Nothing in Common: One Small Step for Jon Stewart, One Giant Leap for the Left

Edward R. Murrow’s famed “Good Night, and Good Luck” broadcast—a scathing éxpose of Senator Joseph McCarthy capped with Shakespearean verse—is the archetype for media-based confrontation and virtually unimaginable when viewed through the lens of today’s complex media landscape. The event stood so fatefully on the precipice of history that Murrow, who was torn over using his hallowed news program for editorial purposes, nearly collapsed after he signed off the air.

His critique was viewed as an overwhelming success: CBS News headquarters was flooded with thousands of supportive telegrams and phone calls. The maneuver was among the catalysts behind the downfall of McCarthyism and cemented Murrow’s legacy in the pantheon of broadcasters, regardless of medium or genre.

It is difficult to foresee a media moment being so pure again. The victory, especially when viewed from today’s perspective, was monumental. The combatants, prototypes of good and evil: the reluctant purveyor turned activist, as a Murrow biographer described him, clashing against the fear monger, the zealot who put a nation’s patriotism on trial.

The way media and news programming have evolved, no confrontation could ever be so simple and so sweeping again. Confrontational commentary is now the status quo, the pillar of cable news programming, a necessary and thus contrived component. It piques attention. It arouses fear, hate, political tribalism—the easiest sentiments to tap into, manipulate and bring the viewer back for more. Theatrics must then supersede all else --it makes for better television-- easily packaged feuds that, if amply polarizing, can go viral on the Internet and beckon its factions of viewers to tune in anon.

Most importantly, the victories to be had, if any, are small and always in the eye of the beholder. Cable news audiences are too deeply aligned to actually be swayed. Those undecided are left to reconcile the indecipherable remnants of shtick, obfuscation and pure noise.

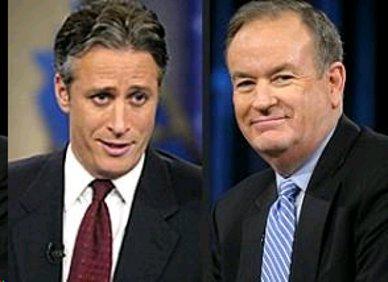

When comedian Jon Stewart appeared on the O’Reilly Factor, as he did this past May, to debate Bill O’Reilly, it was to be a battle of two men considered archetypical of their political allegiances. The debate stemmed from the rap artist Common being asked to a White House poetry slam despite having sympathized and visited with Joanne Chesimard, a.k.a. Assata Shakur, who was convicted of killing a NJ State trooper in 1973.

O’Reilly believed that by inviting Common to the White House, the president thereby validated and undeservedly elevated Common’s stature as a musician. It is the duty of the president, O’Reilly said, to look at an invitee’s resume and determine that he is virtually “unimpeachable.” Honoring the killer of a law-enforcement officer patently failed in meeting this expectation.

Stewart believed that Fox, as a network, had overblown the connection between Common and Chesimard. He is deeply bothered by Fox News’ lack of consistency in reporting and fabricating divisive cultural issues; a tacit accusation of network-wide racial insensitivity. He veils this accusation in his use of the phrase “selective outrage machine,” the implication being that if Common and the president were both white men, Fox probably would have overlooked the incident entirely.

Though Stewart considers himself comedian first and political satirist second, he is clearly on a mission when he steps onto a set at Fox News. As Edward R. Murrow believed that Senator McCarthy’s bullying and fear tactics posed a grave threat to the nation, Stewart, like other voices from the left, fears that the conservative media’s, namely Fox News’, presentations of opinion under the guise of fact is irreparably poisoning the nation’s political discourse. The late David Foster Wallace described the phenomenon as:

“...a peculiar, modern, and very popular type of new industry, one that manages to enjoy the authority and influence of journalism with the stodgy constraints of fairness, objectivity and responsibility that make trying to tell the truth such a drag for everyone involved.”

In his battle for a small victory, Stewart must first overcome several obstacles just to enjoy a stalemate. O’Reilly, a skilled debater, , is not only extraordinarily well-versed in verbal repartee, but he is also quite physically imposing. Standing six feet, four inches tall, his presence onscreen is impressive.

O’Reilly is also known to slip behind a self-satirical shield, characterized by a tinge of ironic detachment. This allows him to argue particularly outrageous points without having to be held completely accountable for them. Borrowing a term O’Reilly used in the Common debate, this duplicity of self allows him to “pettifog” an argument beyond what can be reasonably repaired in a five-minute segment. Lastly, he holds a trump card against any morally or intellectually nuanced argument that Stewart will attempt to proffer. He can paint the comedian as un-American—a tactic out of the McCarthy playbook—or as an elitist.

The cogency of Stewart’s argument, however, fleetingly takes O’Reilly by surprise. He came to The Factor armed with several historical examples where musical artists had written songs honoring convicted killers—Bono, Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen—only to have been invited to the White House. In spite of what can probably be estimated as the superior argument, Stewart still vacillates between the roles of comic foil, halcyon logician, and incensed activist. To even have an opportunity to accomplish his objective, Stewart is sure to be elusive in his inflammation, intelligence or even seriousness at the risk that O’Reilly will marginalize him entirely by labeling him as such.

Stewart knows that by showing up he will win the hearts of leftists and the lion’s share of centrists. But his real objective, the sole reason he went onto his competitor’s program and enemy network and willingly boosted their ratings for the evening, is to somehow poke the minutest pinhole into the O’Reilly caricature. He’s fighting for the sliver of a moment where he can give the staunchest O’Reilly supporter a peek behind the Fox News curtain and force them to question, however fleetingly, if his message is genuine or if it’s just one big show.

The effort is thwarted by the better portion of the debate. The legs of a sound argument were, for the part, undercut by sheer O’Reilly attitude and tendency to hone in on technicalities. Stewart put forth three instances apparently analogous to Common’s; The Factor host vociferated the distinction that Common had actually visited Chesimard, pushing this case “beyond a reasonable doubt.” Stewart then turned indignant, calling the Fox News “apparatus” as an “infection machine;” O’Reilly shrugged the attack off with an ironic quip, “You mean the diverse opinions that we have here.”

Then something happened that can only be equated to two actors breaking the fourth wall. Stewart stepped out of his role of debater, comedian, activist, and addressed O’Reilly as he might when the cameras are off. “I like you as well,” Stewart said, “It saddens me to see you wasting your time.”

The sincerity of the statement penetrated the commentator’s cloak of pomp and chicanery. For an instant, he ever so slightly flapped his arms and attempted a quick, but awkward transition (“All right, now”). O’Reilly was about to shuffle his papers but thought better of it. For that moment, his mask was off and you could imagine him telling Stewart that this is the way things have to be.