How Electronic Publishing Democratized Authorship and Paved the Way for New Reading Habits

This is Part 2 in a three-part series about new trends in the publishing world.

In the previous installment of this article, I introduced an overview of changes in the publishing industry by comparing the changes in publishing with the changes in the music industry a decade ago.

Particularly, I examined how new reading habits and e-books, small presses, Amazon.com, self- publishing, and the democratization of authorship affects traditional publishing–the soon-to-be Big 5. These changes are a boon for literature and for readers and they provide opportunities for publishers, players on both sides of the spectrum argue.

Mik Strøyberg, Director of Consumer Engagement for Issuu–a company on the leading edge of digital design for e-books–says “We’re actually on the verge of a publishing renaissance.” Strøyberg, like many, sees the traditional publishing model as outdated, so it may come as a surprise that Michael Pietsch, the soon-to-be CEO of Hachette Book Group agrees with much of Strøyberg’s position. Pietsch believes "we're in a golden age for books — reading, writing and publishing.”

Of course, the incoming head of a major international publishing house needs to say this, but Pietsch, like Strøyberg, sees opportunity. He believes that many changes in technology “work to connect readers with writers now are the kinds of things that publishers have dreamt of doing since Gutenberg first put down a line of type."

For Pietsch and others in the industry, the traditional publisher still has a role, and it’s not just releasing content. Strøyberg argues that “everyone can be a content provider” and that the role of a publisher like Issuu is that it provides the digital means by which that content can be accessed in an attractive format.

Issuu’s “books” are attractive, and the interface by which we read and engage the page feels close to the experience of reading a “real” book. Furthermore, after a quick perusal of the “poetry” titles available, one gets a quick glimpse of the democratization of publishing in action. The site includes individual volumes of poetry in a variety of styles and quality; furthermore, one can get the collected poetry of a fifth grade class. Across the country, budget cuts have killed school newspapers, yearbooks and literary journals: services such as Issuu provide the means to publish these books inexpensively, and–better yet–distribute them beyond the school or school district. Such opportunities are exciting for students, teachers, parents and student writers.

Distribution is the main subject of any discussion about the future of publishing. Whether we are talking about e-books, bookstores, self publishing or the role of libraries, what we’re really talking about is distribution.

For instance, one of the biggest issues that face self-published authors is running the business of being a self-published author. You have to promote the book. It’s for this reason, Pietsch says, that publishers remain necessary. “[Authors] want someone who can help them take what they've created and get it everywhere. And the business of publishing has become much more complex. You're not just selling books to local bookstores. You're selling them to independent bookstores; you're selling them to bookstore chains like Books-A-Million and Barnes and Noble; you're selling to Costco, to Target, to Wal-Mart, to Urban Outfitters, to this huge, complicated physical book network, and at the same time on all the digital retail platforms that are out there.”

For Pietsch, and many others, the book is not going the way of the record. Shoppers could rarely listen to records before they bought them in a record store, but they can thumb through a book. Still today book purchases are often impulse buys; therefore, people still buy traditional books.

Some evidence seems to support this position. A recent Publishers Weekly article notes that Diamond Book Distributors reported double digit gains in 2012. Simon & Schuster reported a bump in sales in 2012. Jeffrey Lependorf, Executive Director of Small Press Distributors says, “The changes facing publishing are indeed affecting the distribution of independently published literary books. Most of these changes, for now though, may not be visible to most readers. For example, while SPD does currently offer a number of e-book titles, most of our readers still prefer to read what we offer in print.”

And from McSweeney’s: “Sales of e-books still represent a small percentage of the overall book market. Depending on who’s counting, the portion of the market is between 8 percent and 10 percent. When Amazon reports that their e-book sales are now larger than their paperback sales, it’s easy to extrapolate this to encompass overall reading trends. But that would be a mistake. Amazon is an Internet company, and it follows that their sales would favor electronic delivery of text. They are but one of many ways people get books, and the ratio of printed books to e-books changes drastically with each venue.”

That’s not to say that the e-book market isn’t heating up, but it suggests that people have a different relationship to their books than to their records: Think about it. We used to make cassette copies of our records (and mixed tapes) to take our favorite music with us. People keep libraries, with the hopes of coming back to favorite books or sharing them. You can’t share a digital download (though you now can sell back your e-book).

