How Popular Media is Helping to End the Stigma of Mental Illness

Whether your understanding of mental illness is limited to what you’ve seen on the silver screen, or as intimate as a firsthand struggle, the topic has occupied a continual space in our national discussion, eliciting controversy and fascination. Today, there are nearly 60 million Americans who suffer from a mental illness, and it continues to present a quality of life, household and community issue. While there is reason to believe the national dialogue is evolving, there is still a pervasive discomfort and ignorance that keeps millions of those who suffer from getting treatment, trapped in their own purgatory. Barring mere misinformation, we have a huge network of social and institutional problems when it comes to mental illness, from stubborn stigmas to reckless and unchecked drug companies to a lack of comprehensive resources, necessitating a robust political and social undertaking to address this crisis that directly affects nearly one in four Americans.

The deep-seated prejudices that brand mental illness a sign of weakness, a character shortcoming or feigned for attention have poisoned how many perceive the issue. To wish the pain of mental illness on or off at will is a futile exercise, since any person who has suffered knows the pain of a mental illness controls and consumes. Living becomes a toilsome test in survival, and even treatment is in and of itself a trying process. Notwithstanding the gravity of the affliction itself, for those ashamed of their illness, the added burden of actively hiding their illness weighs noxiously on one’s soul and psyche. A severe want in education has kept sufferers in the shadows, either in denial, or too afraid to come out for fear of social, political or economic repercussions. Although an abnormal psychology is a condition like chronic pain or allergies that likely will never be entirely cured, it can be managed and treated.

The experience of mental illness is not universal; there are as many diagnoses (people often suffer form more than one mental illness, known as comorbidity), symptoms, treatment plans, and coping mechanisms as there are sufferers. Although a vigorous discussion in the psychiatric community is ongoing, treatment implementation for these disorders is still not comprehensive enough to account for the particular needs of each patient, making it hasty, imprudent and often irrevocably damaging. The need for holistic, tailored solutions cannot be overstated; yet mental health policy has fallen prey to corruption by drug companies, creating a paradoxical vacuum of chronic over- and under-treatment. Drug companies and health insurers have a vested interest in encouraging overinflation of diagnoses, putting people on major prescription drugs needlessly when they could have been treated or helped otherwise. On the contrary, while millions of people are prescribed anti-depressants, only one third of people with severe depression receive any treatment for it. Combine this lack of clinical proficiency with cultural stigmas, misunderstandings, and preconceptions, and there is no wonder why needs of patients are largely unmet.

Recent statistics show a disturbing upward trend of suicide rates in the United States. From 1999 to 2010, the suicide rate among Americans ages 35 to 64 rose by nearly 30 percent. Even more alarming are the skyrocketing suicide rates among military veterans. According to the Department of Veteran affairs, a US military veteran commits suicide nearly once every hour. These numbers have a variety of compounding factors, however suicide is a tragedy intimately correlated to mental illness, particularly for veterans who often suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD symptoms include constant sensory re-living of deeply traumatic events, and many veterans are shamefully denied or forced to wait months for comprehensive mental health care when they return from service.

We have not yet arrived at a point, nor may we ever, where we’re readily willing to take on as a collective distressing, dark, morbid, and unglamorous human stakes. Mental illness by nature starkly manifests itself in the form of the aforementioned traits, all of which evoke elements of mortality to which we have a natural aversion. There has been no major cultural initiative to try and re-evaluate the discomfort that accompanies our traditional shared consciousness toward mental illness. Mental illness is not a difference of phenotype or sexual preference, so when we frame it in terms of a fight for equality and acceptance we must deal with the fundamental themes of darkness and uncertainty that make it a taboo subject, and that’s where storytelling becomes useful.

Popular culture has proved to be an indispensible backdrop for the evolution of society. Although academics and political figures contributed tirelessly to the effort, gay rights, for example, could not have arrived where it has as efficiently as it did without Bravo, ‘Glee,’ the ‘No H8’ campaign, and iconic celebrities working to spread awareness. A similar paradigm is needed to reform views on mental illness. With a slew of macabre films like ‘Girl, Interrupted,’ Donnie Darko and One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest coming to define the mental illness experience, it is no wonder we have cultivated a psyche of chagrin toward the subject. To say these films are merely exaggerations would be an injustice to the scope and severity of mental illness, but the oft-misunderstood truth is that most sufferers of these disorders are capable of day-to-day functionality just like their healthier counterparts. We need to hear their stories too.

