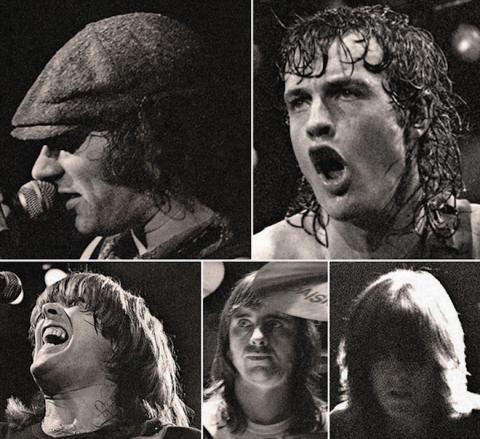

A Long Way to the Top: Rethinking How AC/DC Changed Rock’n’Roll

We’ve got the basic thing the kids want,” AC/DC guitarist Angus Young said in a 1979 interview with Circus magazine. “They want to rock and that’s it.”

And, for the past 40-plus years, that’s exactly what the band has continuously delivered to their enormously large and endlessly devoted base of fans. AC/DC has the notable distinction of being one of the best-selling rock bands of all time, with one of the best-selling albums of all time – 1980’s Back in Black coming in second only to Michael Jackson’s Thriller. Of course, they also have the particular honor of being near-universally panned, ignored, or derided by virtually every self-serious rock critic on the planet.

It’s a well-known conundrum in the rules and regulations of the rock’n’roll canon: If it is popular, it must not be good. While AC/DC has millions of fans the world over and can continue to sell out arena tours (even with a completely different and controversial lead singer), they have very few critical accolades to show for it. They’ve won only one Grammy – for a song released in 2010, no less – and even the likes of Billy Joel managed to beat them into the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame.

What is it that draws fans to and repels critics from their hard rock lair? In a 2014 Forbes piece on the band’s long-lasting success, Ruth Blatt hits the nail mostly right on the head: “AC/DC is a straight-up, no-frills, no bells-and-whistles rock n’ roll band,” she writes, “…never succumbing to the temptation to adopt any musical trends.” That consistency, she says, is what makes for loyal listeners and bored reviewers.

And yet there’s more to AC/DC than straight riffs and shrieking vocals. In fact, anything else that might be considered quintessentially “rock” can be found in their repertoire: fleeting flirtations with the occult, seductive women, plenty of booze, and more than a few songs about rock (or those about to rock) itself. They’re the one-stop shop for all of your rock’n’roll needs.

What sets AC/DC apart from other bands that might also meet these criteria – Led Zeppelin, for example – is that they’re both entirely over-the-top and far too sincere about it all. In an early profile of the band, journalist Phil Sutliffe writes: “They stand for everything I disagree with… and yet they’re so totally honest, open and funny about it, I got carried away with liking them.”

From exploding onstage canons to caps with devil’s horns, AC/DC’s interpretation of the rock’n’roll underbelly boils down to a world that is silly rather than scary, openly transparent rather than enshrouded in mystery, and self-mocking rather than self-aggrandizing. “A belly laugh is often the sanest reaction [to life] and that’s what AC/DC are into,” as Sutliffe explains.

Consider, for instance, Angus Young’s perennial stage attire: the schoolboy uniform. Nothing could have been further from the conventional late-‘70s rock star aesthetic of Dionysian opulence and enshrouded mystique. And yet the school lad getup works: partly because it’s just a memorable gimmick, but also because it highlights and exaggerates all the ways Angus – like so many of his fans – fails to live up to that paragon of guitar god masculinity.

At no more than 5’3” and a mere skeletal casing of skin and bones, Young’s hyperactive and spastic stage antics again show just how peculiar he must have seemed to heavy rock audiences at the time. Despite their almost banal ubiquity now, with songs in blockbuster films, car commercials, and perennial classic rock radio rotation, it’s worth remembering that no one knew quite what to make of this bombastic group of Australians when they first appeared on the UK and American rock scene.

For a good long while they were grouped in with Capital-P Punk, opening for the Dictators and the MC5 on some of their earliest American tour dates and later crashing the CBGB stage to play an unannounced set.

Whether by design or errant rumor, it was widely reported during AC/DC’s first major UK/USA tour that Angus was only 16 years old instead of his actual 21, a misreading that only reinforced the band’s overt lack of sophistication, adolescent brand of humor, and utter determination to simply have a good time, all the time.

AC/DC helped usher a back-to-basics movement during a time when rock was increasingly at risk of over-bloated constipation. In other words, they made rock juvenile again. There is no living teenager who doesn’t think that “Big Balls” is the most cleverly-penned lyrical treatise of the modern age; no child who doesn’t know the chorus to “Highway to Hell” before the age of eight. That’s exactly why, in contrast to other aging rock bands, AC/DC’s demographic range of fans only expands, rather than matures, in age. They’re the perfect “My First Rock Band” because they offer all of the fun gestures of rock’n’roll without any of the need for deeper contemplation.

AC/DC’s music is unassuming, approachable, and, yes, easy to swallow. But that’s what makes it all the more powerful. To reiterate Angus’ point from the Circus interview, kids “want to rock and that’s it.” But he continued on from that line of thought: “They want to be part of the band as a mass. When you hit a guitar chord, a lot of the kids in the audience are hitting it with you. They’re so much into the band, they’re going through all the motions with you.” It’s about basic human connection on a guttural level, in other words.

“If you can get the mass to react as a whole,” Angus concludes, “then that’s the ideal thing. That’s what a lot of bands lack, and why the critics are wrong.”

Author Bio:

Sandra Canosa is Highbrow Magazine’s chief music critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Photo Credits: Harry Potts (Wikimedia.org, Creative Commons); Wikipedia.org (Creative Commons)