Charles Bukowski’s Los Angeles

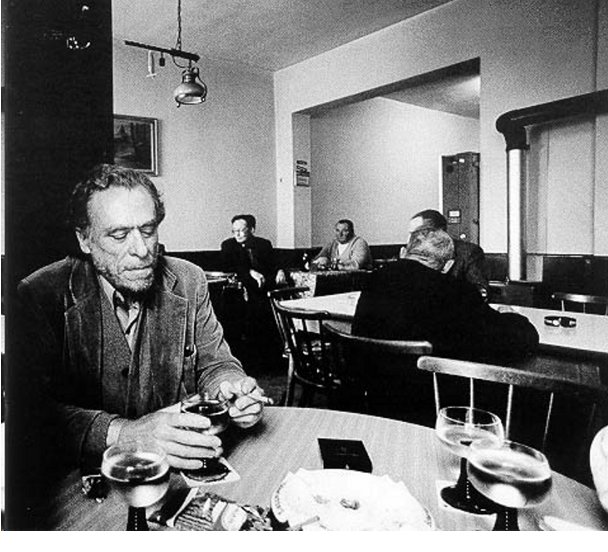

The creature who spoke from the bowels of society, the sovereign of booziness and grab‑ass who penned degenerate memoirs such as Post Office, Women, Factotum and Ham on Rye, was the voice of Los Angeles. Charles Bukowski lived and wrote in Los Angeles, a city whose name belies the makeup of its population. This big burly poet and the sordid Los Angeles of his novels stood against an image of movie stars, bleach blondes, hair plugs, bosoms pumped with silicon and lips with collagen.

What better place than here to depict how phony and evil and dangerous the struggle for beauty could be and, consequently, how the human light shines brightest from the gutters of existence? In a city of false angels, Bukowski proudly showed that he was without wings and utterly human. His writing suggested, however, that he was much closer to a sense of another world, whether the gateway to that world be at the bottom of a bottle of whiskey or on the receiving end of a left cross.

Born in Germany, Bukowski ultimately arrived in Los Angeles with his family in 1923 at the age of three and, for most of his 74 years of life, never left. Deeply entrenched in the city’s seedy underbelly, he fraternized with the lowest of men, finding difficulty in maintaining work and enduring a string of tumultuous relationships. Much of his best writing documents the common man’s struggle to get by, a plight he endured for the first 50 years of his life prior to gaining minor economic success and a cult following as a columnist, poet and novelist.

Bukowski once stated in response to the question of what makes a man a writer, “It’s simple, you either get it down on paper, or jump off a bridge.” Although certainly suicidal at times, Bukowski’s inclination toward the former is what separated him from his down‑and‑out peers. He wrote in his coming of age novel “Ham on Rye,” “sitting there drinking, I considered suicide, but I felt a strange fondness for my body, my life.”

In writing, he transcended the anonymity of the working-class man, revealed that even the everyday drunk or wrinkled two-bit hooker bore a spiritual depth as multifarious as any other American citizen. Work, whether conducted on the top floor of a high-rise office or deep within the galleys, was not an inherent duty or an honorable endeavor in itself, but rather this country’s method of stifling individuality and keeping the gears of capitalism’s death machine viciously turning. In “Ham on Rye,” Bukowski stated, “what were doctors, lawyers, scientists? They were just men who allowed themselves to be deprived of their freedom to think and act as individuals.”

Bukowski plodded through the gamut of soul‑sucking jobs, being fired from most, but in the process accumulating the experiences that would lead to many of his most important works. Steady employment for Bukowski came as a mail clerk at the Post Office Terminal Annex in downtown Los Angeles. The annex building, completed in 1940, was built in the Mission revival style and stands apart from the city’s more common architectural proclivities. Travel into the bowels of the building and you can almost smell the bureaucracy. Here is where one of America’s most important writers endlessly filed letters until his senses were numb from alphabetization. As a clerk, Bukowski would work in the evenings, leaving the daytime open for writing. The tasks of a mail clerk were degrading by nature, but were doubly so for Bukowski during the end of his tenure considering that he was also writing a column for the underground newspaper Open City entitled, “Notes of a Dirty Old Man.” He ultimately quit the post office to focus solely on his writing. He wrote in his 1971 novel “Post Office,” an autobiographical account of his time as a postal worker, “any damn fool can beg up some kind of job; it takes a wise man to make it without working.”

Immediately after leaving the post office, Bukowski sustained himself through a successful betting system at the horse tracks at Hollywood Park and Santa Anita. Hollywood Park race track will be closing operations at the end of the year, ending a 75-year run that saw some of racing’s most successful horses. Bukowski spent a great deal of his life here and, aside from the gambling, was able to observe man in his most desperate state. Here is where the true thirst for living radiated: at the brink of ruin. Bukowski saw that for many men, winning or losing was almost superfluous; the thrill was giving up of one’s self to chance.

At Santa Anita, I put 10 dollars on a horse named Vionnet to win, a long-shot at 15‑1. It was a Bukowski horse through and through. The general public was betting against her. Like many of the women in Bukowski’s life, this mare’s best days were behind her, and yet she was still holding on, fighting for life. She was difficult to lead into the gate, kicking when she got near, and it was obvious that her vitality had yet to be rubbed out completely by the knowledge and burden that comes with experience. Of all the horses, she was the greatest risk. You can imagine Henry Chinaski, the protagonist of Bukowski’s novels, sitting in the bleachers alone, betting what money he had left on this horse out of sentimentality or, better yet, a good old-fashioned hunch. For Bukowski, a man could be defined by the risks he was willing to take. Vionnet finished third out of seven horses.

Bukowski’s Los Angeles tour consists of many other locations, The Los Angeles Central Library and his bungalow home on De Longpre Avenue, to name a couple. He was a geographically rooted writer, drawing from and often assailing the city he lived in for the preponderance of his life.

But his kinship with the down‑and‑out and his international acclaim has made him a sort of patron saint of skid rows all over the world, a poet‑hero of the slums. He died in 1994 of Leukemia, but the human landscape he painted of this country’s poor remains as relevant now as it did almost 20 years ago. Travel to any skid row in America and you will find Bukowski’s Los Angeles.

Author Bio:

Steven Chandler is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

Photos: Marco Raaphorst (Wikipedia Commons); GIBride (Flcikr); Charles 16e (Flickr); Citoyen du monde (Flickr).