The Influence of Woody Guthrie Continues, a Hundred Years Later

Woody Guthrie wrote songs about an America with a stunning landscape, of majestic forests, rolling rivers, and deep valleys, hugged by two oceans, where inequality and social injustice sowed roots. He wrote folk songs for the everyman, songs of tragedy and of triumph, ballads of spiritual death and rebirth.

As Guthrie stated, “A folk song is what’s wrong and how to fix it, or it could be who’s hungry and where their mouth is, or who’s out of work and where the job is, or who’s broke and where the money is, or who’s carrying a gun and where the peace is.” In short, Guthrie and his fellow folksinging friends – including Leadbelly, Sonny Terry, and Cisco Houston – sang and wrote songs about struggle and redemption -- a message that has been carried on long after Guthrie’s death by artists like Pete Seeger, Bruce Springsteen, Bob Dylan, Ramblin’ Jack Elliot, Billy Bragg, Joan Baez, Tom Morello, and countless others.

Income and wealth gaps between rich and poor peaked in the 1920s, the stock market had crashed, people at the top of the social hierarchy lost their fortunes, those at the bottom lost their livelihoods, and unrest spread across the country, all just prior to some of Guthrie’s most prolific songwriting. It was, in many ways, a broken world that Guthrie came up in -- a world that had already witnessed the carnage of one world war, with a second one looming, and one of the nation’s most troubling economic disasters.

People in America, the land of the free, the land of democracy and opportunity, were hungry and hopeless. Severe drought and dust storms threatened the economic viability of many parts of the country, particularly the states of Oklahoma (where Guthrie hailed), Texas (where Guthrie rambled), New Mexico, Kansas, and Colorado.

The postwar Jazz Age glories and evils elegantly described by writers like Fitzgerald were part of a bygone yesterday, a brief era of fabulous wealth, booming consumerism, and excruciating poverty. Ushering in a more unwelcome era of uncertainty and depression, writers like John Steinbeck emerged in the subtle limelight, describing this period in touching prose through the remarkable story of the Joad Family.

For those who have not read Woody Guthrie’s autobiography, Bound for Glory, Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath provides a good portal into this world from which Guthrie emerged as a cultural figure. It was a world of social injustice, income and racial inequality, of workers struggling for basic rights, of families leaving their homes for better opportunities, hoping beyond hope without any grasp on the reality of the harsh conditions they would face in their search for a better life in the Golden State.

Guthrie and Steinbeck were, in many ways, inextricably linked together, not just in the similarities between the real-life Woody Guthrie and the fictional Joads, but in the appropriation of Steinbeckian characters and themes by Guthrie.

Guthrie wrote many memorable songs based on Steinbeck’s classic. These works – namely “The Ballad of Tom Joad,” “Vigilante Man,” “The Ballad of Pretty Boy Floyd,” and “Do, Re, Mi,” – appeared on his 1940 album Dust Bowl Ballads. They were songs that, like many of Guthrie’s works, described social injustices and highlighted cultural contradictions with humor and wit.

In “Pretty Boy Floyd,” a ballad about a real-life bank robber who is also immortalized in Grapes of Wrath, Guthrie sings, “Yes, as through this world I’ve wandered/I’ve seen lots of funny men/Some will rob you with a six gun/And some with a fountain pen.” It is not a stretch by any means to think of figures today in the aftermath of several corporate scandals that would fit these lyrics.

“Do, Re, Mi” describes the problems faced by those dispossessed of their livelihoods in the American prairielands, condensing the deep Steinbeckian prose into four neat and simple verses. The Dust Bowl and the Depression were social problems, and many were seeking the same escape, following promises westward to California, the land of golden opportunities. But Guthrie tells his audience: “California is a garden of Eden, a paradise to live in or see/But believe it or not, you won’t find it so hot/If you ain’t got the do, re, mi.”

While Guthrie’s America may have been a land of inequality and injustice, it was also a land of struggle and hope. Hope was the key to many of Guthrie’s songs. It gave reason to continue in this struggle of life, against the hardships that battered the soul and crippled the will to fight. As Guthrie writes in his book Pastures of Plenty: “The note of hope is the only note that can help us from falling to the bottom of the heap of evolution, because, largely, about all a human being is, anyway, is just a hoping machine.” As Steinbeck said of Guthrie (words that could have equally applied later to the young Guthrie-influenced Bob Dylan): “Harsh voiced and nasal . . . there is nothing sweet about Woody, and there is nothing sweet about the songs he sings. But there is something more important for those who will listen. There is the will of the people to endure and fight against oppression. I think we call this the American spirit.” In his songwriting, Guthrie, perhaps more than any other folksinger, captured the essence of America: the struggle, the dream, the history, the myths, and the glorious diversity of the American landscape.

