Rene Magritte—Magician of Dreams and Perception

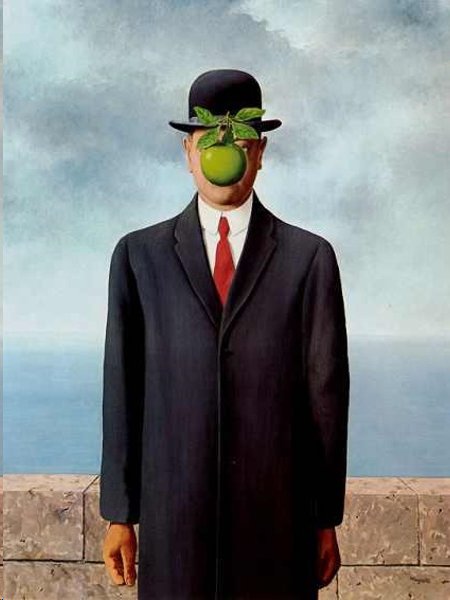

A blue bow, a bowler hat, a candle, a bird, a vanity mirror and an apple—commonplace objects, right? Think again. If you visit the Museum of Modern Art’s current exhibit, Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938, expecting to be comforted by the familiar, you are in for a rude surprise. These items are part of a painting entitled The Daring Sleeper and are framed below a sleeping figure of a man. The Belgian-born surrealist painter (November 21, 1898-August 15, 1967) had more inside his infamous black bowler hat than you ever dreamed of and if you dare to look closely, you will never dream the same way again.

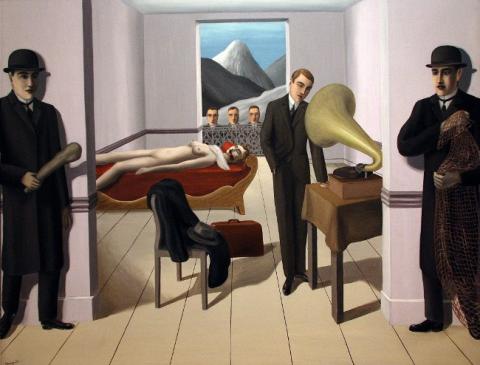

From the moment you step inside the sixth floor’s main entryway, you are confronted by The Menaced Assassin, one of Rene Magritte’s most massive and mysterious paintings. There are actually two assassins (don’t try to rationalize the titles), one hiding on each side of the canvas foreground, just out of view of the scene of the crime. A nude and bloodied woman is draped across a settee, while another man (a detective perhaps), briefcase and overcoat placed on a nearby chair, bends over a Victrola. Magritte lifted the idea from a popular crime film of the day, wanting to transpose onto the canvas the mystery inherent in the film. But this is no ordinary recreation. Three identical male heads peer into the room through a background window. We are, to be sure, in Magritte’s world and not the filmmaker’s.

It’s a disarming pictorial display, and one which was part of Magritte’s first major exhibit at the Galerie le Centaure in Brussels in 1927. Executed with a finesse and economy of means that set the artist apart from surrealist compatriots of the fantastic and bizarre—like Max Ernst and Salvadore Dali—it became a precursor for many of his most disturbing images to come. Masterful depiction aside, the exhibit was not a success and depressed by the outcome, Magritte moved to Paris for the next three years. It was a wise move, placing the painter front and center with philosopher and critic Andre Breton’s surrealist group.

Undoubtedly, it was a perfect match of sensibilities at the time. As Breton defined surrealism in William S. Rubin’s definitive publication, Dada and Surrealist Art, “we mean to designate a certain psychic automatism that corresponds rather closely to the state of dreaming.”

Even if some young viewers may not be quick to recognize this artist in the historical context of his times, MOMA’s curator Anne Umlaud has mounted an exhibit of Magritte’s most brilliant and prolific period. We are first introduced to some highly arresting black and white photographs of the movement’s major players. In one photograph the group is pictured with eyes closed, obviously symbolizing their disavowal of the external world. In another portrait of the artist, he poses himself next to a painting of his double, who appears to disappear into a brick wall. There are also a series of publications on display, including the seminal periodical, la revolutions surrealiste (1924-1929). But it is the 80 paintings and readymade sculptural objects that grab the eye.

