Fiction: De Gaulle and I

This short story is an excerpt from a novel in progress by Tara Taghizadeh.

December 1970

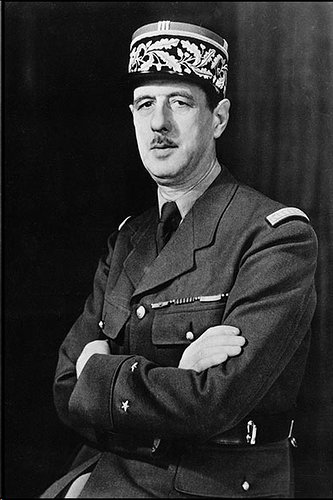

In the picture I have of my grandfather, he is standing next to General de Gaulle. You can’t see his face, though. What you see is the General in the midst of a crowd, and beside him is a man wearing a bowler hat with his back to the camera. The owner of that hat was my grandfather – according to him, anyway.

“General de Gaulle is dead. France is a widow,” he’d say, shaking his head this way and that. Actually, President Pompidou said it on the radio, on a day as cold as hell when crows gathered on skinny branches covered in snow. The old man, six-feet-plus, casket measuring three metres, was dropped in the ground, not a word, not a sigh, as France gathered with empty eyes and a hoarse voice muttering nothings under its breath.

Nights, shut up in that hole of a room, walls plastered with cutouts of De Gaulle in different poses, my grandfather would write letters of condolence to Madame Yvonne de Gaulle – nee Vendroux – the girl he used to fancy. Five-foot madame in shabby checkered coat and bun glued to the top of her head, felt up by grandfather in the back of a bus in Calais. Biscuit-manufacturer’s daughter, convent school Yvonne, once an easy lay, or so he said. Pasty-faced, dull-eyed madame, but could she dance. He said he’d put his hands on the small of her back and she’d come to life – looked almost pretty she did. Who would’ve thought? The General’s wife.

De Gaulle standing, De Gaulle sitting, walking, talking, young De Gaulle, old De Gaulle, all those pictures in his room. Right in the corner, where the light didn’t hit, was one of Madame with bun and aprons, eyes half shut.

“Il etait France,” grandfather would scream, repeating the General’s own words: “I am France.”

“I cry for France,” grandfather would shout and leave, climbing one stair after another to bang a door, silence following, as always. We were never sure why grandfather cried for France, but he did, especially when arguing with our Yugoslavian butler, Ladislav, or the time Nicolas got a tattoo.

He was my mother’s father, a De Manesse. She called him “Pere,” not even “Papa.” She told us it would be polite to call grandfather “Monsieur de Manesse” or “Colonel” but father said Monsieur would do. Grandfather was touchy about things like that. Mother said he was a proud man, but father said grandfather wasn’t proud, he was an ass.

He would walk the streets, trying not to stagger, refusing to use that silly cane. He said he could see, well enough, I suppose. He’d squint his eyes and look around. “Nothing left to see,” he’d say, “all gone,” he’d say, turning his head left to right, right to left, wondering if she’d show.

“Ma chere Yvonne,” he’d write under the light, when the house was dark and no one saw. Old Madame left alone with a cold stiff of a man, a great man, a tall man, a man who stole grandfather’s girl.

I saw him dance in his room, soft music from nowhere, probably that Johann Strauss fellow he liked so much. He spun round and round, moving his hips, singing, talking to God knows who. He’d done this before, long ago, in a boozy old ballroom in Calais, whisky on his breath, whisky on her breath, when evening faded into pitch black.

Grandfather hated everything practically. Le Monde and cough drops and men who wore red ties. Father asked, How can you hate a cough drop? But Grandfather said you could. He said if you give anything too much thought, you will hate it. He wasn’t too fond of father, either. Mother said Grandfather never forgave her for marrying a career diplomat. “Useless, pretentious know-it-alls,” Grandfather would say, especially when father’s friends were over.

“Ma chere petite…let me mourn with you….France has lost a hero.” He’d written every day since the General’s death. He’s include a carbon copy of that photo of him and De Gaulle, drawing a circle around the bowler hat. Afternoons at 3:00, he’d ask me and Nicolas to check the mail. His brother sometimes wrote. “Was there anything else?” he’d always ask.

No response from his old girl. Had Madame forgotten the young soldier who’d shown her a good time all those years ago? Pretty girls forget their suitors, not the likes of Madame though. Not too many beaus hanging around plain old Yvonne back then. Above it all now, was she? Married the General and forgot all those whisky-hazed days of old Calais.

Hunching over a stack of daily letters, he’d rummage through them, looking for God knows what. His illegible scrawl had decorated the envelopes which held his heartfelt sympathy for Madame. One, two, three, four….no reply to any of them.

One afternoon, he pulled Nicolas and me aside and ordered us to type his letters. Maybe the post office couldn’t read his ungodly penmanship, or so he thought. That’s why Madame wasn’t responding, he’d say. It was a conspiracy, he’d explain. Nicolas said that perhaps Ladislav, being a former Communist and all, had infiltrated the postal system in an effort to sabotage Grandfather’s efforts, but Grandfather pinched Nicolas’ ear really hard and told him to start typing.