“This Land is Your Land,” considered by some, such as Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello as the original protest song, initially included verses that condemned social inequality and private property: “In the squares of the city, in the shadow of a steeple/By the relief office, I saw my people/As they stood there hungry, I stood there asking/Is this land made for you and me?”

Pete Seeger and Bruce Springsteen sang these missing verses at the Obama inauguration and the audience, including filmmaker George Lucas, joined in. Of course, not participating along with Pete Seeger is the equivalent of folkie blasphemy. Tom Morello has been known to sing these verses at recent Occupy Wall Street gatherings.

But the song’s message that many of us learned in elementary school was toned down and the tame version has become somewhat of an unofficial national anthem. The song captures the landscape of America in its verses – “from California to the New York Island” - and is sung by countless children across the U.S. every year.

In the course of his life, ended too soon at the age of 55 (following a long and tragic battle with Huntington’s Disease), Guthrie wrote nearly 3,000 song lyrics, in addition to many other creative works, including the books Bound for Glory and Pastures of Plenty. He was a champion of the American labor movement, writing memorable songs such as “Union Maid” and “Ludlow Massacre,” a historian who documented America from the days of the Old West through the Depression Era, a preacher who wrote songs about faith and religion, with songs about Hanukkah and Jesus Christ, and a booming, nasally voice for the downtrodden.

If Guthrie were alive today, he would be turning 100 years old on July 14, 2012, and there are festivals and events across the country celebrating his achievements and contributions to America on this, his centennial year. Many activists today would like to believe that if he were still around, Guthrie would be traveling on, speaking the truth in a world filled with lies, opening peoples’ eyes to the contradictions and injustices that abound, and giving hope to the hopeless, not unlike his friend and contemporary, Pete Seeger, who at 93 years old still uses his voice as a beacon of truth, hope, and change.

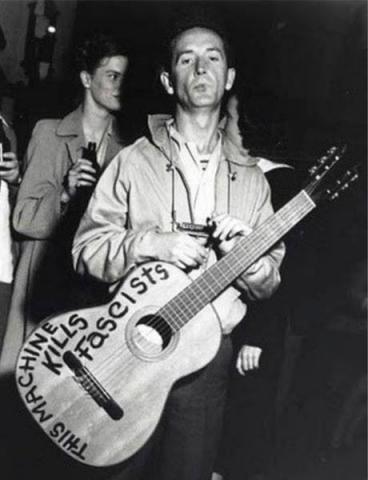

The world is still broken, though it has changed, in some ways for better – namely greater racial and gender equality – and in some ways for worse: It is an America of corporatization, anti-unionism, two controversial wars, the greatest financial crisis since the Great Depression, and the greatest gap between rich and poor that this country has ever known. Embodied largely by the fragile Occupy Movement, people are fighting for change and musicians are still rising up against the world, heralding the promise of hope after the struggle. Tom Morello, Bruce Springsteen, Arlo Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, Todd Snider and countless others – some better known than others – carry on the fight with their guitars and banjos, machines that “Kill Fascists” and surround “Hate and Force[s] it to Surrender.”

Even without Guthrie with us on this journey of life, his legacy continues on – from the folk revival of the 1960s, to the Mermaid Avenue recordings of Wilco and Billy Bragg, to little children singing his songs year after year in schoolrooms across the country, to his children and grandchildren that continue in his footsteps, to protest singers and truth-tellers of a new era.

His powerful legacy will likely carry on long after our lives have ended. The songs of Woody Guthrie were, as Steinbeck says, about the American spirit. Guthrie caught that spirit, that strong, hard will, and immortalized it. Years after his death, in celebration of his birth, we can only imagine that this spirit, strong as ever, will continue on, carried by generations to come. The spirit of Guthrie, his message and legacy have been passed on like the Olympic torch, and new fires are kindled daily by the spark Guthrie caught and nurtured into a raging fire.

Guthrie’s cultural legacy can best be captured in his own words. In “Tom Joad,” echoing the speech of Steinbeck’s literary hero, Guthrie sings: “Ever'body might be just one big soul, Well it looks that a-way to me/Everywhere that you look, in the day or night, That's where I'm a-gonna be, Ma/That's where I'm a-gonna be. Wherever little children are hungry and cry, Wherever people ain't free/Wherever men are fightin' for their rights, That's where I'm a-gonna be, Ma/That's where I'm a-gonna be.”

Woody Guthrie offered us hope when it was most needed, and that’s a powerful thing in a broken world - a promise that if we work together, we can, maybe, fix things.

Guthrie may be long gone, but he is certainly not forgotten. As Guthrie’s friend Pete Seeger writes in a foreword to Bound for Glory, “Woody will never die, as long as there are people who like to sing his songs.” In that case, I think we can rest assured that Guthrie’s legacy and influence will live for at least another one hundred years.

Author Bio:

Benjamin Wright is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

Photo: Larry Pieniazek (Flickr, Creative Commons)