The Central Park Five’s Korey Wise Discusses the Wrongful Conviction

From New America Media:

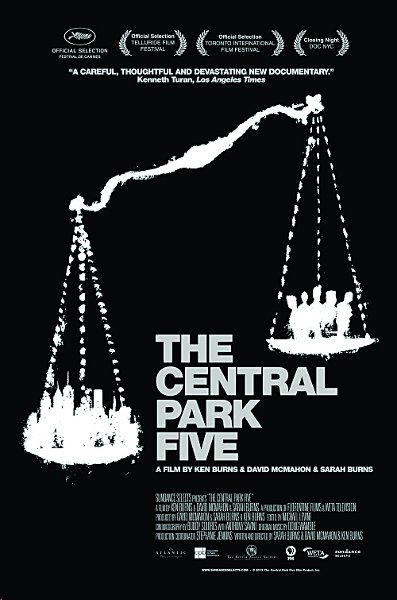

Editor’s Note: “The Central Park Five” a new film by Ken Burns, tells the true story of the five black and Latino teenagers from Harlem who were wrongly convicted of raping a white woman in New York City's Central Park in 1989. Korey Wise, who at age 16 was the only member of the group to be tried as an adult, later met the real rapist on Rikers Island. Matias Reyes finally confessed to the crime and his DNA testing led to the Five's exoneration in 2002.

Korey Wise sits smirking through a one-man play, saying “hmph!” and “ummm” now and then. Youth groups, activists, and college students have packed the auditorium at the National Black Theatre in Harlem, where Wise will join a panel after the play on wrongful imprisonment -- a subject he knows all too well.

In 1989, Wise and four other young black and Latino teenagers were convicted of raping and beating a white investment banker in Central Park, leaving her for dead. The media called her the Central Park Jogger and the accused the Central Park Five. No evidence linked them to the crime except for their confessions, which came after relentless hours of police interrogation. They recanted shortly afterwards, but those statements were still enough to send them all to jail. Wise was 16 but sentenced as an adult to five to 15 years.

Last year, a decade after an inmate named Matias Reyes confessed to the crime, resulting in all five of the boys’ exoneration, Sarah Burns, Ken Burns, and David McMahon released a documentary about their story, “The Central Park Five.” Wise, who went free after 13 years, is now suing the city for wrongful imprisonment.

During the panel, a young man in the audience talks about being imprisoned at Rikers Island at 16. Wise can relate. He sits straightforward, hands clasped, no emotion on his face, almost dazed.

“Wow,” is Wise’s unspoken reaction.

Later, in his Bronx apartment, he compared Rikers Island to another local landmark.

“The Bronx Zoo is dealing with all types of elements,” he said.

Yet he sees Rikers Island as a place where rebirth happens, because inmates’ natural instinct and appetite for survival kick in. “There’s no mommy, no daddy,” he said. “Just you.”

Wise’s instincts did kick in one day on Riker’s Island after an altercation with a fellow inmate, Matias Reyes. “Destiny made it his business to come see me,” Wise tells the audience, explaining how the true rapist of the Central Park Jogger confronted him over control of a television.

Thirteen years later, almost five hours away at Auburn Correctional Facility, Wise and Reyes met again on the yard where about 10,000 inmates congregated. Reyes approached Wise and established that he too had transferred from Rikers Island. When inmates travel from prison to prison, it’s hard to meet new people, so they tend to stick with familiar faces. Reyes broke the ice by apologizing for the fight; Wise accepted.

“I see you’re still maintaining your innocence,” Reyes said.

“I guess so, yeah,” Wise said.

“Are you religious?”

“Nah, I’m not religious. Why, what’s up?”

“Well, you know, I just became religious.”

“Well, all praises be to the most high for you then.”

The next day in the chapel, Wise got a call from his mom. Inmates summoned to the chapel usually expect to hear about a death in the family, but not Wise.

“I don’t know who you talked to, but whoever you talked to, he freed you,” his mother said.

Living with scars

The white walls and concrete floors in Wise’s Bronx apartment living room are as bare as a prison cell’s. The wind from the open window competes with an accordion heater right beneath the sill. He stands up from the wood framed chair, takes off his green long-sleeved shirt, and points to the scar on his wrist.

“I’m not a five.”

He lifts his undershirt to show a cut on his abdomen.

“I’m not a five.”

He pulls his pants down halfway exposing a permanent purple bruise on his upper thigh.

