London Calling: Celebrating the City’s Street Photography

Photography 1860-2010

Dewi Lewis Publishing, 2011

$35.00

Prior to the 1950s, it was not uncommon to hear residents of London refer to their city as “The Smoke.” The nickname, a reference to the nubilous fallout from thousands of smoldering coal fires, was well earned.

A photograph of Charing Cross Road taken in 1937 by a young Wolfgang Suschitzky – which depicts hatted pedestrians disappearing into a wall of soot and fog – reflects perfectly the living conditions of the time. It was an environmental catastrophe in the making; and 13 years after that picture was made, the environment fought back with a vengeance. The Great Smog of 1952 – or “The Big Smoke” as it is sometimes called – lasted for five days and killed an estimated 12,000 people, prompting Parliament to pass a broad set of emissions regulations, including the Clean Air Act of 1956. They say a picture is worth a thousand words.

Suschitzky's photograph is one of 150 London street photos featured in the book London Street Photography 1860-2010 –which was published in the U.K. last year to compliment a touring exhibit of the same name. The exhibit closed last month at the Museum of the City of New York, but the book is still available through Dewi Lewis Publishing.

The collection features more than 70 photographers and spans three centuries – from the industrial revolution to the dawn of the information age – offering a glimpse of modern British history through the microcosm of life on its streets and avenues.

The images are all from the Museum of London, which only began officially collecting photography as art in 1979; and, while some notable names are missing (the recently resurrected Walter Joseph, whose body of work was acquired by the British Library, and the anonymous ‘80s-era guerilla photog “Johnny Stiletto” are two that come to mind) – and there are some temporal gaps (there is not a single photo depicting street life during the war years between 1940 and 1945, for instance) – what remains is a meaty and comprehensive historical record of the evolution of photography's purest form and the birth of a modern metropolis.

In a way, the term street photography is something of a misnomer; whether the mise-en-scene is a park, a boulevard, a cafe or a subway car, it's not streets we're interested in; it's people: People unencumbered by their own self awareness – people who are, quite simply, being human.

Even the earliest pictures, while clumsy by contemporary standards, reflect an authenticity of purpose, and it is evident from shots like Paul Martin's 1893 picture of a porter at Billingsgate Market and John Galt's “Cats' meat man” from 1902 that these early pioneers of street photography had already stumbled on the compelling human narrative that has kept the medium fresh and exciting in spite of its limited technical range.

Much of the clumsiness of these early shots was a function of technological limitation. By the turn of the century, however, advancements in camera design and commercially available roll film made it possible for photographers to wear what Dorothea Lange called a “cloak of invisibility,” injecting later pictures by Felix Man and the Russian emigre Cyril Arapoff with candidness and purity.

Once a receptacle for Parisian experimental runoff, by the 1940s London had earned its distinction as the summer capital of street photography (and a springboard to New York's coming ascendency), as artists like Suschitzky, Margaret Monck, Nigel Henderson, Roger Mayne, Lutz Dille, and countless unnamed photographers – several of whom are represented as “Anonymous” in London Street Photography – took to the avenue with their Leicas to capture the essence of their changing city and its shifting cultural paradigms. Along the way, the monochrome class distinctions that characterize the first half of the book give way to emerging cultural diversity and, with it, the introduction of color processing.

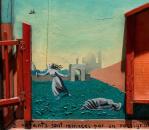

By the 1980s and 1990s, the vibrant melting pot of modern London comes alive in pictures like Keith Cardwell's “Sunday Market”, Sally Fear's “Chinese New Year” and Peter Marshall's 1991 “Shopkeeper.” More recently, young pioneers such as Nils Jorgensen, Adrian Fisk and David Gibson have been pushing the boundaries of the craft, exploring whimsical themes with an irony unique to this century.

Whether enjoyed as historiography, cultural expose, or a retrospective on the evolution of the craft, London Street Photography has something to offer both for those of us who spend their time behind the lens, and those who find themselves in front of it.

Author Bio:

Christopher Moraff is a contributing writer and photographer at Highbrow Magazine.