Author Thomas Mallon Revisits the Watergate Scandal in His New Novel

Watergate

By Thomas Mallon

Pantheon, 429 pages

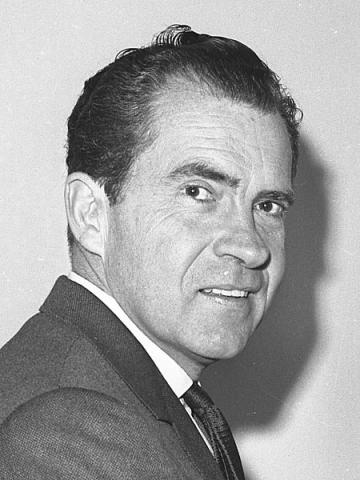

If there was ever a so-called “great man” with failure hardwired in his DNA, it was Richard Nixon. From his turbulent vice-presidency under Dwight D. Eisenhower to his failed attempts to succeed him as president or even become governor of California (“You won’t have Nixon to kick around anymore”), he seemed always embroiled in conflicts, many of them self-inflicted.

For veteran Nixon-watchers, his resignation from the presidency in 1974 as a result of the Watergate scandal came as little surprise—and, to many, as well-deserved justice.

Countless pages have been written about Nixon’s downfall, but novelist Thomas Mallon explores this episode through the prism of a multitude of characters caught in the scandal’s wake. Mallon sets himself a near-impossible goal—to write a novel about real-life people (some dead, some still living) who, by and large, lived on the fringes of this earthshaking event, and make it work.

Characters in the comic imbroglio include Fred LaRue, bagman for the Committee to Re-Elect the President, and Dorothy Hunt, the strong-willed wife of convicted Watergate burglar Howard Hunt, Nixon’s secretary Rose Mary Woods (entangled in the famous “18-minute gap” in a crucial White House tape-recording) and the president himself. First Lady Pat Nixon, for whom Mallon invents a fictional affair, and many others also get swept up in the turmoil.

For readers of a certain age, the swirl of events in Watergate will unearth memories of a time when the nation, still traumatized by the Vietnam War, saw a president crippled by what even his supporters saw as a “third-rate burglary.”

Mallon does a good job of capturing some of the D.C. insider frenzy of the time, though without recounting the crucial events themselves. The break-in at the Watergate complex is one of many incidents described after the fact. The author’s focus stays fixed on the effects of the Nixon administration’s many wrongdoings, rather than the wrongdoings themselves.

It’s a tricky narrative strategy, relying as it does on a reader’s knowledge of that ancient time. (For many younger readers, anything as far back as the 1970s might as well have occurred in the Mesozoic era.) In fact, it seems likely that those unfamiliar with that time will find much of this story bewildering, if not incomprehensible at times. It was bewildering enough to live through, since the Watergate burglars’ efforts to sabotage the Democratic Party in 1972 proved irrelevant after the Republicans’ massive electoral win in November. The illegal acts and botched cover-up that brought Nixon down need never have occurred—except that, in an atmosphere of deceit, larceny and outright criminality, it was almost guaranteed to happen. "The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars / But in ourselves …"

To accommodate our lack of awareness of specific events of that era, Mallon is obliged to spoon-feed information through the characters’ mouths. Unlikely dialogue sags under the weight of the exposition it’s forced to carry, as when Nixon discusses the timing of the selection of Elliot Richardson as new Secretary of Defense:

“I want to hold the announcement—and I mean it, no leaks—for about a week. Maybe by then we’ll get the damned peace settlement wrapped up. When we present you to the press, I’d like their questions to be about what comes after Vietnam, instead of all about whether Congress is going to cut off funds for the goddamned war.” He continued musing: “The press are always trapped in the past. Like their asking Ziegler if all the personnel shake-ups have anything to do with Watergate. I mean, for Christ’s sake. The only way we’re going to get hold of and squeeze the career bureaucracy—which is ninety percent Democrats, in every department—is to reorganize the whole political layer on top of it. Things are no different at the Pentagon. Christ, Elliot, some of these generals have more screwed-up ideas than your sociologists over at HEW. I’m counting on you to cut their budgets without losing the Joint Chiefs’ support of SALT.”

In the end, by choosing to avoid the high drama of the break-in, cover-up and impeachment proceedings, Watergate relies on the inner lives of (mostly) secondary characters for its narrative thrust and rarely seems to catch fire.

Author Bio:

Lee Polevoi is Highbrow Magazine’s chief book critic.

For Highbrow Magazine

Photo credit: UCLA Archives (Wikipedia, Creative Commons)