This issue of sharing e-books is the crux of one of the other distribution conundrums facing publishers, and it has to do with the role of libraries. It’s been a complicated relationship. Paper books get worn out, fall apart, don’t get returned, get damaged and, in the case of best sellers, libraries often need multiple copies of traditional books. With mot libraries having e-book kiosks, publishers needed to find common sense ways to regulate e-book lending and prevent pirating. Libraries became the unwitting no-man’s land between Big Publishing on one side and Amazon.com/Apple iTunes/Google on the other. Some publishers such as Penguin and Simon & Schuster stopped selling e-books to libraries, whereas others, such as Random House which quintupled the library fees of e-books, chose to find ways to make money from e-book sales to libraries. The problem is further complicated by the variety of e-readers patrons may have, each with its own proprietary e-book formats.

John Taube of the Allegany County (Maryland) library system believes that the future of libraries is in some ways to work with nontraditional publishers: small presses, self-publishing authors, and other content providers who value the library’s role as a content aggregator for the public. He believes that “the distribution of books [e-books] via the Internet will become the norm” further limiting the role of libraries in the community.

Of course, people go to libraries for more than books, and libraries, like bookstores, provide an opportunity for the impulse lend. Libraries, like bookstores, also traditionally provide a forum for getting the word out about certain books (display, recommended or staff picks, etc). Social networks, however, from Facebook and Twitter, to Goodreads and even Amazon.com reviews, allow for book recommendations to transcend the community library. Use of such resources has also become a means by which self-published authors and small presses promote their titles in order to increase distribution.

A whole cottage industry of “positive reviewers”–services designed to just hype a book on various sites– has sprung up. A recent CraigsList ad offered 100 positive reviews for $200: enough to generate a buzz about a title. Such buzz is often the only way to get a small press or self published title out of the new slush pile–not the work waiting to be read by an editor for acceptance or rejection, but to get it out of the glut of titles self-published every year. As long as books are bought and sold, someone is going to need to market a title.

One way to avoid this, as YouTube does with video content, will be to make everything free. Or else have a subscription service ala NetFlix for books. Both, argues Issuu’s Strøyberg, are possible futures for publishing. Issuu exists in both paradigms as much of what it currently offers is public or promotional content that is free or teasers: partial books designed to entice a reader to buy the whole thing.

Authors meanwhile are left to wonder if there’s a role for genius in all this anymore. What, if anything, does the democratization of publishing, threaten. Strøyberg notes the risk of a “new narcissism” in which an author’s writing is limited by one’s need for “the approval of those around us. We want to be re-tweeted, want to be ‘liked.’ That’s what’s happening with reading. The risk of social networks is that the commentary of others on our works will dictate the work we produce.”

It’s similar to the argument from the ‘90s against creative writing workshops, which suggested that MFA students wrote work to appease their classmates and teachers, thus limiting their ambition and genius. The response was always something akin to “genius rises to the surface.”

Traditional publishers have been a boon and bane to genius traditionally. It’s no doubt the same will be true about the democratic vistas of digital publishing. Right now, the book industry, although in flux, allows for genius, mainstream and blue-collar writers alike to find the publishing paradigm that works best for them: paper or electronic; self publishing, or trade publishing; small press or big six.

And authors, of whatever ilk, may be the winners. Says Pietsch: “Anything good that happens, any genuine excitement that a book elicits can be amplified and repeated and streamed and forwarded and linked in a way that excitement spreads more quickly and universally than ever before. And what I'm seeing is that really wonderful books — the books that people get genuinely excited about because they change their lives, they give them new ideas — those books can travel faster, go further, sell more copies sooner than ever before. It's just energized the whole business in a thrilling way.”

Author Bio:

Gerry LaFemina, a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine, is the author of a book of stories (Wish List), two books of prose poems, and six books of poems, including Vanishing Horizon (2011, Anhinga Press). He directs the Frostburg Center for Creative Writing at Frostburg State University. He divides his time between Maryland and New York.

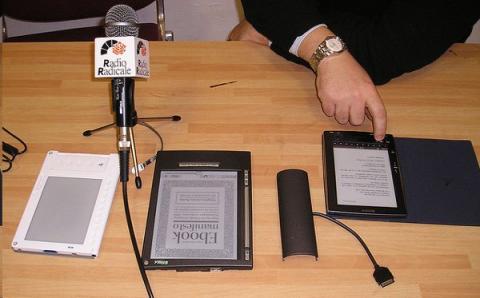

Photos: Luca Conti, GoXun Reviews (Flickr, Creative Commons).