The Long and Necessary March to American Health Care Reform

Talk of the end of American exceptionalism seems to be everywhere lately, but in at least one area, the United States inarguably reigns supreme. Currently, per capita health care expenditures in the U.S. are approaching $8,000 a year, far more than anywhere else in the world. The nation with the second-highest per capita cost, Norway, spends $2,500 less per person per year. What do Americans get for their money? A life expectancy of 78.2 years, slightly ahead of Panama and Libya. By almost any measure, the planet’s richest country also has the least cost-effective health care system, delivering average treatment to most citizens at ridiculously high costs.

For millions of Americans, life-threatening illnesses mean not only painful treatment and medical uncertainty, but also the prospect of financial ruin. Without a guaranteed medical safety net for all citizens, serious medical diagnoses can mean bankruptcy, divorce, and foreclosure. Americans are certainly healthier than they were 100 years ago, but the improvements have come with a substantial cost. The longer life spans, better disease detection, and wider array of sophisticated treatment options that have improved life have all also substantially driven up costs and jeopardized the availability of treatment for millions.

So how could the nation that gave its citizens the G.I. Bill and Social Security, leave millions uninsured, at risk, and dangerously unhealthy?

Minnesota Congresswoman and Tea Party darling Michelle Bachman once claimed, “There are people who just decide they want to roll the dice and take their chances that they won’t need insurance.” Her statement was widely derided but, oddly enough, spoke to a fundamental problem with our current health care system. Younger Americans simply don’t suffer the heart attacks, strokes, and osteoporosis that drive older Americans to the doctor. Workers just entering the labor market, who often don’t receive health coverage through work, could make the rational decision to spend their scarce dollars on other basics like food and rent, rather than insuring themselves against risks that probably won’t materialize anytime soon. Indeed, the Kaiser Family Foundation found 28 percent of Americans between 26 and 34 were uninsured in 2010.

Additionally, workers who can’t afford health coverage on their own and who don’t have the kind of stable jobs that provide it, may have little choice but to live without insurance. These workers often have no choice but to put off treatment when signs of medical trouble surface, hoping to save a few bucks on doctor visits when the problem goes away. Indeed, despite Bachmann and other conservatives’ rosy vision of carefree youths gallivanting about without insurance, a 2007 Kaiser Family Foundation report found that working families make up 80 percent of those without health insurance.

When the uninsured are unable to pay out of pocket for preventive care and later need treatment, they become emergency room patients. This is more than just a human tragedy, since the country as a whole subsidizes those who have to turn to emergency care when they can’t afford anything else. These costs become absorbed by society as a whole, including the insured, thanks to a Reagan-era law known as the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA).

Since the passage of the EMTALA in 1986, emergency rooms accepting federal funds have been required to stabilize patients, regardless of their ability to pay. Originally intended as the “Patient Anti-Dumping Act,” this presumably well-intentioned law has created a bizarre, expensive, and rigid requirement that emergency rooms provide treatment to those who can’t pay for it. Therefore, today, the poorest Americans are given a very basic level of health care, but rather than have access to the kind of prevention that might keep them healthy and out of emergency rooms, they end up requiring urgent care, run up huge bills, and when they are unable to pay, the rest of the country is stuck with the check.

The number of uninsured Americans at risk of falling through the cracks in this way has only swollen in recent years. A Gallup poll found that from January 2008 to December 2011, the ranks of the uninsured swelled from just under 15 percent to close to 18 percent. One proven solution to this problem is to have everyone pitch in and provide a basic health care safety net for all. When a citizen needs help, they can turn to a system that receives support from everyone, and when healthy, said citizen can contribute until they require help once again.

Countries such as Germany began experimenting with this type of compulsory insurance system, a precursor to universal coverage, as early as 1883. Other European governments, such as those of Sweden and France, opted to subsidize worker-formed “mutual benefit societies,” which operated under the principle of mutual defense against the illness of the sick. While the U.S. relied on states to set health care policy during this period, the burgeoning American progressive movement began calling for a national health care policy.

Fans of AMC’s Mad Men should appreciate the AMA’s contribution to the health care debate lexicon, which came around Teddy Roosevelt’s time. According to historians, the group conjured the loaded term “socialized medicine” in the early 1900s. The phrase would often be deployed against efforts for universal health care in the coming years, along with other clever forms of fear-mongering.

