The Serious and the Smirk: The Smile in Portraiture

This is an excerpt from an article [The Serious and the Smirk: The Smile in Portraiture] originally published in The Public Domain Review under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. If you wish to reuse it, please see: https://publicdomainreview.org/legal/

Today, when someone points a camera at us, we smile. This is the cultural and social reflex of our time, and such are our expectations of a picture portrait. But in the long history of portraiture, the open smile has been largely, as it were, frowned upon.

In Charles Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby (1838-39) the portrait painter Miss La Creevy ponders the problem:

…People are so dissatisfied and unreasonable, that, nine times out of ten, there’s no pleasure in painting them. Sometimes they say, “Oh, how very serious you have made me look, Miss La Creevy!” and at others, “La, Miss La Creevy, how very smirking!”… In fact, there are only two styles of portrait painting; the serious and the smirk; and we always use the serious for professional people (except actors sometimes), and the smirk for private ladies and gentlemen who don’t care so much about looking clever.

A walk around any art gallery will reveal that the image of the open smile has, for a very long time, been deeply unfashionable. Miss La Creevy’s equivocal ‘smirks’ do however make more frequent appearances: a smirk may offer artists an opportunity for ambiguity that the open smile cannot. Such a subtle and complex facial expression may convey almost anything — piqued interest, condescension, flirtation, wistfulness, boredom, discomfort, contentment, or mild embarrassment. This equivocation allows the artist to offer us a lasting emotional engagement with the image. An open smile, however, is unequivocal, a signal moment of unselfconsciousness.

Such is the field upon which the mouth in portraiture has been debated: an ongoing conflict between the serious and the smirk. The most famous and enduring portrait in the world functions around this very conflict. Millions of words have been devoted to the Mona Lisa and her smirk – more generously known as her ‘enigmatic smile’ — and so today it’s difficult to write about her without sensing that you’re at the back of a very long and noisy queue that stretches all the way back to 16th century Florence.

But to write about the smile in portraiture without mentioning her is perverse, for the effect of the Mona Lisa has always been in its inherent ability to demand further examination. Leonardo impels us to do this using a combination of skillful sfumato (the effect of blurriness, or smokiness) and his profound understanding of human desire. It is a kind of magic: When you first glimpse her, she appears to be issuing a wanton invitation, so alive is the smile. But when you look again, and the sfumato clears in focus, she seems to have changed her mind about you. This is interactive stuff, and paradoxical: the effect of the painting only occurs in dialogue, yet she is only really there when you’re not really looking. The Mona Lisa is thus, in many ways, designed to frustrate — and frustrate she did.

The hubbub around her smile really got going in the 19th century, when unfettered critical devotion to Renaissance art was at an all-time high. One critic and historian in particular, Jules Michelet, enjoyed, or at least endured, a very personal moment with her. In Volume VII of his Histoire de France (1855) he wrote, ‘This canvas attracts me, calls me, invades me. I go to it in spite of myself, like the bird to the serpent.’

Artfully concealed under the guise of Romantic criticism, this was in fact an expression of the new cult of the Mona Lisa, and over the years historians would attempt to outdo each other with their devotion to her charms. Michelet’s son-in-law Alfred Dumesnil, also a critic, went even further in his L’art Italien, as if locking antlers with his in-law: ‘The smile is full of attraction, but it is the treacherous attraction of a sick soul that renders sickness. This so soft a look, but avid like the sea, devours.’

In England, John Ruskin asserted that it was a merely a ‘caricature’, to which a young Oxford don named Walter Pater responded in his Renaissance: ‘All the thoughts and experience of the world have etched and moulded there… the animalism of Greece, the lust of Rome, the mysticism of the middle age with its spiritual ambition and imaginative loves, the return of the Pagan world, the sins of the Borgias…’

Things came to a head in 1919 when the French artist Marcel Duchamp triumphantly created his version, augmenting the smile with a fancy moustache and titling it L.H.O.O.Q., which only exacerbated things in rascally Dadaist fashion. (L.H.O.O.Q. translates phonetically as ‘she has a hot arse’, but also relates to an idiomatic expression of ‘fire down below’.) For Jules Michelet, she may have been the object of romantic love: For Duchamp, she was the object of spirited masturbation.

It remains a commonly held belief that for hundreds of years people didn’t smile in pictures because their teeth were generally awful. This is not really true – bad teeth were so common that this was not seen as necessarily taking away from someone’s attractiveness. Lord Palmerston, Queen Victoria’s Whig prime minister, was often described as being devastatingly good-looking, and having a ‘strikingly handsome face and figure’ despite the fact that he had a number of prominent teeth missing as a result of hunting accidents. It was only in later life, when he acquired a set of flapping false teeth, that his image was compromised. His fear of them falling out when he spoke led to a stop-start delivery of his speeches, causing Disraeli to openly poke fun at him in Parliament.

