Auster-Coetzee Letters Shed Light on Literary Friendship

Here and Now: Letters 2008-2011

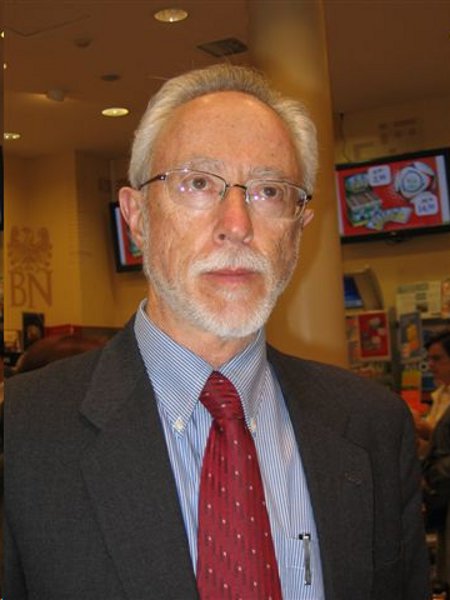

Paul Auster and J.M. Coetzee

Viking

248 pages

Here and Now is a collection of letters between the Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee and the American novelist Paul Auster. The correspondence began in 2008 when Coetzee, author of the Booker-prizewinning masterpiece, Disgrace, sent a letter to Auster, author of The New York Trilogy, suggesting that an exchange of letters “might be fun, and we might even, God willing, strike sparks off each other.”

Over the next three years, letters and faxes went back and forth between Auster in Brooklyn and Coetzee in Adelaide, Australia. The correspondence touched on a wide-ranging array of subjects, from friendship and sports to Israel, the global financial crisis and the creation of literature.

In its form and structure, Here and Now seems almost defiantly anachronistic. Who sends letters anymore? In the past, the passage of time between letters sent and received was a necessary element in the act of correspondence; today, such delays are irrelevant and distracting. It’s to their credit that, communicating across a vast swath of time and space, Auster and Coetzee are able to maintain an intelligent, ongoing dialogue, while ignoring the convenience of email and other far faster modes of communication.

The letters have a curiously contradictory tone. Auster and Coetzee share an obviously warm friendship, which in itself is the subject of many of the early letters. They are gifted writers and veteran world travelers, and each has a wealth of knowledge and experience to draw upon.

On the other hand, the letters soon acquire a patina of Olympian timelessness—as if they were written as much for eventual publication as for the desire to share intimate thoughts and feelings. The writers exchange no sharp words and the emotional temperature of the letters remains steady throughout. No one’s asking for the strident discord of cable TV talk shows; still it may prove difficult for readers to stick with an antiquated literary form that doesn’t waver much in pitch and tone. The longed-for “sparks” envisioned in the first few letters never really come to pass.

Nevertheless, fans of these authors will enjoy the asides and impressions occasioned by the letters. In 2010, for example, after bemoaning yet another questionable “improvement” of the modern world, Coetzee asks a supposedly rhetorical question:

“How does one escape the entirely risible fate of turning into Gramps, the old codger who, when he embarks on one of his ‘Back in my time’ discourses, makes the children roll their eyes in silent despair? The world is going to hell in a handbasket, said my father, and his father before him, and so on back to Adam. If the world has really been going to hell all these years, shouldn’t it have arrived by now? … But what is the alternative to griping? Clamping one’s lips shut and bearing the affronts?”

To which Auster replies:

“The truth is, griping can be fun, and as rapidly aging gentlemen, seasoned observers of the human comedy, wise gray heads who have seen it all and are surprised by nothing, I feel it is our duty to gripe and scold, to attack the hypocrisies, injustices, and stupidities of the world we live in. Let the young roll their eyes when we speak. We must carry on with utmost vigilance, scorned prophets crying into the wilderness—for just because we are fighting a losing battle, that doesn’t mean we should abandon the fight.”

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi is Highbrow Magazine’s chief book critic and the author of a novel, The Moon in Deep Winter.

Photos: David Shankbone (Wikipedia Commons); Merius Kubik (Wikipedia Commons).