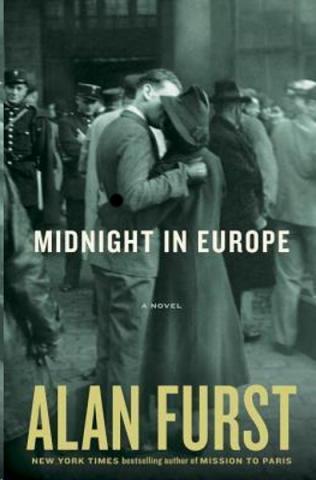

Smuggling Guns and Battling Fascism in Alan Furst’s ‘Midnight in Europe’

Midnight in Europe

by Alan Furst

Random House

272 pages

No one can accuse Alan Furst of veering away from a successful formula. In Midnight in Europe, he once again sets his spy drama in the perilous realms of various European countries just before the Second World War. As any faithful reader will tell you, Furst has carved out a unique niche in espionage fiction, with an emphasis on deeply researched details of those times. But by now, in his 14th novel, a sort of underlying familiarity has set in, which the talented author does little to up-end in the course of the story.

It’s December 1937. We meet Cristian Ferrar, a Spanish émigré and corporate lawyer doing some Christmas shopping while visiting New York City on business: “At Saks Fifth Avenue the window displays were lush and glittering—tinsel, toy trains, sugary frost dusted on the glass—and a crowd had gathered at the main entrance, drawn by a group of carolers dressed for a Dickens Christmas in long mufflers, top hats and bonnets.”

Almost immediately, Furst drops the reader into a specific time and place (the “sugary frost” in the Saks Fifth Avenue window display) and manipulates cliché (“a Dickens Christmas”) while somehow staying above it. It’s a measure of his skill that the image seems so effortlessly drawn and depicted.

Soon thereafter, back at his home base in Paris, Ferrar is recruited by elements of Spain’s Republican government to help purchase and smuggle arms to fighters on the battlefields of Madrid and elsewhere. Ferrar’s exploits take him from Parisian nightclubs to dance halls in Berlin and a railyard in Poland.

The main character’s professions may change from one novel to the next, but Furst’s heroes share certain indelible traits. Whether it’s Frederic Stahl, a Hollywood actor in Mission to Paris, Colonel Jean-François Mercier in The Spies of Warsaw; Dutch naval captain E.M. DeHaan in Blood of Victor; or journalist Carlo Weisz in The Foreign Correspondent, these men (and they are always men) are loners caught up in the turmoil of their times. They’re sophisticated and world-wise (not to say cynical), highly observant and circumspect in their professional lives, fluent in various languages and proficient in the ways of sex and love—and, above all else, unwilling participants in events leading to global war.

By and large, the novels succeed because Furst is just so damn good at uncovering key details about the period. In Midnight in Europe alone, the reader learns about ambulances “with blue paper concealing their headlights from Franco’s spotter planes” and how prostitutes in Madrid must let their hair grow out black “because the city’s supply of peroxide was needed as antiseptic for the wounded.”

At the same time, there seems to be a great deal of explaining that goes on in Midnight in Europe. While it’s safe to assume that faithful fans know a great deal about circumstances leading up to World War II, there will always be some who don’t—and it appears that, for these readers, Furst feels obliged to have his characters spell out the facts in occasionally awkward ways.

At one point Ferrar meets with a colleague in Paris who outlines a forthcoming mission to purchase arms in the Polish city of Danzig, “or what used to be Danzig,” his colleague notes. “It’s now The Free City of Danzig, set up the by Versailles treaty to give the Poles a port on the Baltic, and administered by the League of Nations.”

What’s more, the colleague goes on, “Who really runs Danzig is the city administration, which is Polish. Now Poland, like every country in Europe, is a battlefield in the political war between the left and right. And it so happens that, among leftist Poles in Danzig we have friends. The Republic has friends.”

A lot of exposition is packed into this clump of dialogue, spoken in words few living, breathing human beings are likely to express. This occurs with some frequency throughout the novel, and the unfortunate thing is that it’s not really necessary. A writer as skilled and knowledgeable as Furst can surely produce dialogue that educates the reader in a more lifelike manner.

In the end, Ferrar and the other characters in Midnight in Europe don’t feel as “lived-in” as in Furst’s previous works. They’re more often described rather than put into action, and aren’t as freshly drawn as the protagonists of his most suspenseful novels, like The Polish Officer and Blood of Victory. When it comes to plunging the reader into the murky and romantic milieu of pre-war Europe, Furst remains unmatched. But it may be time to veer away from what’s proven so successful in the past.

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi is Highbrow Magazine’s chief book critic.