Nonetheless, both painters and sitters did have a number of good reasons for being disinclined to encourage the smile. The primary reason is as obvious as it is overlooked: It is hard to do. In the few examples we have of broad smiles in formal portraiture, the effect is often not particularly pleasing, and this is something we can easily experience today. When a camera is produced and we are asked to smile, we perform gamely. But should the process take too long, it takes only a fraction of a moment for our smiles to turn into uncomfortable grimaces. What was voluntary a moment ago immediately becomes intolerable. A smile is like a blush – it is a response, not an expression per se, and so it can neither be easily maintained nor easily recorded.

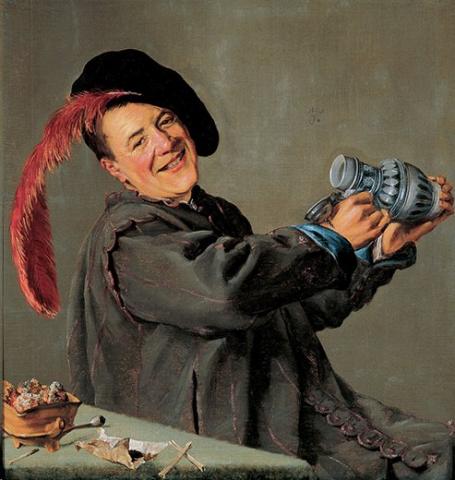

Smiling also has a large number of discrete cultural and historical significances, few of them in line with our modern perceptions of it being a physical signal of warmth, enjoyment, or indeed of happiness. By the 17th century in Europe, it was a well-established fact that the only people who smiled broadly, in life and in art, were the poor, the lewd, the drunk, the innocent, and the entertainment – some of whom we’ll visit later. Showing the teeth was for the upper classes a more-or-less formal breach of etiquette. St. Jean-Baptiste De La Salle, in The Rules of Christian Decorum and Civility of 1703, wrote:

There are some people who raise their upper lip so high… that their teeth are almost entirely visible. This is entirely contradictory to decorum, which forbids you to allow your teeth to be uncovered, since nature gave us lips to conceal them.

Thus the critical point: Should a painter have persuaded his sitter to smile, and chosen to paint it, it would immediately radicalize the portrait, precisely because it was so unusual and so undesirable. Suddenly the picture would be ‘about’ the open smile, and this is almost never what an artist, or a paying subject, wanted.

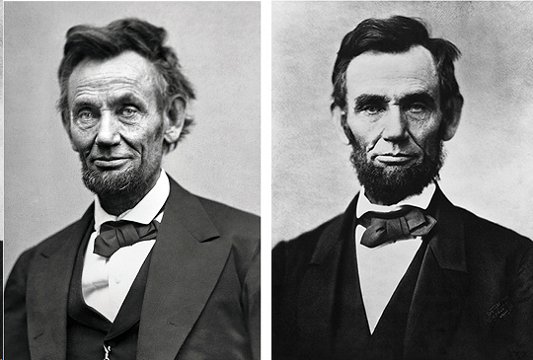

In this sense, a portrait was never so much a record of a person, but a formalized ideal. The ambition was not to capture a moment, but a moral certainty. Politicians were particularly sensitive to this. For a more modern, photographic example of the principle, we may consider Abraham Lincoln. Here was a man better known than most, in his day, for his sense of humor, there being a number of well-known stories about him regularly drawing hoots of laughter from those in his company. While there are some informal images of him looking distinctly avuncular, a wit doesn’t abolish slavery without tough critical opposition, and in his best-known image, the ‘Gettysburg portrait’, he takes on the gravest expression imaginable. So powerful are these images that this is how he is generally remembered today. Mark Twain, a contemporary of Lincoln’s, was firm on the matter in a a letter to the Sacramento Daily Union:

A photograph is a most important document, and there is nothing more damning to go down to posterity than a silly, foolish smile caught and fixed forever.

Author Bio:

Nicholas Jeeves is an artist, writer, and lecturer at the Cambridge School of Art.

This is an excerpt from an article [The Serious and the Smirk: The Smile in Portraiture] originally published in The Public Domain Review under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. If you wish to reuse it, please see: https://publicdomainreview.org/legal/

Image Sources:

Judith Leyster’s Jolly Toper (1629) – Source.

Marcel Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. (1919) – Source (NB. Only public domain in the U.S.)

Two photographs of President Lincoln by Alexander Gardner. Left: Taken in 1865 – Source. Right: Taken in 1863 – Source.

Left: John Singer Sargent’s study for Miss Eleanor Brooks (1890) – Source. Right: Detail from the finished painting (1890) – Source.

Highbrow Magazine