2011. Its release was preceded by a stirring New York Times piece, “How Words First Failed and then Saved Me”:

I didn’t know then that I was beginning a lifelong love affair with the first-person voice and that I would spend most of my life inventing characters to say all the things I wanted to say. I didn’t know that I was to become a poet, that in many ways the very thing that caused me so much confusion and frustration, my belabored relationship with words, had created in me a deep appreciation of language and its music….

Shaywitz’s book Overcoming Dyslexia lays out neurologically typical reading processes and methods, and is immensely useful in understanding indicators and techniques for troubled readers and signs of dyslexia, in children and adults. The book catalogs dyslexia’s frequently accompanying strengths—assets—in higher-level thinking processes, including strong capacity for specialization, excellence in content in writing (not spelling), “a talent for high-level conceptualization and the ability to come up with original insights,” big-picture thinking and an “inclination to think out of the box.” Famous dyslexics, exhibiting traits such as these, include Virgin Airlines founder Richard Branson; Tom Cruise; esteemed scientists and surgeons; Pulitzer-Prize-winning playwright Wendy Wasserstein; and writers such as W.B. Yeats, Agatha Christie, John Cheever, John Grisham, Richard Ford, Stephen Canell, and John Irving.

John Irving, like Schultz, learned more about himself and his dyslexia through having a child diagnosed.

His teachers said that Brendan comprehended everything he read but that he didn’t comprehend a text as quickly as his peers; they said that he could express himself as well as, or actually better than, his peers but that it took him longer to organize his thoughts on paper. This sounded familiar to me.

Irving describes, for Shaywitz, being told he was stupid, and lazy. But he can now perceive his dyslexia as an advantage:

To do anything really well, you have to overextend yourself. …I came to appreciate that in doing something over and over again, something that was never natural becomes almost second nature. [And]…in writing a novel, it doesn’t hurt to have to go slowly. It doesn’t hurt anyone as a writer to have to go over something again and again.

Stephen Canell, writer of classic television hits such as The Rockford Files and The A-Team articulates, “Dyslexia may be very difficult for a child in school, but it may also be a great gift. [T]his world needs abstract thought and creativity desperately… [and] it is the rare person who comes up with a new question or a new insight.”

Shaywitz reminds us of occasions where a person can excel overall within a profession, despite failures or deficits in areas considered important, which may in the end be insignificant and surmountable. “Slow reading lawyers, poor-spelling writers, and surgeons who failed anatomy in medical school—they all flout conventional wisdom.” For Schultz, one of the most significant benefits of the Pulitzer—of “success”—is what he describes as ways in which it has helped him lessen self-recriminations. “I’ve gotten off my case,” he told Shaywitz, no longer feeling as embarrassed or humiliated by situations like messing up an introduction. “I see the advantages of this [dyslexia] and I don’t know that I would easily give them up—to be ‘normal,’” Schultz says.

In My Dyslexia, Schultz writes of “a kind of subtle bartering between uncertainty and hunger for knowledge.” He has described how the methods he employs in his writing school, The Writers Studio, applauded for its intimacy, emerged from his experience with dyslexia, though unlabeled at the time. Schultz imagined himself into being other people, inhabiting other stories—“persona writing”—and he imagined himself as a boy who could read, though not until age eleven. In this way, and through repetition and material that mattered to him, he became a boy who could read. As the method pertains to his students, Schultz describes how, “If they could invent a character who didn’t have their own misgivings, who could perhaps tell their story from an angle, or a point of view that would add something to that story, it would free them.” A sort of empathy; a stepping out of one’s own life and limitations, in order to more fully render a related but distinct world, and how it would be to exist in it. Making it real on the page.

Norman Doidge, M.D., in his book The Brain that Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science, relates ways in which science (through MRI’s) registers similar neurological changes, both in the brain and through patterns of behavior and ability. This nexus of science, action, imagination, and creativity remains incompletely explored; and presents fascinating relationships and arguments for reconceptions of "failure” and “success.” Human imagination (also a form of imaging) can play an immensely powerful role in rendering alternate lives, a pleasure every writer knows. These studies explore—as indeed, Schultz’s own method does—the complex relationship within the mind between reality, creativity, and thought.