“I’m not a five,” Wise said, referring to the Central Park 5.

Wise insists that he’s an individual – more than a part of the group. Out of the five convicted, he was the only one tried and sentenced as an adult because he was 16.

“He spent twice as much time in prison and was in an adult maximum-security facility,” said his lawyer, Jane Byrialsen, with whom he has developed a familial relationship.

“The damage that he sustained from that experience is incomparable,” said Byrialsen, who added that Wise can be a loner sometimes.

Documentarian Sarah Burns echoed Byrialsen’s sentiments. “The juvenile facilities were no walk in the park but they were not the same thing as where Korey served all of that time,” she said.

Wise has been struggling with maintaining his individuality since this nightmare began years ago. Burns said the media contributed.

“I think part of the problem with that initial coverage in 1989 was that it lumped it all together like they were this ‘wolf pack,’ as the newspaper said,” Burns said.

By the time Reyes confessed to the crime in 2002, Wise was 30 and the other four young men had returned home; they only served seven years. “If I had [gone] to Spofford [Juvenile Center] with them it would be none of this. Reyes would still be playing stickball,” he said, meaning Reyes never would have confessed had they not run into each other.

Wise still sees his social worker almost once a week but he doesn’t feel the need for a therapist, Byrialsen said. Wise doesn’t work now; he receives a disability check for being partially deaf in his right ear and having post-traumatic stress. He also gets Supplemental Security Income, a program that pays disabled adults who have limited income and resources.

Wise spends most of his time hanging around his old neighborhood and speaking on behalf of the Innocence Project at events.

He hardly goes anywhere without his iPod and headphones. Sometimes when Wise is riding on the train he’ll see a poster for the documentary. “I just feel a pain, it hits me,” he said. “That’s why I try to keep my hip-hop in my ears.”

Over the years his lawyer noticed that music helped Wise escape his pain. “He still listens to ‘80s music from when he went in,” said Byrialsen. “It’s like he’s still stuck. It’s like he’s still sort of that 16-year-old kid in a way.”

She hopes that he will soon be able to move on with his life and not be continuously reminded of the past, but her hopes and reality seem farther away than she and Wise would both like.

Looking for justice

Wise is suing the city for $50 million in damages for being wrongfully convicted, a case he filed 10 years ago; it could be a year before he sees any closure. Being unemployed has given him time to sit in the courtroom for about 40 depositions. His lawyers and the defense will have to go through 50 more before this summer. During these depositions Wise witnesses the city’s law department present evidence against his case as if they doubt Reyes’s confession should have exonerated him. Watching all of these legal arguments doesn’t do much for Wise’s healing, Byrialsen said.

“I think that it’s very hurtful. I think he suffers every day,” she said.

The city’s law department responded to this reporter’s request for an interview with an emailed statement from Celeste Koeleveld, executive assistant corporate counsel for public safety, that said in part:

"As we've said before, the City stands by the decisions made by the detectives and prosecutors. The confessions, hearings, and trials all presented ‘abundant probable cause’ for the plaintiff’s conviction… Nothing unearthed since the trials, including Matias Reyes’s connection to the attack on the jogger -- changes that fact.

Under the circumstances, the City is proceeding with a vigorous defense of the detectives and prosecutors," Koeleveld wrote.

Byrialsen said the longer this case remains unsettled, the more Wise’s closure is delayed.

“The thought that you’ve been exonerated, and you’ve been out all these years and people still think you did it, I don’t think you can ever escape that,” she said.

But Wise said sharing his story is very therapeutic. Almost weekly, he appears through The Innocence Project in panel discussions, rallies, and screenings of the documentary.

In 2002, after being released, Wise changed his first name from Kharey to Korey.

Byrialsen said he no longer wants to be associated with all the negative documents that carry his old name.

Wise thinks highly of Burns for creating the documentary and giving him the opportunity to share his story. “The doc is beautiful. It hurts to the core,” he said.

Just as he left his old name behind, he speaks about his past self as if he is two different people.

“I love to see little Korey do his thing, ‘cause he done died,” he said, meaning prison almost killed his youthful spirit, “and came alive, like, 13 times in 13 years. Little Korey was just looking to have his life. Not have his life torn away from him,” Wise said.

“So when I look at him -- as his new representative, his lawyer -- I have to give the audience his life, because he’s no longer here to tell it.”

Author Bio:

Mea Ashley is a contributing writer for the Washington Informer.