Louie, Breaking Bad, and the Rise of Quality Television

It’s no secret that the summer television season isn’t exactly high quality. It’s typically a time for major networks to dump shows that were, for one reason or another, deemed sub par for a slot in their regular season lineup or to air reality shows and competitions that cost very little to produce-- which is why you end up with shows like Combat Hospital, an import from Canada, showing up on ABC’s primetime schedule, or competition shows like So You Think You Can Dance? airing multiple times in a given week.

All is not lost, however. In the last decade, it’s the cable and premium channels that have carved out their own niches of quality shows even in the “summer graveyard” season. Networks like HBO, AMC, and FX have been bucking convention for years in the choices they make and risks they take, and putting out high-caliber products year-round is just another gamble that has paid dividends.

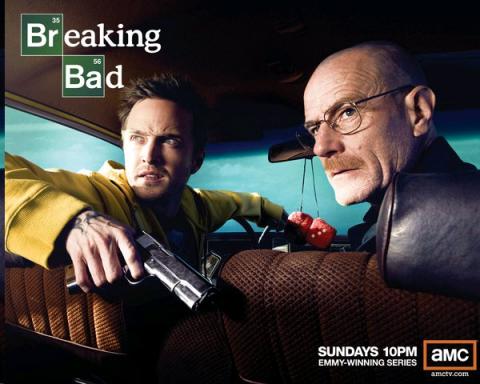

Look no further than two of the most-anticipated and talked-about shows: AMC’s Breaking Bad and FX’s Louie. The former is a drama about a high-school chemistry teacher named Walter White (Bryan Cranston) who finds out he has terminal lung cancer and decides to begin cooking crystal meth in order to leave his family a nest egg. The latter is a comedy about Louis C.K.’s fictionalized life as a single father living in New York City. Yet each can stake claim as being the preeminent show in their respective genres, and both, despite being very different on the surface, have a similar disregard for convention that makes them unique, rewarding viewing experiences.

As viewers, we expect certain things to come at a certain pace in a television show: romances play out slowly with stolen glances and kisses, villains are typically dealt with over the drawn-out course of a season. Shows can always play with these conventions in new and interesting ways, but rare is the one that discards them altogether.

Breaking Bad has made this one of its trademarks. The very nature of the show is unconventional. It asks us to care about a character who turns from hero to villain right before our eyes. Walter White starts as a milquetoast high-school teacher who wants to secure his family’s future, but he eventually becomes a murderer and a drug lord, someone who keeps digging himself deeper even when he’s earned enough money. Anti-heroes are rampant on the big and small screens, but Walter goes beyond this into actual villainy, willingly dragging his loved ones down with him. Breaking Bad is a show with a very palpable sense of good and evil, and the more we watch, the more it tests our own dogmas on the subject.

The show also refuses to pace itself in the way that other crime dramas have in the past, letting plot points come at a breakneck pace that both catches viewers off-guard and remains true to the groundwork the show has already laid. Last season, the show’s third, introduces us, in the opening scene of the first episode, to two twin cartel killers who seek to kill Walter. They’re typical cinematic villains, unflinchingly violent, yet we have built-in expectations about their character arc. We aren’t particularly worried about them yet, because we know that, based on other shows we’ve seen, they won’t cross paths with the main character until much later in the season, likely in the season finale. However, by the end of the second episode, they’re inside Walt’s house with an axe, waiting for him to get out of the shower so that they can murder him. Even though we understand that there will be no show without the main character, still our rhythm as spectators is thrown off, which only serves to draw us in further.

Louie has just as much disregard for normality, and is all the stronger a show for it. The basic premise of an episode is simple: a series of vignettes linked by clips of C.K.’s standup act. What he does with that setup is anything but basic. Some episodes are strictly comedic, others veer into more dramatic and surreal territory. FX gives him complete creative control (he writes, directs, stars in, and even edits each episode himself). In one of the standout episodes of last season, C.K. is humiliated by a high-school-aged bully while out on a date, then decides to follow the young man home. He then confronts the bully’s parents, whose shrill and abusive tendencies make it obvious why their son turned out how he did. It’s a sequence that delves into squeamish, discomforting humor, but nothing worse than one would see on an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm or The Office. When the father joins C.K. on the front porch to share a cigarette and discuss how difficult it is to be a parent, the scene veers quickly into poignant drama, wearing a hopeful heart on its sleeve in a way no other comedy on television could replicate.

Another unique aspect of Louie is its occasional lapse into bizarro surrealism. Comedies, by nature, are cartoonish and bizarre; the worlds of Greendale Community College in Community and Pawnee, Indiana in Parks and Recreation are essentially live-action cartoons. The New York City of Louie, though, is different. Sometimes, it’s a normal place where people can have family conversations over dinner. Other times, it’s a place where homeless men are kidnapped and replaced by other homeless men, or where cab drivers fight each other with tire irons for the right to pick up a fare. We’re never sure if what we’re seeing is really happening or is just a daydream or metaphor in C.K.’s head, but these asides lend the show a peculiar lightness, one that perfectly captures the sense of melancholy that comes with living in the big city.

Programs like Breaking Bad and Louie that will change your perception of what the entire storytelling medium is capable.

Author Bio:

Andrew Cothren is a Brooklyn-dweller whose short fiction has been published or is upcoming in Eleven Eleven, The Legendary, and Drunken Boat. More of his work can be found at andrewcothren.com.