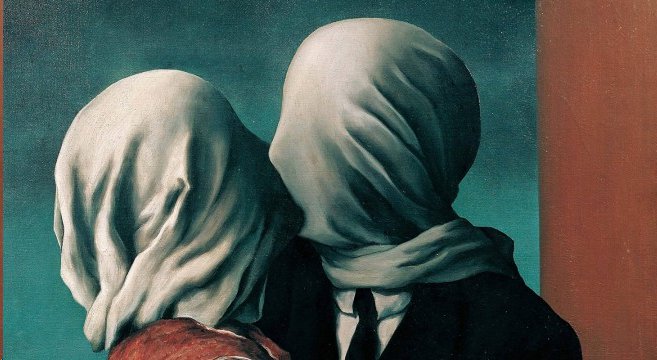

A particularly grisly painting from the same year as The Menaced Assassin, is Young Girl Eating a Bird (Pleasure). This bloody depiction leaves no question, according to the wall notes, that eros and thanatos—the battle between life and death-- are often elemental subjects of our dreams, or more aptly, our nightmares. No surprise that some viewers move quickly on to The Lovers, from 1928, which pictures a man and woman kissing but with heads concealed underneath heavy swaths of white cloth.

What gives a startling resonance to this painting is the fact that Magritte’s mother, a former milliner before her marriage to the tailor Leopold Magritte, attempted suicide several times. When the artist was 13, she drowned herself in a nearby river, her dress covering her face upon discovery. Whether or not the boy actually witnessed this troublesome image may not be proven, but several paintings from this period reveal faces covered with cloth. It is the exquisitely rendered contour of the wrapped figures in The Lovers and the simplicity of the overall composition that give it power.

Another smaller, wonderfully executed painting is a portrait of a woman, Discovery, wherein the nude figure is morphing into another substance, portions of her shoulder and buttocks and breast clearly no longer skin but grains of wood. The accompanying notes in Magritte’s words describe his own discovery in the ability of things to “become gradually something else, an object merging into an object other than itself.” In this way, he saw “no break between the two substances” and the eye would have to think about the image in a profoundly different way.

In The False Mirror a giant eye confronts the viewer. Where the whites of the eye would be positioned, there is the transparency of clouds and blue sky. If we are to believe his title, is Magritte telling us that we should not believe the old adage that “the eyes are the windows to the soul?” Maybe the message is simply in the void beyond.

Titles for Magritte (like the Dadaists before him) are beside the point and were often arrived at after the completion of a certain work—an arbitrary and playful exercise meant to prevent the onlooker from conveying any meaning to the enterprise at all. Take for example, The End of Contemplation. A head is pictured in profile, but the profile has been neatly shredded, like a child’s paper cutout exercise. In Denizens of the River, a headless figure in a dinner jacket with what appears to be a pipe fitting for a neck takes center stage, while on the left a leg disappears off canvas. Making a rational connection between the image and the naming is a futile if not laughable act.

Disembodied parts of the human anatomy are always unsettling and Luis Bunuel, an early surrealist filmmaker, understood this all too well. In his early film, Le Chien Andalou, a woman’s eye is sliced with a razor blade—unsettling to say the least. Magritte understood that we may be so much more than our physical bodies or simply a stray assortment of segments to be taken as a grain of salt. The Rape portrays a woman’s body featuring the pubic hair as mouth and her breasts as eyes. She is reduced to her body parts and as a consequence, her facial expressions—her individuality—is inconsequential. Is this the supposition we are expected to make? Magritte is a puzzler. He doesn’t expect his riddles to be solved, but we try nevertheless.

The strongest public awareness of Magritte’s work burgeoned full-force in the Pop Art phenomenon of the 1960s. His own unique graphic sensibility of the everyday world influenced works by painters Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Duane Michaels and Ed Ruscha, among others. Andrea K. Scott, in her September 23 review in the New Yorker, claims that Magritte’s art “has been hijacked for designs ranging from the Beatles’ record label to a Volkswagen ad to a bowler-hat light fixture.” When Los Angeles Contemporary Museum of Art curator Lynn Zelvansky interviewed Ed Ruscha for the LACMA website, Ruscha described his favorite Magritte painting, Time Transfixed, (on view in the current MOMA exhibit) without really knowing why he was transfixed:

“… There is the unlikeliness of it. In our daily lives we don't see trains coming out of fireplaces. So that's a number one good thing for that picture. There's an unreality, or a misreality there. And then there's the reality of the exhaust that the train is pushing out. The smoke that comes out of the engine is going back up the fireplace, and that brings you to some sort of rigorous truth. I mean, isn't smoke supposed to go up fireplaces?”

This struggle between the unreality and the reality of the painting is for Ruscha “the right kind of struggle to make a great picture.”

There is a 1967 photo portrait of Magritte by Lothar Wolleh, which has the artist standing in front of one of his iconic paintings. It’s a headless Magritte in typical business man’s attire, with the familiar black bowler hat floating atop the invisible head. Perhaps Magritte was the ultimate magician. His hat held for his audience a thousand mysteries, a thousand dreams and deceptions, but the magician himself was not to be found.

(Magritte: The Mystery of the Ordinary, 1926-1938, is on view at The Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53 Street, New York, NY 10019-5497, 212-708-9400 until January 12, 2014.)

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.