In order to change the perception that mental illness is a character flaw, that a person with a mental illness is violent or dangerous, or is a person incapable of a meaningful existence, we are going to have to begin a national dialogue that unpacks and normalizes mental illness, just as we have for a variety of other equality struggles.

Movies and television shows have typically fed into and reinforced stereotypes and myths about mental illness, but a recent wave of thoughtful portrayals in popular media demonstrate a welcome shift in the industry. The first major saving grace may be Homeland, Showtime’s mega-hit, critically acclaimed original television series about CIA agent Carrie Mathison, played by Claire Danes, and her riveting work as a counterterrorism expert. Carrie, the show’s flawed protagonist, is brilliant, attractive and successful, and also suffers from Bipolar Disorder. Homeland is not a show about mental illness, but the disorder is a requisite part of the story, implicit within the five-minute mark of the series premiere when Carrie fishes out and swallows a lone green pill from a bottle of aspirin before heading to work at CIA headquarters. We also find out in the first episode that Carrie’s superiors and mentors at the CIA are not aware of the illness, after a colleague comes across Carrie’s pills and confronts her.

Bipolar Disorder, once formally known as manic-depressive disorder, is a psychiatric diagnosis affecting more than 5 million Americans, characterized by alternating episodes of mania and depression that last for hours, days, weeks or months depending on the individual. Manic episodes are typically marked by characteristics like impulsiveness, extreme confidence, high levels of productivity, and an inflated sense of self. Depressive episodes follow with traditional characteristics of depression including lack of interest, deep sadness, listlessness and excessive sleep. We witness Carrie endure both types of episodes on Homeland.

[Spoiler] Rather than run the risks that come with the CIA learning her secret, Carrie avoids formal treatment and gets pills underhandedly from her reluctant psychiatrist sister. Near the end of the first season Carrie is finally outed to the agency amidst a manic episode, let go from her job, hospitalized, and treated with electroshock therapy. Some critics lament Carrie’s furtive treatment as clinically dishonest, however, that Carrie has expended such effort to conceal her illness is a critical story to tell. It serves to enlighten millions of viewers of the potentially catastrophic sacrifices people with mental illness often find themselves forced to make.

Carrie is tempestuous and often defies authority, begetting trouble and leading to her eventual Season One downfall, but her instincts are almost always dead-on. Carrie’s keen ability to empathize, think outside the box, and delve into the psyche of those she is investigating, combined with ample natural intelligence are what make her such an effective and skilled intelligence officer. Whether Carrie’s strokes of genius can be accredited entirely to what intuits from her own psychopathology we are uncertain, but an emotional acumen informs her work just as much as her intellect. Carrie’s ability to relate to people and subsequently allow her own emotions to act in honest accord help unlock the compelling national security-centered plot so crucial to the series’ success.

Aside from the realism of the interplay between her career and medical condition, Danes’ accurate and authentic portrayal of the illness itself (she spent hours watching footage of individuals with BPD who recorded themselves during episodes to research the role) relays the essential truth that most of its sufferers aren’t violent or evil. Episodes of depression, mania, and psychosis do not always happen in the confines of a straitjacket, in fact, they rarely do. As intricate details of the storyline unfold before Carrie’s dogged and importunate eyes while in the throes of mania, the ingenuity of Homeland’s portrayal of BPD crystallizes. The show’s aim in tying manic symptoms to Carrie’s work is not to glorify or romanticize the illness, because Carrie’s emotional struggles are real and readily apparent, rather it is to show that people with BPD have wide-ranging life experiences and are not defined exclusively by their illness.

In an interview with Elle Magazine, Danes says of the role, “I’m always concerned that her mental condition not be a gimmick; I’d like to see how she [Carrie] maintains stability. It’s not sexy or fun. But that’s true about people with this condition: They’ll have plateaus when things are fine.”

Homeland’s writers combined with Danes’ shrewd acting have spawned something incredibly profound in Carrie, where the audience both understands the unique gravity of her illness and career without losing their ability to relate to or have affection for her. Carrie is talented and influential but is not a savant or a hermit, and she craves the kinds of personal and professional successes, relationships, and joys the rest of us do. Her work is objectively of gargantuan importance, but she makes very human errors nonetheless, like falling foolishly and irresponsibly in love with a person of professional interest, an experience of the human condition millions of people without BPD can relate to. She is wholly mortal despite her extraordinary circumstances, and that’s why she is such an important role model, particularly for people suffering from mental illness, even more particularly for women with mental illness, who have been historically subjected to unthinkable abuse and humiliation.

