The Panama Papers: Why They Matter

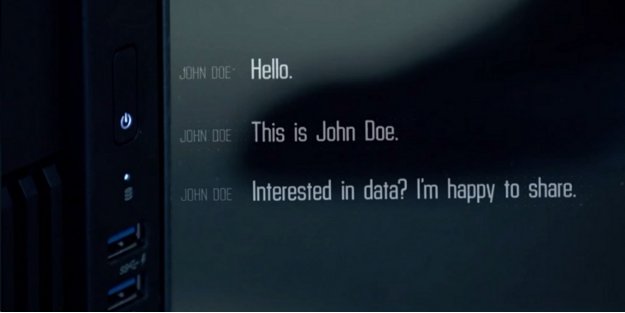

“Hello. This is John Doe,” the message began. “Interested in data? I’m happy to share.”

On Sunday, April 3, the world witnessed the biggest data leak in history. In what has since become known as “The Panama Papers,” over 11 million documents were disclosed detailing how some of the world’s most powerful people have used offshore accounts to conceal their wealth and avoid taxes. Since then, the Panama Papers have had strong repercussions throughout the planet as world leaders, celebrities, and other wealthy individuals grapple with the consequences that have or may arise from this leak.

In the beginning of 2015, an anonymous source contacted German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung about a massive amount of documents detailing the financial dealings of Panamanian law and wealth management firm Mossack Fonseca. The firm, established in 1977 by Ramón Fonseca Mora and Jürgen Mossack, is a global provider of legal and trust services. Though largely obscure before the Panama Papers, Mossfon (as the company calls itself) is the world’s fourth largest provider of offshore services, having acted on behalf of more than 300,000 companies and corporations. The firm employs over 600 staff members and has offices in 42 countries, including in the world’s leading secrecy jurisdictions, such as the Isle of Man, Luxemburg, Cyprus, Jersey, and the British Virgin Islands. The firm specializes in setting up corporations and shell companies in offshore accounts for the purpose of wealth management; and while this practice is generally not illegal, it can be used for criminal purposes like money laundering and tax evasion.

Over the course of a few months, the anonymous source—who aptly named himself John Doe in his initial correspondence with the German newspaper—continued to pass information to Süddeutsche Zeitung surpassing what the newspaper had originally expected. Ultimately, Süddeutsche Zeitung received over 2.6 terabytes of data, making this the biggest leak that journalists have ever had to work with. To put it in perspective, the 11.5 million files the Panama Papers disclosed is a larger amount than 2010’s WikiLeaks, the ICIJ Offshore Secrets and Edward Snowden’s intelligence leaks from 2013, 2014’s Luxemburg tax files, and 2015’s HSBC files combined. Süddeutsche Zeitung shared the acquired files with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), which in turned shared them with a number of its international members, which included investigative teams from the Guardian and the BBC in England, France’s La Monde, and La Nación in Argentina.

Throughout the next 12 months, over 400 journalist from more than 100 media organizations around the world combed over the documents’ contents, which detailed Mossfon’s transactions and financial dealings from the 1970s up until the spring of 2016. To accomplish this, journalists uploaded the documents to high-speed computers which, in turn, turned images into searchable texts using optical character recognition (OCR), much the same way a PDF file is converted into an editable MS Word document. This enabled journalists to search through the massive amount of data, which was made up of almost 5 million emails, over 2 million PDF files, and over 1 million images. Journalists compiled a list of names that included important politicians, celebrities, and well-known criminals and using a search mask similar to Google’s Boolean algorithm, they were then able to search for those names against the database that the OCR had made possible.

In April 3, the ICIJ made a portion of its findings public.

The repercussions were immediate. The documents revealed the murky transactions that are set in motion when opening and handling offshore accounts. The Mossfon data shows that over 200,000 shell companies and corporations are set up in a range of tax haven locations, with Panama, the Bahamas, the Seychelles islands in the Indian Ocean, and Niue and Samoa in Oceania topping the list; the British Virgin Islands held over 100,000 companies alone. Meanwhile, Mossack Fonseca did not always deal directly with the company owners. Instead, they acted on behalf of and upon instructions from intermediaries, which may include lawyers, accountants, banks, and trust funds. This middle management is located all over the world, with the largest concentrations in the Americas being in the United States, Panama, and Uruguay; in Europe in Jersey, Luxemburg, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom; and the United Arab Emirates and China in the Middle East and Asia.

Figuring out where the money is originating from is a far more difficult task to accomplish. This is because the companies’ real owners usually hide behind nominees, who simply lend their signatures and act on behalf on the corporations’ proprietors. The data does show, however, that most of the money flows from countries all over the planet. China and Russia top the list with the most offshore accounts, while Italy, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom are the biggest contributors from Europe. In the Americas, most of the money seems to be flowing from the United States, the British Virgin Islands, and 6 out of the 12 South America countries.

