Gauging the Real Effects of Media

Opinion

What if we knew that the fictional rapes in HBO’s mega-hit “Game of Thrones” caused real rapes in the real world? What if we knew that the portrayals of gay characters in “Modern Family” caused actual states to legalize same-sex marriage?

The catch, of course, is causation. Medical research can prove that cigarettes cause cancer, but the best social scientists can do is to say whether there’s a “correlation,” or not, between media and behavior. And sometimes even that isn’t clear. When you comb communication research for evidence for or against a correlation between violent video games and violent behavior, for example, you can find enough on both sides to muddy any conclusion.

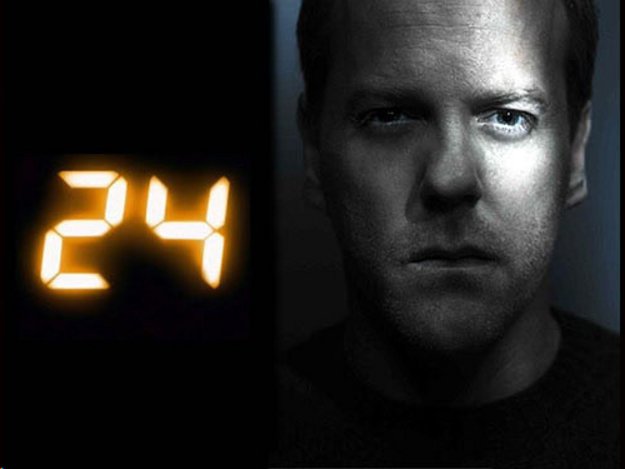

Yet this doesn’t correspond with our experience. More reporters than I can count have said they became journalists because of “All the President’s Men.” Efrem Zimbalist Jr., who died last Friday, played Inspector Erskine for nine seasons of “The FBI,” and his Los Angeles Times obituary noted that he was awarded the FBI’s highest civilian honor for being “an icon who inspired a generation of FBI agents.” As Jane Mayer reported in The New Yorker, the dean of West Point, along with three of the most experienced military and FBI interrogators in the country, flew to Hollywood to tell the creative team behind “24,” which begins its 12th season this week, that his students, despite being told by their teachers and textbooks that torture is wrong and doesn’t work, were learning the opposite lesson from Kiefer Sutherland’s character, Jack Bauer.

There wouldn’t be an advertising industry if people weren’t susceptible to messages. POM Wonderful wouldn’t rent billboards promising (falsely) to prevent prostate cancer, the fossil fuel industry wouldn’t spend millions on spots claiming (falsely) to produce clean energy, candidates wouldn’t fork over billions of dollars to local TV stations for (pants-on-fire) political ads if all their money could buy were some wispy correlation.

Anecdotes aren’t data, and there’s always the risk that a confirmation bias – a stacking of the evidentiary deck – is at work in citing examples like these. But it would be odd to ignore what Uncle Tom’s Cabin did to abolish slavery, what “On the Beach” did to increase awareness of the threat of nuclear war, what Fox News narratives are doing to undermine the scientific consensus on climate change.

Today, because so much content is consumed digitally and shared socially, and because there is so much data to be mined about our knowledge, attitudes and behavior, there now exists an unprecedented opportunity to quantify the impact of media. It won’t be a true science of cause and effect until neurobiology makes some big leaps forward, but the methods and tools for measuring the differences that media make are dramatically evolving, with consequences that are both encouraging and discomfiting.

What if it were possible to fine-tune the content, marketing and distribution of a documentary or news story to maximize its impact on a target audience? What if a soap opera or a telenovela, a Bollywood feature or a Nigerian video, a Chinese social media site or an American advertising campaign, were able to finely calibrate their effects on what people knew, believed and did after they encountered them?

The answer depends on what moral and political values you hold. I think that family planning, vaccination, voting, access to health care, human rights, renewable energy and sustainable agriculture are public goods, and that promoting them makes the world a better place. If media can improve the odds that the societal needle moves in those directions, I’m all for it. But other people may think that ethnic cleansing, consumerism, state censorship, fracking, machismo, oligarchy and theocracy are good things; they would call the content I favor propaganda, and I would return the favor. One person’s pro-social media is another person’s psyops and agitprop. If you increase the power of media to move audiences, you do it for white hats and black hats alike.

That worries me. I’m also concerned about the potential consequences for freedom of expression, especially artistic expression. What would happen if data demonstrated beyond a reasonable doubt that parts of our popular culture were toxic – that the connections between song lyrics and misogyny, video games and violence, rape on TV and rape on campuses and in the military, were as strong as the connections between air pollution and asthma, coal ash and birth defects, fluorocarbon gases and skin cancer?

We have laws banning child pornography and marketing cigarettes to kids. How would we regulate entertainment found to be harmful without turning good intentions into a witch-hunt, without pulling art from museum walls and literature from library shelves? How would we draw a line between news that covers violence and hatred, and news that incites violence and hatred? I do want a world where my kind of do-gooders have more tools to increase the good they do, but not at the cost of empowering algorithms that score media against someone else’s idea of a moral yardstick.

I come down on the upside of this dilemma. I’ve cast my lot with efforts to use media to repair the world and to improve how we measure their effectiveness. That’s been a big part of my work for a number of years (have a look at what the Norman Lear Center’s Hollywood, Health & Society program, and our Media Impact Project, are up to), and I’m grateful to the foundations and agencies and donors who support it. But when it comes to the mystery of how words and images affect what people know, what they feel and how they behave, there’s always something to be said for a little pre-emptive paranoia.

This article was first published in Jewish Journal.

Author Bio:

Marty Kaplan is the Norman Lear Professor of Entertainment, Media and Society and directs the Norman Lear Center at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. In the Carter Administration he served as chief speechwriter to Vice President Walter F. Mondale.