When anti-German fears of the “Prussianization of America” rose up in the wake of World War One, the opportunity to assure universal health care early in the 20th century was lost, according to Jill Lepore in an article in the New Yorker. Opponents used anti-German fear to block reform at both the national and state level, defeating a constitutional amendment designed to guarantee universal coverage in California by telling voters that universal health care was “Born in Germany” and asking “Do you want it in California?” The pamphlet asked this question right next to a picture of the Kaiser.

In the decades during and after World War Two, national health reform efforts lost steam. As the county geared up for and fed the war effort, demand for labor exploded just as young, male workers were sent overseas. Government controls prevented companies from offering higher salaries, and to attract valuable workers remaining stateside, employers offered full medical coverage at rock-bottom prices. During World War Two, workers received care from company clinics at Henry J. Kaiser’s California shipyards for a mere 50 cents from every paycheck. No doubt the doctors’ offices of years ago were very different from those of today. Without digital scans, ultrasound, and a menu of other fancy testing and treatment options, medical coverage remained a relatively inexpensive way for employers to keep their workers content and on the job.

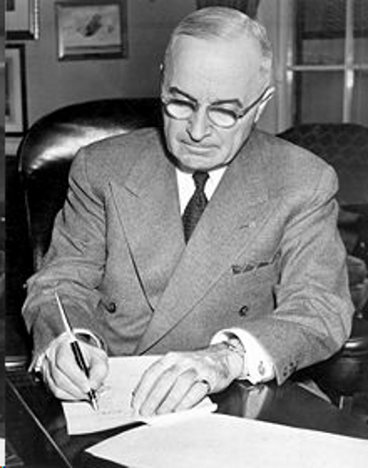

Once again, using the ominous-sounding “socialized medicine,” opponents of reform scared off Franklin D. Roosevelt when he considered adding a health benefit to Social Security around this time. Fear remained an effective tool for blocking efforts to expand coverage on a national level in the decades during and after World War Two. When Harry Truman championed a comprehensive health care system in 1945, opponents went back to the “fear of socialism” well to kill the plan. Engaging in the kind of hyperbole that has become a hallmark of the health care debate, Republican Robert Taft declared Truman’s proposal “the most socialistic measure this Congress has ever had before it.”

The Republican Party would once again employ fear of the Soviet lifestyle against reform when liberals looked to guarantee health care for the elderly. In 1961, Ronald Reagan warned “it’s very easy to disguise a medical program as a humanitarian project; most people are a little reluctant to oppose anything that suggests medical care for people who possibly can’t afford it." The American Medical Association (AMA) spread Reagan’s words by distributing vinyl records with the Gipper’s dire predictions. Despite Reagan’s dark forecast that "pretty soon your son won't decide when he's in school, where he will go, or what he will do for a living," Congress soon extended Social Security to cover health insurance for the elderly, later known as Medicare.

When an accomplished, Yale-educated first lady entered the White House in 1993, right-wing paranoia found a target almost as inviting as the Soviet Union. It was a less than warm welcome for the debut of the Clinton health care package that year. The plan, which would have provided options for every citizen to choose among private plans, sparked outrage. "It was too big, too complex, too government," according to Newt Gingrich, looking back on the plan after he had left the House. In fact, many of the elements have been praised by experts, and its failure was largely due to a well-orchestrated effort from Republicans and the health insurance industry. Once again the AMA was there on Hillary Care, contributing $3 million to help derail the plan.

When President Barack Obama entered the White House in 2009, one of the first tasks he took on was the U.S. health care system. The plan the administration devised addressed the most basic problem with U.S. health care, ensuring that the vast majority had care, that nearly everyone pitched in by buying insurance (with subsidies for the very poor), and that in exchange for massive new business insurance, companies could no longer discriminate against those with pre-existing conditions. Because the government was prevented from competing with private companies, the United States will still be short of the care provided by other countries, but it is a solid step towards matching the rest of the developed world.

With the Supreme Court poised rule on the constitutionality of Obama’s Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act -- including the critical health insurance mandate, a basic mechanism to ensure the whole country contributes to a more predicable and fair program than our current haphazard system --the future for American health care reform remains uncertain.

Author Bio:

Matthew Rudow is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.