Although regarding a more insidious subject, Carrie’s own prophetic words get to the crux of the issue at hand, “You’re trying to find out what makes them human, not what makes them terrorists,” she says to a coworker in Season One. The viewer does not forget about Carrie’s illness while watching Homeland, but also knows that Carrie is not just her illness; she is an amalgamation of her genetics, her spirit, her conviction, her interests, her relationships, and her dreams, just like the rest of us. We can never be entirely sure whether Carrie’s psychopathology plays a role in her important premonitions, but we do know that her disease is painful and real, and that she has realized tremendous success in spite of it.

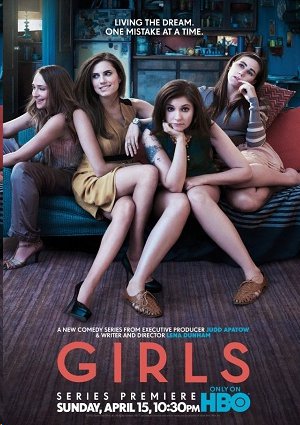

Homeland, whose third season premieres fall 2013, has been lavished with praise and accolades from the entertainment industry, but the show also received a Voice Award, which recognizes TV and film professionals in their efforts to educate the public about behavioral health problems. Homeland is not the only recent show dealing with mental illness to garner critical and commercial success. HBO’s hit series Girls has recently delved into the subject as its protagonist’s Obsessive Compulsive Disorder was exposed in the last season.

Portrayals of mental illness in popular media are not novel, but critics and advocates are hopeful that the quality of these portrayals will come to benefit real-life sufferers by informing viewers of the realistic and diverse experiences of the mentally ill, rather than playing on tired and gratuitous stereotypes that only harm and stagnate forward progress.

Films like Silver Linings Playbook, which was nominated for Best Picture as well as several acting categories at the 2013 Academy Awards and for which Jennifer Lawrence won the Best Actress category, have also come to normalize the mental illness experience. Silver Linings Playbook is a movie about mental illness but it is also a movie about love, loyalty and loss. The film is different from Homeland in that multiple characters are suffering from mental illness, and that the plot is simple and relatable. What is similar is the normalcy with which mentally ill characters are portrayed.

Silver Linings Playbook may write certain aspects of mental illness in an over-simplified or unrealistic way, however what makes it so valuable to the discussion of mental illness is its use a relatively simple romantic-comedy template to show that its mentally ill characters are neither superhuman nor monsters. With complex yet likable characters that diverge from the prototypes found in a typical romantic comedy film, Silver Linings Playbook ultimately does its audience a service. Mental illness is part of the story, but a love for sports, family and tradition are also what made the movie so well received, as it appeals to the pathos of both academics as well as an American audience perhaps unfamiliar with mental illness.

By tying mental illness to the stereotypical angst-ridden mismatched couple destined to be together at the end of a formulaic romantic comedy trope, Silver Linings Playbook elicits the type of universal compassion needed to understand the mental illness experience. “What if we know something you all don’t,” a bipolar-stricken Bradley Cooper believably quips to a room filled with family and friends toward the end of the movie, the ‘we’ including himself and other mentally ill characters. The fact that Cooper’s statement is even up for discussion, and not immediately scoffed at or disregarded, neither by the other characters nor the viewer watching the film, is indicative of progress.

Unfortunately much of the national dialogue surrounding mental illness has come on the heels of escalating gun violence in the United States, wherein several of the perpetrators of recent gun massacres had reportedly exhibited warning signs of mental illness and were fatefully overlooked. We must be careful not to inextricably link violent tendencies to mental illness. We mustn’t shut down conversations or efforts to create legislation that deals with mental illness; the problem is not to load the term “mental illness” with images of lone wolves who walk into movie theaters and elementary schools and shoot people down without remorse. The vast majority of people with mental illness are not violent and will never become violent. We cannot accept calls to perpetuate a culture of fear surrounding the mentally ill, to quarantine them, or put them in a national database. What we desperately need is comprehensive education, and a cultural movement towards compassion and understanding.

Carrie Mathison is just one of millions who can teach us that those with mental illness are capable of goodness, of human pleasure and error, and of abundant success. The more we know of stories like Carrie’s, the likelier it is that we value common humanity over prejudgments and fears. Once we reach this point as a society, anything short of full inclusivity and acceptance becomes unacceptable. We know millions of Americans are suffering in the dark and we also know that the suffering is treatable. The mental health community now must work in concert with advocates and professionals to shape the cultural and political landscape that will lead to acceptance, recovery and healing.

Author Bio:

Gabrielle Acierno is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.