Fordism and the Fast-Food Industry

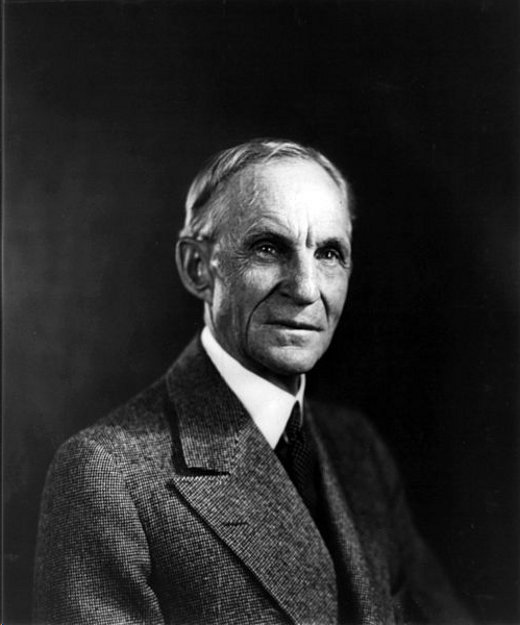

In the winter of 1914, yet another portion of American history dosed with a “routine” trough of economic recession, the New York Times reported that Henry Ford had doubled the base wage of his factory employees to a flat $5.00 a day. Naturally, as any other sharp businessperson of his ilk would have done, Ford shrouded his motivations for raising these said wages behind a pseudo-egalitarian veil.

Pursuant to this veil, he would go on to proclaim a few years later that “one's own employees ought to be one's own best customers.” The main idea being that it would seem appropriate to be able to drive to work in the very Model T that you yourself had built on the factory floor. Profit sharing, we get it. It sounds nice. But Ford was only trying to mitigate his employee turnover rates in providing wages higher than his competitors found in GM and Chrysler.

Laughably, soon after this increase in wage, Ford was even asked if he was a socialist.

We need not spend our time deconstructing the neoliberal fictions that buttressed and protracted what would become known as Fordism throughout the 20th century, that cruel notion of future profits being voluntarily distributed by successful corporations amongst their lower-level employees. The idea that when the economy is booming, everyone’s well-being is elevated.

Also, as a means of quickly dispelling such a thought, we need look no further than the unprecedented disparity between the profit margins of America’s most successful fast food chains and the wages of the workers that make it all happen, from the sun-burned potato farmer to the midnight cashier enveloped in cruel, florescent light behind a drive-thru window.

However, a simple inversion of Ford’s notion of an employee being the best customer of the company for which they work might best articulate what is at stake in this nation’s burgeoning fast-food workers’ movement.

What if the alliterative and eponymous slogan of Chicago-based “Fight for 15”, the 15 referencing the strikers’ desired hourly wage, is an existential one, a fight for their right to usurp the corporate forces that threaten their emotional, physical, and economic health?

What if a wage of $15.00 an hour enabled the fast-food worker and his or her family to eat elsewhere?

Does the antidote to Fordism’s central thesis lay simply in its syntactical inversion? Could this indeed rupture the often cruel aesthetic of the American dream?

Lauren Berlant, in her profoundly focused 2011 text Cruel Optimism, outlined what she called the slow death of the American worker who must fight for life with the means of the cruelly ironic living-wage.

Utilizing David Harvey’s polemical assertion that “under capitalism sickness is defined as the inability to work” as a point of departure, Berlant excoriates the Regimes of Accumulation as she tries to articulate the structures of feeling, the effect, if you will, that have allowed poverty wages and ill health to remain obscured for so long, as they have grown perversely and increasingly commodified and racially compartmentalized under the guise of culture.

Declaring that the use of the word culture is no accident, as it relates to racial identity, poverty wages, and obesity, she goes on in stating that “as food practices seem more cultural, obesity can seem less related to the conditions of labor, schooling, and zoning that construct the endemic environment of the ‘epidemics’ emergence.”

Berlant sees no reason to segment causality in the case for health and the mitigation of poverty in the United States. It would be myopic in not contending that poverty and poor health are two sides of the same coin minted by the cruel optimism of Fordism.

As far back as March of 2012, progressive policy analysts began crunching numbers that would grant low-wage workers the quantifiable might needed to bolster their bold, placard-wielding aesthetic. John Schmitt, a senior economist with the Center for Economic and Policy Research in Washington, D.C., authored an analysis of the national minimum wage as it relates to the productivity growth of the U.S. economy since 1968. With the most crucial neoliberal benchmark in tow, Schmitt offered this potent critique:

Between the end of World War II and 1968, the minimum wage tracked average productivity growth fairly closely. Since 1968, however, productivity growth has far outpaced the minimum wage. If the minimum wage had continued to move with average productivity after 1968, it would have reached $21.72 per hour in 2012 – a rate well above the average production worker wage.

