The Buffett Rule As Rorschach Test (and the Party Thought Disorders It Reveals)

When President Obama discussed the seemingly forgotten Buffett Rule during a Florida stump speech on April 10, he reintroduced a fascinating prism through which to view the impending presidential race. In his speech, Obama explained that "the share of our national income going to the top 1 percent has climbed to levels we haven’t seen since the 1920s. The folks who are benefiting from this are paying taxes at one of the lowest rates in 50 years.”

Yes, the egregious income inequality between wealthy Americans and everyone else living in this country is important. It's not just a major wedge for this political race; it's the defining storyline in our country right now. As Obama and his campaign team know, the Buffett Rule -- officially the Paying a Fair Share Act -- is a powerful symbol of many Americans' desire for economic justice and reprisal against the richest 1 percent that has arguably cached the country's wealth for itself. So it's only rational that Obama would bring it into focus as the primaries shift to the two-man race for the presidency.

Alas, when the Paying a Fair Share Act went to a Senate vote on April 16, it was stonewalled by the Republican Party and fell nine votes short of the 60 required to open debate.

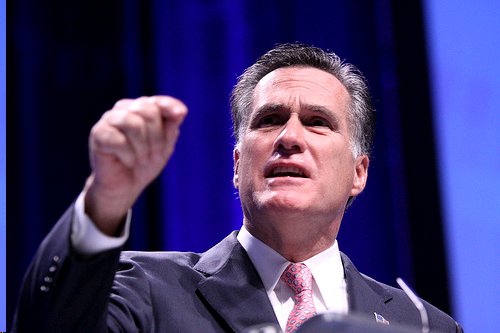

But more important than the act itself is the way both parties are fighting to shape how it sits in the national consciousness. Is the only power it wields symbolic, therefore making it just a Democratic campaign ploy to demonize de facto Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney? Or is it the opening gambit of a larger strategy to finally reclaim this country for, well, the 99 percent?

The proposed law is a bona fide Rorschach test for both parties, as they see what they want to see in it and even (in the GOP's case) associate desired realities onto the seemingly straightforward proposal. Many Republicans are calling it a "show bill." It's true that in presidential campaigns, the reality of legislation and the projected fantasy of policy and platform are often indistinguishable. But it's worth noting that in his State of the Union address in January, Obama declared that "Tax reform should follow the Buffett Rule." Such a progression would take at least a few years -- the same few years that both parties are now tussling for.

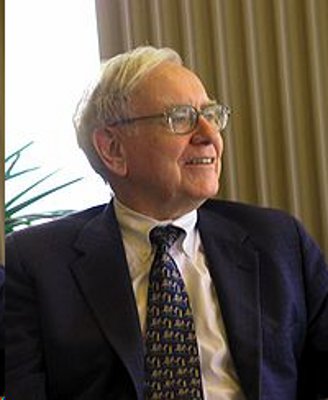

The Buffett Rule was proposed by President Obama in 2011 in an effort to both reduce the income gap and help relieve the astronomical deficit. Briefly, the law would force all Americans making more than $1 million a year to pay a minimum income tax of 30 percent. Its catchy moniker comes from billionaire investor Warren Buffet, who famously revealed to the world that he pays a lower tax rate than his secretary. Like many affluent Americans, Buffett collects most of his income from capital gains, which are taxed at a maximum rate of 15 percent. Conversely, salaries and wages are taxed at a rate between 15-35 percent for most earners. By any objective interpretation, this part of the tax code exorbitantly favors the super-rich.

Even after the Buffett Rule was blocked by the Senate, Democrats insisted they would continue to aggressively push for its passage. After all, this is an election year, and the Buffett Rule is far more than just potential legislation; it is a stark line in the sand drawn between the two candidates. It has also presented a unique opportunity for both parties to impose their own Fata Morganas on a bill, shifting and distorting the proposal's implications to their advantage.

What follows is how the Democrats see the bill and how they wish it to be seen. The main connotation of the Buffett Rule is vivid and requires little manipulative effort. Obama's inevitable Republican opponent, Mitt Romney, is a poster child for affluent advantage in America almost to the point of caricature. Over the past two years, Romney has earned $45 million and paid an average income tax somewhere between 14 and 15 percent in that period. This means that Romney has been taxed at a rate comparable to wage and salary earners making annual incomes between $8,376 and $34,500 during that same period. Of course, as he is wont to do, Obama is more tactful than to fill his speeches with these damning statistics. But for most the message is clear.

The president and his party are also conveying their ideological position going forward: Income inequality is a real crisis that must be combated. This grappling for a redistribution of economic opportunity and mobility will come in incremental phases if necessary, but come it must. Democrats know that at this point, the Buffett Rule is more emblematic than pragmatic (as opponents of the bill mercilessly harp on), but if they can't get this passed, then surely more substantial tax reforms would face an early KO in the Senate. Most of all, the underlying thought process of Obama and Democrats is that while the Paying a Fair Share Act may not impact the deficit, create jobs, or stimulate the economy, it is the one obvious action we can take to begin to reverse a trend where our government legislatively favors the rich.

Republicans claim to see something dramatically different in the inkblot. When prompted to discuss the proposal -- or just haranguing of their own volition -- they will unleash myriad reasons that it is either ill-timed, hazardous, or simply unimportant: The Buffett Rule will do nothing to tangibly improve the deficit; it won't help soaring gas prices; it could incite a cataclysmic asset selloff; and perhaps their favorite, it could potentially hurt job growth.

The GOP sees all sorts of terrifying possibilities in the Buffett Rule; their imagination is foreboding and paranoiac. At least that's what they want voters and political news junkies to think they think.

Then there is the accusation of class warfare: By proposing to make the tax code more equitable across all income brackets, Obama is instigating some sort of imaginary rhetorical war between the middle and upper classes. But when you think about it, is there anything wrong with rousing the vast majority of Americans toward a sense of empowerment over their economic futures? So "class warfare" is actually just a catchy, incendiary phrase that is only potent if no one takes the time to understand what it means in the political context that it appears.

Nonetheless, the buzzphrase has thrived during the Buffett Rule's media arc. That's because the Republican Party has become a proficient master at interpreting Obama's politics however it pleases and holding up a mirror to that distortion for the media (and consequently everyone else) to see. If in the Buffett Rule, Republicans see a fire-breathing hydra hell-bent on the destruction of our economy, jobs, and civil peace, then soon we will see it too.

So then the Buffett Rule exemplifies the crisis of perspective that is damaging our politics. How can average citizens approach potential legislation objectively when Republicans, and to a lesser extent Democrats, are relentlessly subjectifying them like so many dueling sorcerers casting illusion spells? They can only try. And the best effort we can muster to look at the Paying a Fair Share Act without party prejudice is to see it as a step in the direction of what Obama called "economic fairness."

The law would only recoup about $5 billion a year for the government and thus be hardly a nuisance to the sleeping giant deficit. But it might make tax reform (including ending the Bush tax cuts) and the issue of income inequality more accepted as major issues for America's future. As Obama understands, we have to start somewhere to reverse the income gap.

Author Bio:

Mike Mariani, a Highbrow Magazine contributor, is an adjunct English professor and freelance writer.

Photos: Mitt Romney (Gage Skidmore, Flickr); Warren Buffet (Wikipedia)