From the outset, journalists set out to find where any given money was coming from, where was it going, and whether or not the structure of the transactions were legal. Through their investigative research, journalists were able to map out links to no less than 12 current or former heads of state as well as at least 60 people directly linked to current or former world leaders; also included in the disclosed files are a number of wealthy athletes and celebrities. Among those named in the data leak are a few African despots who have been charged with looting their own countries, such as Nigeria’s James Ibori, who is now serving a 13-year prison sentence in the United Kingdom after being convicted of fraud totaling nearly $77 million in 2012. Soccer star Lionel Messi, one of the world’s wealthiest athletes, along with celebrities such as Chinese movie star Jackie Chan and United Nations’ Woman Goodwill Ambassador Emma Watson are also named on the Panama Papers as having offshore accounts. These revelations had dire consequences.

Of course, generally speaking, having offshore accounts is not illegal and the practice can be used for a number of legitimate reasons. For example, many countries allow land to be owned only by citizens or locally registered companies, and so a foreigner seeking a vacation home would set up a local shell company to purchase a property. A corporation establishing a joint venture in a country with a weak or corrupt legal system may want to do so through an offshore company based in a place like the British Virgin Islands or the Cayman Islands instead, so the companies can gain access to stronger courts and operate under more sophisticated financial laws.

The secrecy that offshore accounts in tax havens provide, however, can also make it much too easy to stray into criminal activities, such as tax evasion and fraud. And it is exactly this selling point that Mossack Fonseca provides that makes it difficult to clearly gauge the extent of any potentially criminal transactions.

Russian president Vladimir Putin, whose inner circle has been connected with a multibillion-dollar money laundering ring, has denied any accusation of wrongdoing by stating that the Panama Papers were an American-concocted plot to undermine his leadership. At the center of the alleged criminal ring is one of President Putin’s best friends, a cellist by the name of Sergei Roldugin, who has known the president since they were teenagers and is godfather to Putin’s daughter, Maria.

Meanwhile, British Prime Minister David Cameron has received backlash after the Panama Papers revealed that his late father Ian held a number of offshore accounts under the Blairmore Holdings corporation, so named after Blairmore House, where Ian Cameron grew up near Huntley, Aberdeenshire. While no wrongdoing has been proven, Blairmore Holdings’ network ran from the Bahamas to Geneva and it employed a small army of nominees and ghost beneficiaries to sign required documentation that allowed the corporation to avoid paying any UK taxes on its profits since its inception in Panama in 1982. By 1988, the fund was worth an estimated $20 million. A few days after the leak, Prime Minister Cameron admitted to having benefitted from the trust his father had set up, which he claims he sold for a profit of approximately £30,000 before becoming prime minister. Prime Minister Cameron ran for office on a platform for a professed policy to crack down on aggressive tax avoidance.

On one of the most extreme and quickest consequences of the Panama Papers leak, Iceland Prime Minister Sigmundur David Gunnlaugsson was forced to resign his post a mere two days after the documents were leaked. Amid accusations of conflicts of interests, the Panama Papers revealed that the prime minister and his wealthy wife had set up a company in the British Virgin Islands. Prime Minister Gunnlaugsson asked his deputy to take over his post following mounting pressure to resign, even though no wrongdoing had been proven. The calls to action, however, may have touched a more deeply felt emotional nerve with the Icelandic populace, especially after the island country’s 2008 financial crisis that devalued its currency and forced many national banks to shut down. Mr. Gunnlaugsson remains the leader of the country’s Progressive Party (a center-right liberal political party) though his future in politics remains in tumult as Icelanders have continued to take to the streets in protest demanding answers. New nationwide elections are scheduled to take place at the end of this year.

Then, early in May, John Doe released a manifesto of sorts published by the ICIJ. In the 1,800-word statement titled “The Revolution Will Be Digitized,” John Doe affirms that he doesn’t work for any government or intelligence agency and never has, and declares that income inequality is one of the defining issues of our time. After citing the need for more and better whistleblower protection and hinting at more revelations to come, John Doe offers to cooperate with law enforcement agencies and prosecutors seeking to investigate potential wrongdoings. ICIJ and its partner publications had previously stated that they would not provide any documents or evidence to law enforcement, citing journalistic ethics and code of conduct. That same day, on May 6, Mossack Fonseca said that it had issued a cease-and-desist letter to ICIJ urging the organization not to release any of the documents. The firm stated that doing so would break attorney-client privileges, adding that the files were obtained illegally while the Mossfon itself had committed no crime. Nevertheless, that Monday ICIJ published more leaked files online.

More files remain that have not yet been published, and if John Doe’s statement holds true there are still many more to come. A few countries have already launched internal investigations into possible tax evasion and money laundering schemes. Meanwhile, 11.5 million files are a massive amount of information to comb through; and for now it is a matter of waiting to see what more revelations they will bring to light, and the possible consequences that will come about.

Author Bio:

Angelo Franco is Highbrow Magazine’s chief features writer.

For Highbrow Magazine