In just two sentences, Schmitt is able to re-historicize the injustices that have well plagued the American worker since the rise of Reaganomics and the amoral, upward redistribution of national wealth that has since served as the precedent for a normative behavior rooted in profit maximization. His study’s name more than most likely says it best as it is titled The Minimum Wage is Too Damn Low.

As Banksy’s mobile Ronald McDonald statue will attest, which has of late been positioned next to various McDonald’s franchises in New York City in unofficial confederation with Fast Food Forward replete with a shoe polish covered performer shining Ronald’s extra-oversized red shoes, it has been too damn long since a significant raising of the nation’s minimum wage.

The structures of feeling that have for so long facilitated such degrees of social injustice appear to be eroding with an exponential acceleration.

The very week Banksy’s work found itself on the streets of the South Bronx, the UC Berkley Labor Center, in conjunction with the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, released a report titled Fast Food, Poverty Wages: The Public Cost of Low-Wage Jobsin the Fast Food Industry.. And CREDOaction, the Web-based social change organization that has led the fight in taking this report viral, summarized this astounding piece of scholarship best as they reconfigured it into a direct accusation addressed to the corporate powers that be:

A whopping 52 percent of fast-food employees’ families are forced to rely on public assistance to put food on the table or see a doctor because you pay them poverty wages. That means Americans are picking up the check with nearly $7 billion in tax dollars a year – while the fast-food industry reaps billions in profits. It’s outrageous and it has to stop. It’s time to pay your workers $15 an hour so they can make ends meet and Americans can stop paying the hidden costs of poverty wages.

Additionally, if we are to account for the billions of dollars worth of farm subsidies appropriated yearly to corporate corn and soy bean producers that, in turn, artificially shrink the cost of fast-food’s raw materials, how might this enlighten the perceived paths to change?

According to the Environmental Working Group’s Farm Subsidy Database, the US Congress allocated nearly 4.5 billion dollars in 2012 alone amongst only 16 producers of corn (used to expeditiously fatten the nation’s cattle supply) and soybeans (major source of deep frying oil and extreme preservation practices).

With the disclosure of these tax dollars’ appropriation as means to lowering the cost of the production of unhealthy foods (did not find a single green vegetable on the EWG’s subsidy list, unless we count tobacco), and the price of those same foods being utilized to set a “living” wage, then the failure of that wage to keep a full-time worker above the poverty line that subsequently requires additional supplementary funds to marginally offset this labyrinthine injustice, what else must be made clear?

Imagine if these 4.5 billion dollars were to be equally distributed amongst the 3.6 million American workers, per the U.S Bureau of Labor Statistics, that earned wages at or below the federal minimum in 2012.

The quantificated aesthetics of this struggle are widening the political stage, seemingly reminiscent of the not to be forgotten battle cry of “99 percent” that was appropriated in the wake of the Great Recession. But do we not remain in its wake? Have the President’s words of late even entertained an agreed-upon notion of progress in his stating on December 3rd that “it’s well past the time to raise a minimum wage that, in real terms right now, is below where it was when Harry Truman was in office."

If we were to parlay John Schmitt’s diction, we could say that the minimum wage has been too damn low for too damn long. And Harry Truman left office in January of 1953, lest we forget. That’s nearly 61 years ago.

The most vocal counterpoint to this struggle, the National Restaurant Association (yes, another N.R.A.) has made itself ironically clear in response. This lobbying association, with “more than 750 staffers working to empower all restaurant owners and operators to achieve more than they thought possible,” per its Website restaurants.org, has routinely relegated the strikes against it as publicity stunts.

However, this NRA is precisely correct in uttering their misguided pejorative. Has protest ever been anything other than a publicity stunt? Protest, the act of and responses to it, is precisely its own point, right?

With nearly a year of increasingly fervent protests upon its resume, and backed nationally by the Service Employees International Union, the Fast-Food Workers’ Movement has made contagious their expansive, political stage. Just this past October, thousands of Wal-Mart employees staged the first multi-city walkout in the company’s 50-year history. How can the American people continue to disregard events such as these as isolated fits of frustration?

As mentioned previously, the strikers have the President’s ears. Banksy is on board. They need not worry about offending Henry Ford by making his philosophies become their own opposites. Whose ears and voices next?

Upon completing the previous sentence and commencing with this one, I checked my inbox and found an email from McDonald’s employee Nancy Salgado who is currently aiding CREDO Mobilize in their efforts to further stoke this wave. Nancy tells me that strikers and supporters were reported present on the streets in more than 250 cities across the country on December 5th, 2013.

I’m reminded of political philosopher Alex De Tocqueville declaring that democracy was an irreversible phenomenon.

It appears that this strike is not to be undone.

Author Bio:

William Eley is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine and is presently a Master’s candidate of Aesthetics and Politics at the California Institute of the Arts.