Schultz refers to his being a writer as “to a degree, wonderfully preposterous,” recognizing the incongruity between severe reading problems and fluent, more than fluent, writing. Writing, as a craft and a calling, quite naturally holds these contradictions. Expertise, in writing, does not remove even skilled veterans from intermittent feelings of inadequacy and incompetency, in the face of the enormity of a writing task.

Charles Baxter writes in the essay “Full of It,” included in the anthology Letters to a Fiction Writer, edited by Frederick Busch, “The trouble is that the first stage—of pretending to be a writer—never quite disappears.” An element of faking it persists even after accolades; and if we are faking it—even after years of practice and experience—well then, how close is failure, continuously, for a writer? At any moment, it is as if the whole ruse could fall apart. We wait, ready to be exposed, for that moment when we may be called upon to speak for the words, required to bring sense to marks on the page, or the marks of experience—our own, others—embedded within.

And of course writing, as a professional endeavor, is marked by frequent rejection, a continuous and ongoing sort of failure. Baxter describes a version of this, “I…felt that I had become an expert on failure and the day-to-day management of despair. Much of the time my mouth was full of ashes.” Then, finally, for Baxter, came a glimmer of approbation from an editor at the Michigan Quarterly Review—for a story about failure. “For the next five years I wrote about failure. It had become my subject, my koan, my home base, my infinitely renewable resource. The abyss turned into a mineshaft.”

Frederick Busch, in his wonderful collection A Dangerous Profession, traverses extensive writing terrain. In the essay, “The Children in the Woods,” Busch concludes, “Fiction that matters, of course, cannot be about living happily ever after. …It is about living with a truth you’ve discerned but don’t want to know. It is about hunger, how hunger comes first.” Here, hunger holds a menacing double edge—the redeemable, if perhaps sometimes perilously insatiable hunger of the writer for words (and understanding) and their pursuit, alongside hunger as subject, hunger within the human condition, sometimes as menace. This second “hunger” pertains to the triumph of self-serving ill will as represented by the stepmother in “Hansel and Gretel,” willing, even eager, to forsake the children in order to conserve limited resources for herself; and, from the same story, the witch with the gaping mouth of the oven—in the classic fairy tale, but no less within the horrors of the Nazi death camps, as Busch adroitly connects them. Ovens stand in for menacing and incomprehensible chasms of human behavior.

Writing compels us to look into the abyss—not to fall; to stare, to reach; not to jump, and not to be consumed by horrors. Writing demands risks—offers, in return, the hazardous pleasures of solitude transformed into shared experience. My Dyslexia has done just that. The exploration reads with a straightforward honesty that is rare enough to attract attention. The experience of spending time with and in the book makes one want to hold it aloft, share, and hand out copies.

How glad we should be, Philip Schultz believed, with that purity of understanding and certainty that can accompany fleeting moments of childhood, and come from rare inexplicables within, that he could become a writer. He already had within him the capacity and talents matching the endeavor that seemed most remote, to an undiscerning and unknowing eye: to write.

Despite the evidence of science and literature, some continue not to comprehend the complexities and realities of dyslexia. At the September 2011 Churchill School event, Shaywitz remarked to Schultz, “To this day there are people who claim dyslexia is not real.” Schultz returned a look of incredulity, and Shaywitz asked, “What would you say to these people?”

“In mixed company?” Schultz replied. “That kind of ignorance is just so dazzling, so befuddling,” and Schultz spoke again of his son.

Even if it can remain difficult to make sense of the underlying systems in a reading disability, witnessing a physically visible aversion to reading makes clear that the expected relationship between symbols and meaning has broken down.

