Anamorphic Illusion and the Magic of Current Events

In a provocative short film from 1991, Anamorphosis, identical twin film animators Stephen and Timothy Quay explore a powerful device at the heart of histories of Western visual illusionism. Anamorphosis, from the Greek “formed again,” refers to a mode of perspective by which hidden or trick images emerge from an otherwise composed visual scene.

Remember that running gag from Kevin Smith’s Mallrats when William cannot see the sailboat in the Magic Eye poster? From Leonardo’s Eye (1485), which can only be construed from an oblique angle, to Hans Holbein’s painting, The Ambassadors (1533), that transforms a distorted image at the bottom of the frame into a human skull from the right vantage point, perspective illusionism hinges on the disjuncture between the human eye and its embodied position. Sometimes a device is required as a substitute for the movement of the spectator’s body. In an 1850 painting of Napoleon III, a funhouse reflection of the French Emperor is set right only placing a conical mirror at the center of the image.

Revealing secret symbols or transforming a flat plane into a 3-dimensional world, anamorphosis activates a sudden shift or rupture in its impression on the spectator. Whereas perspective seeks to systematize an image of the known world for the benefit of the human eye, anamorphosis “leads the eye slowly through incomprehension and then offers a resolution.” The Quays’ documentary about anamorphosis, which enlists film puppetry, stop-motion animation, and other hybrid techniques to depict the history of aesthetic trickery and distortion in Western art, would seem to be a perfect metaphor for the broader economy of the news media industry today.

Rachel Maddow put it succinctly in reference to a slate of recent news scandals including Obama’s Department of Justice wiretapping the Associated Press, the IRS targeting conservative groups, and more political backlash from the September 2012 attacks in Benghazi: “It is going to be a long, hot, stupid summer.” The temporality of present-day news media, which serialize an ever-unfolding slate of loosely linked threads through the incessant urgency of the NEWS UPDATE, seems to systematize tricks in perception as our new mode of comprehension. Whereas anamorphosis hinges on delay before a hidden dimension is revealed, our current events economy flattens the experience of this anticipation. We are constantly reframing and clarifying gluts of information before we have even had the opportunity to register their distortion.

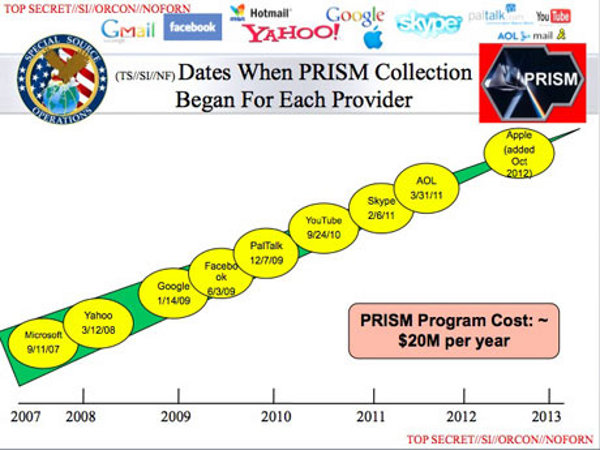

The recent government surveillance scandal—that the National Security Agency actively collects phone log records of millions of Americans under a secret FISA order—is especially illustrative. Like Fox News’ recent, “earth-shattering” supplement to the Benghazi saga, knowledge of this FISA order is not necessarily “new” news. We know that the government possesses these powers to spy on us “for our own protection” under the Patriot Act. What is new, however, is the story’s context and framing: the program PRISM that gives the government the executive authority to monitor our Internet and phone activity. When Google, Apple, Facebook, and YouTube enter the scene—our online networks that provide the backdrops for everyday glimpses of our global world—the reframing of old news strikes us like an experience of anamorphosis: the upturning of a known entity that we had taken for granted.

Just to be clear, I am not suggesting that PRISM is anything other than profoundly disturbing and severely unethical. Rather, I am attempting to draw attention to the world of everyday images that embed our comprehension of political scandal: to the constellation of clickable icons and photo-spliced backdrops whose habitual distortion and revelation somehow impact the positions that we take in relation to ongoing developments in geopolitics.

The analogy between visual anamorphosis and the attempt to provide a framework for processing our diet of mediatized news information is of course imperfect. In anamorphic illusion, the visible presence of a distorted image in the frame draws attention to the imminent experience of upturning and revelation—for example, the elongated shape that gets transformed into a skull in Holbein’s Ambassadors painting. In contrast, in our media information economy, the whole background is distorted. The only object in focus is the one momentarily under scrutiny: the anamorphic figure reframed before we have even had the attention span to register its existence.

Anamorphic projection formats provide another analogy for understanding how our gaze adapts to the slew of new apparatuses for mediating our perspectives on the world. With anamorphic lenses, films shot in widescreen on 35mm stock get compressed and seamlessly reframed for digital projection to standard aspect ratio screens. All of this can happen during the process of projection itself; by placing a different lens on a film machine, a picture shot in 1.37:1 can be reconfigured for a standard 4:3 aspect ratio.

Given the immense range of different screen sizes and formats that we navigate among everyday—from iPhones to Jumbotrons—the anamorphic widescreen metaphor could be especially instructive for parsing the compressed temporality of our everyday knowledge positions. To return to the funny Mallrats example, it would be as if William, instead of missing the sailboat entirely, had missed the point of its absence -- if he had believed that the hidden message itself were the only way to view the picture.

To invoke a more current film comparison, in one of the few summer Blockbusters this year not to depict the full-scale apocalypse, Now You See Me, a group of traveling magicians known as “The Four Horsemen” (only symbolically “of the apocalypse”) feed on political discontent to dramatize the spectacle of illusion. They pretend to rob a bank that they had in fact already robbed by claiming to use a teleportation machine linking Las Vegas to Paris—and then shower the audience with 3 million euros that rain down from the ceiling. More pointedly, they hold a show in New Orleans and publicly transfer money from the bank account of a wealthy insurance industry magnate (Michael Kaine) to the depleted accounts of the Katrina victims whom he had cheated out of their entitlements.

The film takes for granted that the magicians’ tricks will be exposed; their how-tos and hidden mirrors do not generate much suspense or anticipation. As the political stakes of the Four Horsemen’s increasingly complex trick apparatus intensify, the film’s real sleight-of-hand revolves around holding its own pieces together. What does the vindication of Katrina victims have to do with the global, trick-laden cat-and-mouse game that is unfolding? In a rapid procession of reframings and de-framings, the greatest surprise is that our astonishment never gives way to information fatigue. But what holds us in place? For now, maybe we should look to FISA for answers—after all, the government might very well see what we know better than we do. Let’s just hope against hope that Now You See Me does not envision a sequel: Now You Don’t?

Author Bio:

Maggie Hennefeld is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine. She currently lives in Providence, R.I., studying in a Modern Culture and Media Ph.D. Program at Brown University.