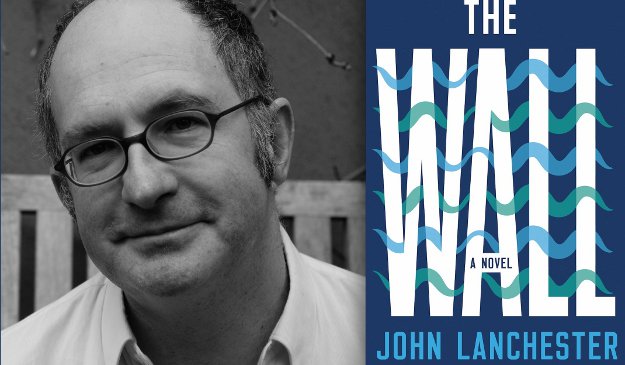

The Future Is Here in John Lanchester's Dystopian 'The Wall'

The Wall

By John Lanchester

W.W. Norton

288 pages

If President Donald Trump wasn’t Donald Trump—that is, if he was someone with tact, perspective, and some degree of literacy—he might borrow a quote from Robert Frost’s poem, “Mending Wall” to make his case for a border wall: “Good fences [or barriers, metal fences, steel slats, etc.] make good neighbors.” Instead, he calls upon our worst fears, invoking the specter of rampaging hordes and a plague of lawlessness, thus making fear rather than unity the raison d'être of his presidency.

Some of the same dynamic is at work in John Lanchester’s new novel, The Wall. A decade or two into the future, after a tumultuous global climate event called the Change, an island nation (much like England) has built a Wall to protect itself against marauding outsiders, known as the Others. Those charged with protecting the borders, known as the Defenders, must maintain a 24/7 vigilance against attack and penetration.

In many ways, it’s a world not all that different from what we know today, except that—as one example—rising waters around the planet have made beaches extinct. Joseph Kavanaugh, the 20-something Defender who narrates The Wall, wonders what beaches once looked and felt like:

“ … and what it was like to have a picnic on the beach, didn’t get sand in the food, and what was surfing like, what was it like to be carried towards the beach on a wave, with people standing on the beach watching you and was it really true the water was sometimes warm, even here, even this far north? … But you know what? The level of my interest corresponds exactly to the number of existing beaches. And there isn’t a single beach left, anywhere in the world.”

Kavanaugh is new to his duties as a Defender, and the dystopia we see through his eyes is conveyed in relatively flat, affectless prose. A good portion of the novel describes the mind-boggling hardships and banality of daily life on the Wall in this prosaic voice:

“You know that you are there for two years. You know that it’s basically the same everywhere, as far as the geography goes, but that everything depends on what the people you will be serving with are like. You know that there’s nothing you can do about that. It is frightening but also in its way a little bit freeing. No choice—everything about the Wall means you have no choice.”

The colorlessness of Kavanaugh’s voice stands in sharp contrast to the world he describes, but it also presents a challenge. The novel takes some time to build momentum, mirroring at times the slow pace of his daily routine defending the Wall from attack. Characters feel thinly drawn, and readers may become impatient to answer the inevitable question, “What happens next?”

An expertly timed surprise betrayal at last sets the narrative in motion. As punishment for allowing Others to get over the Wall, Kavanaugh, his lover Hifa, and another former Defender are put out to sea, where they face life-threatening challenges from the elements and attack by the Others.

In Lanchester’s stripped-down dystopia, the future is perhaps not as imaginatively delineated as possible ("the Change,” “the Defenders,” “the Others”). On the other hand, there’s an alluring simplicity in this approach, a relief from other, more elaborately described post-apocalyptic landscapes:

“God, the Wall must look like a terrible thing from the sea, a flat malevolent line like a scar. So blank, so remorseless, so implacable. We were used to feeling frightened of [the Others], hostile to them; if they came here, we would kill them. It was that simple. But—how must we seem to them! We must seem more like devils than human beings. Spirits, embodied essences, of pure malignity. If we would kill them on sight, what would they do to us, if they could?”

The Wall is a striking departure from Lanchester’s previous work, including Capital, reviewed here in 2012 as “the finest novel yet from a hugely talented writer.” By contrast, the narrative voice of this novel doesn’t achieve the same rich results. Still, The Wall bears the hallmarks of a writer of immense skills, whose strikingly topical story is worth reading as well.

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi is Highbrow Magazine’s chief book critic and author of a recently completed novel, The Confessions of Gabriel Ash.

For Highbrow Magazine