When the sun shines at full strength, we turn our heads from its brightness; we know not to look directly. Even more, we cannot. And so picture a child, words chopped into dancing letters, the shapes wriggling and reversing, printed, but not indelibly, on the page before him. He turns his head away, and it is as though he is shielding his eyes, as though he is allergic to those letters—those dear intimate friends we know as words. The child loves stories, will listen to them for hours, but to look at those words, simple ones even, let alone to imbibe them—decode them—is near impossible. For indeed, they are presented in code, mysterious and unintelligible. With no key. Try, without the key, and persistently he will fail. A failure that can seem incomprehensible to those for whom the key works, at first with some twisting and chiding, with practice, with use, and then effortlessly. Do we think, each time we unlock the door to our home, about the action of inserting the key, how it must align, the particular twist, its direction, the degree of the turn? Like so many of our actions, it becomes second nature, obvious and absurdly simple—as long as the lock is not jammed, and we have the key.

In watching a child with a learning disability, particularly with the tight regard of a parent or intimate, we see the glare of difference; we see the taken-for-granted nature of what we perceive as normal; we see the ways, each day, we push ourselves more fully into particular habits of conformity, a striving that has likely been tended since childhood, then continued, with greater or lesser degrees of effort, into adulthood; and we see the ways in which we, even so, persist in abnormality or eccentricity. We see the differences by which we still feel marked, even if they register invisibly. And if these differences are merely a matter of perception, how closely do we perceive—does this draw us apart, or draw us closer to the mass of humanity? We cherish sameness, reliability. We cherish that which registers as unique—a startling and interesting jewel.

Joyce Carol Oates writes,

If it’s your ambiguous destiny to be a writer, you already know that no one can tell you what to do, how to behave; still less how to think, and how to feel about yourself. …To be a writer…is to plunge into the unknown that lies within. The exterior or social self is a shell that can protect or stifle you depending on the accident of circumstance.

Living with neurodiversity, something we can all learn from, entails straddling comfort and discomfort, entails accepting contradictions—deficits or difficulties nestled up close with exceptional strengths and talents; failure and success chasing each other. Just as inadequacy in the face of words, and pleasure in the power of words, both exist within dyslexia, they co-exist within writers. The construction of worlds on paper, whether a reconstruction or imagination, is magical; and yet too often we fault ourselves for falling short. Within this tension lies the drive, the need for repetition of this hopeful, despairing act: rendering and accepting what it means to be alone, while reaching for the community that can be found in words, in books, in writing and reading.

Schultz, who gave up poetry to write fiction, and then gave up fiction to return to poetry, next brings us a novel, a novel in verse. The Wherewithal (Norton; Feb. 3, 2014) collides the war in Vietnam with the 1941 Jedwabne massacre in Nazi-occupied Poland, through a son translating his mother’s diaries in a San Francisco basement. James Lasdun says of the novel, in its hybrid form,

As in his earlier work Schultz uses the resources of fiction, verse, and reportage to create something at once novelistic and deliriously poetic. It’s powerfully moving and disturbing both at the level of the small concrete details that form its basic building blocks and at the level of the larger decisions.

In a wonderful and rich 2008 interview with André Bernard for Five Points, Schultz speaks of his own earlier work and its use in “constant reassessing, weighing and deliberating of the past as a way of understanding the present.” He describes how writing—poetry—had to be covert; how it seemed to be in contradiction with survival, and the mores and parameters of his family:

I wrote poetry in a secretive way, I think, a secret from myself, I mean. I wrote it because it gave me great pleasure to do so and because it relieved the ever-building pressure of the demanding world around me. It's always served me as a way of appraising, and controlling overwhelming experiences. But this need, and desire, was always in conflict with my need to "survive." My father would've seen poetry, if he ever bothered to think about it, as self-indulgent.

And yet poetry—writing—is a way of visiting, revisiting, processing. Writing and reading, once sufficiently decoded and broken into salient parts, assist us in decoding the world. We need the urge to success; we need failure; need the tension between.

“Yes, indeed, this is the crucible of art,” Schultz replies to Bernard. “Every artist has his or her struggle to work out in their work. The more powerful the struggle, the more persuasive the art.”

Author Bio:

Kara Krauze is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.