What happened next was Nicolas’ fault; it was his idea, anyway. He said it would be funny if we wrote a letter to Grandfather from Mme. de Gaulle. We wanted Ladislav to write it, but Nicolas said Ladislav would back out and think he’d get deported or something if he got caught. So Nicolas sat down and wrote it himself. All it said was:

“Monsieur de Manesse, Thank you for your persistent sympathy and those lovely pictures of your hat. I would like to return the favor.”

Then Nicolas cut out this picture of a woman wearing a huge straw hat with tropical fruit dangling from it from Mother’s Vogue magazine and put it in the envelope. I didn’t want to be a part of it. I knew Grandfather would get mad and try to shoot us with his BB gun like that time we found all his nudey magazines and showed them to Mother.

Exactly at 3:00, Grandfather hollered for us to check the mail. We ran back to the house and handed him the envelope. He adjusted his glasses, frowning at the unfamiliar handwriting. He opened the envelope neatly. Nicolas and I stood by the staircase, giggling, waiting for him to start screaming. He looked just like Mother standing there – the gaunt face and the same awkwardly stiff posture. He must have read that thing twenty times. He kept looking at the picture and reading the letter. I didn’t feel like laughing anymore. It wasn’t funny. I don’t know what it was. Maybe he looked too much like mother then, so thin and serious. There was nothing ever funny about mother. Or maybe the way he kept squinting at the picture of the woman in the fruity hat. My throat felt dry. Grandfather didn’t even look at us. He just folded the letter, went upstairs and started yelling at mother.

“Your son and daughter are not worthy of France,” he screamed. “You have raised disrespectful hooligans.,” he yelled before marching off to his room and banging the door shut.

He didn’t show up for dinner. Mother didn’t say much. She never did when she was upset. I never saw her and grandfather talk much really. But once I saw her stand behind his chair and stroke his head.

I had to pass by his room to get to mine. He saw me walk by. “Come here, I want to talk to you.” I closed the door and he pointed for me to sit. He sat across from me and lit a Gitane. The whole has always stank from the smell of his cigarettes. He was wearing a maroon bathrobe. He’d bought it in Burma, or somewhere. That’s what he said, anyway. Every time we asked, where did you get this or that? he’d name some faraway place. Mother said he was telling the truth though.

It was dark in there. I couldn’t see well. I shifted on the bed, hoping he’d say something. He coughed. I looked up. He kept coughing. Finally, he spoke.

“Do you want one?” he asked, offering me a Gitane. I didn’t answer.

“Don’t think I don’t know you smoke,” he said. “I’ve seen you and your brother.” I shook my head. He dropped the Gitane on my lap.

“If you want to smoke, smoke a real cigarette. Here, taste it, go on.” I picked it up and licked the tobacco.

“That’s what real tobacco tastes like,” he said.

He walked over to his desk and rummaged through it. He picked up something and came and stood in front of me.

“Can you do this?” he asked, laughing. It was a photograph of one of those nudes.

“Are you embarrassed? Do you look down your nose at her?” I didn’t answer.

“Don’t,” he said. “You’re no better. You think you are, don’t you?” he asked softly, as if he were just curious. I nodded.

“Well, you’re not,” he said. “One of these days, you’ll also have to compromise yourself, like that girl. Maybe not in the same way, but you’ll do what you have to do just to get by.” He lit another Gitane. “You’ll have to take orders from some idiot who is clearly less superior, but you’ll kiss their ass anyway, to make a living. Or you’ll fall in love with some man who you’ll convince yourself loves you, and you’ll start hating yourself when he leaves.” He stopped to crush out the cigarette. “There’s always someone who’ll trip you up.” He stopped to look at the photo again. “You’ll feel as good as she does then.”

He turned his back to me, something outside the window having caught his eye. He turned to face me again.

“You know, when we lived in Provence, there was a man who used to work for me; Daumain was his name. A meek, quiet man who never said a word. I made him miserable for three years. I swore, I yelled, I screamed. He never said a word. All he said was, ‘Good morning, Sir’ and ‘Good evening, Sir.’ I stopped eventually. I grew to respect him. So one day, I went up and invited him to have dinner with me and your grandfather, and he turned around and spat on my shoe. Just like that, he spat. Then he put on his hat and left for good.” He stopped to watch my expression. “And all I could think of, was how it took that sad, stupid bastard three whole years just to spit.”

He searched through the items on the side-table, then came to sit next to me on the bed. He was holding that photo of him and De Gaulle. He handed it to me.

“Maybe you should keep this,” he said. “Then you can tell people that this man standing next to the General is your grandfather.”

I placed the picture on my dressing table. Grandfather stayed cooped up in that dark hole of a room, listening to sorry old Strauss records, with those pictures of De Gaulle and his Missus wall-papering his every thought. We could hear him coughing for days on end. He hadn’t touched his food. Best to leave him alone for a while, mother said. But on an unusually sunny day when spring winds had started whispering through the trees, I ran breathlessly all the way from the garden up to grandfather’s room to hand him the letter Madame de Gaulle had written.

Author Bio:

Tara Taghizadeh is the Founding Editor and Publisher of Highbrow Magazine.

©Copyright Tara Taghizadeh

Photos: Archives de la Ville Montreal (Flickr); Thomas Thomas (Flickr); Lauren Manning (Flickr).