The American Dream and Ideology in the Road Runner Cartoon

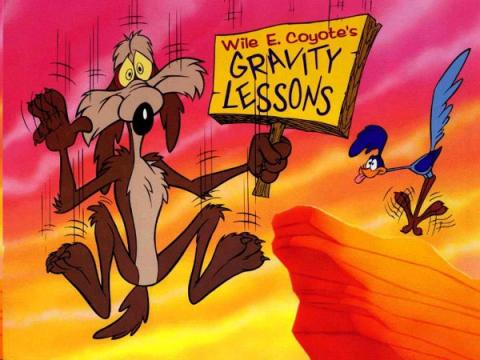

The premise of the Road Runner/Wile E. Coyote cartoon is that of a nature show, an organism attempting to satisfy its biological needs. Struck with hunger, Wile E. Coyote goes out into the world, tracks and chases down his food. However, he does not possess the proper physical attributes to catch his prey, the Road Runner -- he is simply not fast enough. The gimmick is that he acquires some tools, machines, whatever may be at his disposal, in order to make up for this lack. The joke on Wile E. Coyote is, much to the amusement of the spectator, the technologies fail, resulting in his numerous, and at times gruesome, “deaths.”

While the plot certainly goes under many different configurations, it is starkly repetitive: The same roles are occupied and performed. For contrast, Bugs Bunny or Mickey Mouse go on different adventures, occupying different character roles, sometimes a sailor, a cowboy at others. So despite the redundancy, what intrigues the viewer?

The pragmatic answer would be that the humor is drawn from the different kinds of instruments Wile E. Coyote uses, the increasing grandiosity of those technologies, the different forms of deaths he undergoes, the necessary physical exaggeration of the actions due to a lack of dialogue, and so on. But rather than taking this cartoon as mere entertainment for the family, it also raises important issues lying in the heart of the unease in our culture.

Douglas R. Bruce of John Carroll University, in a 2001 paper (“Notes Towards a Rhetoric of Animation: The Road Runner as Cultural Critique” Critical Studies in Media Communication 18.2, 2001), contends that the Roadrunner cartoon criticizes America’s over-reliance on technology through a retelling of the Myth of Sisyphus. As the story goes, Sisyphus, due to his hubris against the gods, is sentenced to roll a large boulder up a hill, only to have it fall down the hillside upon reaching the top, for eternity. Americans and the coyote are similarly condemned to search for and develop ever-more grandiose mechanisms to fulfill basic needs. This absurd condition is resolved by a return to the wild for the coyote, as Professor Bruce claims the former “could catch his prey without assistance.” For Americans, it would be to abandon this quest to dominate nature through technological prowess.

This reading of the cartoon is unsatisfactory in its overestimation of the coyote’s and Americans’ abilities. It assumes that needs can be met without the implementation of technologies, done so in a ”natural” way. This criticism is perhaps best viewed through a discussion of the social contract, the hypothetical agreement between independent persons regarding schemes of cooperation towards the construction of a society, a frame of reference popular among philosophers from the Enlightenment on to discuss the nature of rights, legitimate government, and justice. The coyote’s position is analogous to each person implicated in the social contract.

As some would have it (Hobbes, Leviathan, 1651), one enters into the social contract for mutual advantage. That is, each person derives benefit from cooperation, as fulfilling certain needs is rendered impossible without it. The motive of the coyote’s inability to catch the roadrunner from his own prowess induces an embrace of society.

The indebtedness to social contract theories is apparent in the Preamble to the U.S. Constitution, which enumerates those benefits to be conferred upon each citizen. As such, these benefits are to be viewed as obligations that the government must fulfill to the people it governs. And yet, in the cartoon, these obligations to the coyote are not met. Despite his attempts, the coyote is nowhere closer to satisfying his needs than when he started, and in fact may be worse off.

The political gesture performed by the Roadrunner cartoon calls into question the degree to which a society in fact fulfills its obligations to its constitutive members. For a concrete example, the American Dream is the promise of a materially comfortable life in exchange for hard work. Isn’t this threatened dream the flag under which the various Occupy movements have rallied? At first sight, then, the moral of the story is also a call to return to the wild: the promotion of anarchy. If a society cannot fulfill its duties to the citizen, he should leave the protection of the city, (lest he throw himself from the cliffside).

The more radical interpretation, however, would be to couch the show within the broader context of the culture industry. In their 1947 work, Dialectic of Enlightenment, German critical theorists Max Horkheimer and Theodor Adorno argue that the culture industry, rather than docilely providing the masses with entertainment, is in fact a new form of ideological control for the 20th century, one socially emerging from the confines of religion and “pre-capitalist residues.”

The Roadrunner cartoon functions as a form of ideological control in its aforementioned act of repetition. This recurrence of the coyote’s death serves as a reminder that those with access to economic, political, and cultural power have zero interest in fulfilling their obligations to the social contract, and that we should accept these corrupted provisos out of a misguided faith in the Protestant Work Ethic. To quote Horkheimer and Adorno:

“To the extent that cartoons do more than accustom the senses to the new tempo, they hammer into every brain the old lesson that continuous attrition, the breaking of all individual resistance, is the condition of life in this society. Donald Duck in the cartoons and the unfortunate victim in real life receive their beatings so that the spectators can accustom themselves to theirs… The culture industry endlessly cheats its consumers out of what it endlessly promises. The promissory note of pleasure issued by plot and packaging is indefinitely prolonged: the promise, which actually comprises the entire show, disdainfully intimates that there is nothing more to come.”

The coyote’s continuous mishaps and deaths accustom young spectators to a society that promises nothing, all the while being founded in the very rhetoric of the social contract.

If there is one political thesis to ascribe to the cartoon on the condition of the “American Dream, “ it might be one that, while expediently offering the hope that existing social arrangements will aid one in realizing his needs, imparts upon him the grim possibility that this will never happen for him (nor the multitudes of others). These arrangements may provide us with the latest gadget, each one more powerful and efficient than the last, but will they furnish us with something more than, as Tocqueville calls, these “vulgar pleasures”? Maybe a future reboot of the series will see to Wile E. Coyote’s victory once and for all.

Author Bio:

Nicholas F. Palmer is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.