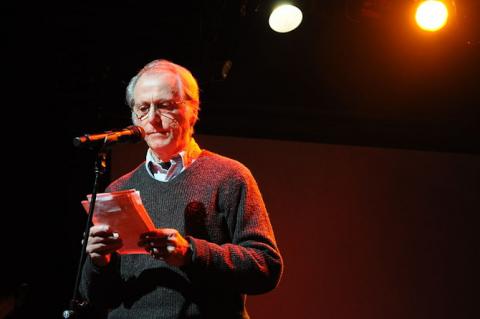

Don DeLillo Stories Offer Terror and Dread in Captivating Prose

The Angel Esmeralda: Nine Stories

Don Delillo

Scribner

211 pages

The nine stories in The Angel Esmeralda appear in three sections, roughly corresponding with what might be called Early, Middle and Late DeLillo. The early period extends from his first novel, Americana, to the spell-binding and prophetic novels Players and Running Dog. Middle DeLillo includes White Noise, his National Book Award winner, and Libra, about the Kennedy assassination, perhaps his single most accomplished work. This rich period culminates in Underworld, the long, masterful and muddily transcendent epic.

Late DeLillo, where we find ourselves now, has generated a series of elliptical works like Cosmopolis and Omega Point. The short novels of Late DeLillo, written since September 11, 2001, seem to fold in on themselves, as if the author wishes to use as few words as possible to communicate his vision to us.

Reading the stories in The Angel Esmeralda, therefore, reminds us how varied, adept, intelligent and ruthlessly honest this great writer has been from the beginning. Like his novels, each of these stories trades in dread and terror, and our failure to connect in the fractured and chaotic past half-century.

“Human Moments in World War III,” for example, describes the narrator’s inability, while orbiting the earth in a “recon-interceptor,” to fathom the thinking of his fellow astronaut:

“Vollmer has entered a strange phase. He spends all his time at the window now, looking down at the earth. He says little or nothing. He simply wants to look, do nothing but look. The oceans, the continents, the archipelagos … He takes meals by the window, does checklists at the window, barely glancing at the instruction sheets as we pass over tropical storms, over grass fires and major ranges. I keep waiting for him to return to his prewar habit of using quaint phases to describe the earth: it’s a beach ball, a sun-ripened fruit. But he simply looks out the window, eating almond crunches, the wrappers floating away.”

Other stories depend on fleeting, and deeply unsettling, encounters—a man jogging in the park sees, or thinks he sees, a child’s abduction (“The Runner”), a woman brings a man home from a museum exhibit and suddenly faces the specter of sexual violence (“Baader-Meinhof”). A growing sense of dread overlays nearly every page, dread of “the world out there, little green apples and infectious disease.” However bad things have been, these stories say, it will only get worse.

It’s rare when a novelist’s private vision so precisely anticipates a transformational public event. The horror of 9/11 was in the DNA of DeLillo’s prose at least since Players (1977), in which a young couple’s marriage founders on the frenzy of New York life and a terrorist killing on the floor of the Stock Exchange. Running Dog (1979), the novel that followed, was an unnervingly fast-paced and literate thriller involving a transvestite murder victim and the ferocious hunt for a home-movie shot in Hitler’s bunker. It, too, offered a visionary paranoia unlike anything else in contemporary literature. These two largely unheralded masterworks caught early on the pain and dread throbbing in our bloodstream, caused by modern times.

In “Creation,” the first story in The Angel Esmeralda, another young couple seeks to catch a flight off an unnamed West Indies island. Days pass, flights are either overbooked or fail to materialize, and soon panic sets in. The couple’s exchange is characteristic of DeLillo’s uncanny gift for sputtering rapid-fire dialogue:

“We’ll get out. If not at six-forty-five, then late in the afternoon. Of course, if that happens, we miss our connecting flight in Barbados.”

“I don’t want to hear,” she said.

“Unless we go to Martinique instead.”

“You’re the only man who’s ever understood that boredom and fear are one and the same to me.”

“I try not to exploit that knowledge.”

“You love to be boring. You seek out boring situations.”

“Airports.”

“Hour-long taxi rides,” she said.

What happens after Jill manages to escape the island spins the narrative off in unexpected ways. It’s among the most harrowing and affecting stories in this collection.

The title story centers on the efforts of an elderly nun, Sister Edgar, to care for the unfortunate souls adrift in the South Bronx in the 1990s. When a 12-year-old homeless girl is raped and murdered, her apparition miraculously appears to a crowd of the faithful on a billboard advertising Minute Maid Orange Juice. Sister Edgar’s reaction provides a tiny ray of hope in DeLillo’s fictional universe of hopelessness and isolation:

“Everything felt near at hand, breaking upon her, sadness and loss and glory and an old mother’s bleak pity and a force at some deep level of lament that made her feel inseparable from the shakers and mourners, the awestruck who stood in tidal traffic—she was nameless for a moment, lost to the details of personal history, a disembodied fact in liquid form, pouring into the crowd.”

The Angel Esmeralda, DeLillo’s first collection of short fiction, perfectly captures our free-floating dread of the world around us, and why it makes good sense to feel that way. These stories are an excellent introduction to the work of our most compelling living American novelist.

Author Bio:

“Death Threat,” an excerpt of Lee Polevoi’s new novel, The Confessions of Gabriel Ash,appeared recently in Highbrow Magazine.

Photo credit: Thousand Robots (Wikimedia.org, Creative Commons)