Elections 2012: A Lollapalooza of Lies

Lies have been with us Homo Sapiens since back when Jesus wore sandals, as my Grandpa Ben used to say. They are as ancient as sand and rocks and caves. I can imagine Neanderthals of the Pleistocene era lying about exactly who among the hairy-backed knuckle-scrapers first figured out that roots dug up from the earth ought to be cooked prior to consumption.

Since there is no science in the matter, I would offer my subjective view that politics, money, and sex constitutes the holy trinity of untruth. And since the long and deceitful presidential election campaign is still ringing in our minds—like an especially annoying car alarm—let us consider the political arena.

Not for the first time in the history of American presidential contests, crass calumniation was at center-stage in this year’s production of the quadrennial spectacle.

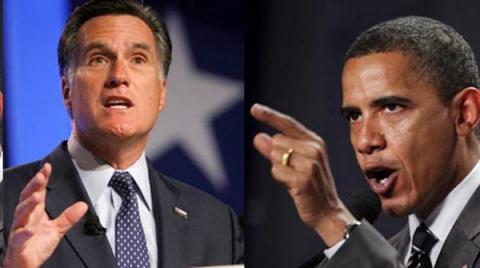

Throughout the summer and autumn months, “liar” was the once seldom heard pejorative mustered by manned-up Democrats in describing Willard Mitt Romney, now twice-failed as a Republican hopeful, along with his awkward running mate, Congressman Paul Ryan. A few examples:

• “Plenty of people have pointed out what a liar Mitt Romney is,” said Brad Woodhouse, communications director of the Democratic National Committee, in an interview with The Week magazine.

• At a press conference aboard Air Force One, David Plouffe, senior adviser to President Barack Obama, said Mr. Romney “lie[d] to fifty million Americans,” according to the Wall Street Journal.

• In a September 2 appearance on CBS-Television’s “Face the Nation,” Stephanie Cutter, deputy campaign manager for Mr. Obama’s successful re-election effort, said Republicans in general “think lying is a virtue.”

• Remarkably, a Fox News contributor was permitted to indict Mr. Ryan for falsity of historic proportion when he accepted the vice-presidential nomination at last August’s Republican National Convention in Florida. “Ryan’s speech,” wrote Sally Kohn for the Fox blog, “was an apparent attempt to set the world record for the greatest number of blatant lies and misrepresentations slipped into a single political speech.”

Ever decorous—and mindful of the comity expected of an incumbent White House tenant—Barack Obama did not himself utter the L-word, though he came daringly close. Republicans, meanwhile, went about lying with their customary abandon. They slandered the president as, variously and sometimes all at once, Kenyan-born (Donald Trump’s meme); an apologist for Islamic terrorism (Mr. Romney himself, in accusing the president of sympathizing with Benghazi murderers); a secret homosexual (Jerome Corsi, a popular conspiracy theorist and member of the Romney campaign press corps); and a heretic of possibly Christian persuasion who, in supporting same-sex marriage, has “shaken his fist at God” (the Rev. Franklin Graham, son of Billy), thereby expediting the American apocalypse.

Daniel Henninger, the Wall Street Journal’s deputy editorial page director and Fox News commentator, confined his shock—shock!—to use of the word “liar” by Democrats. “’Liar,’” he complained in a Journal essay, “is a potent and ugly word with a sleazy political pedigree.

Mr. Henninger added, “Explicitly calling someone a ‘liar’ is—or used to be—a serious and rare charge, in or out of politics. It is a loaded word. It crosses a line. ‘Liar’ suggests bad faith and conscious duplicity—a total, cynical falsity.”

Lying, a universal truth

Lest anyone believe that untruths are more plentiful in the United States than anywhere else, or peculiar to political stratagems, New York psychiatrist Gail Saltz makes the case for global lying as a natural element of human physiology—for better and for worse.

“Everybody lies,” wrote Dr. Saltz in a disquisition on the subject for NBCNews.com. “We start lying at around the age four to five, when children gain an awareness of the use and power of language. This first lying is not malicious, but rather to find out, or test, what can be manipulated in a child’s environment.”

Pathological liars—those “compelled to lie about the small and large stuff,” according to the Saltz calculation—represent the dark side of mendacity’s moon. They are the worst of lying’s lot, for they vandalize an “unspoken agreement to treat others as we would like to be treated,” wrote Dr. Saltz.

She added, “Serious deception often makes it impossible for us to trust another person again. …If the truth only comes out once it is forced, repair of trust is far less likely.”

Todd Gitlin, a professor of sociology at Columbia University and chairman of its Ph.D. program in communications, likewise takes the universalist view of lying. But his deepest appreciation is for the American variety.

“I don’t know if lying is any more prevalent in the U.S. than elsewhere,” he told me, “but there is certainly a hoary tradition of it here. Think of ‘tall tales,’ and ‘confidence men,’ and African American ‘toasts’ [the origin of hip-hop “boasts”).

“If we do this sort of thing more than others do, it would probably be because rugged individualism encourages Americans to think that each of [us] invents our own reality,” he said further in our conversation. “The hunger to smoke out lies comes from a Puritan tradition. The hunger to tell them comes from overconfidence that we are little gods.”

Neither Professor Gitlin nor any other sociologist or historian or psychologist I consulted was aware of any published scholarship that compares American lies to those of other nation-states, or cultures. None. People will have their suspicions, however, about their countrymen versus The Other. I have mine; you have yours. Which constitutes prejudice, which is a whopper.

Lying = Money (& Pretty Delusions)

What would Madison Avenue do without lies?

Lies encourage necessary commerce. Here now, we enter the art of lying for money. In support of lying for money, via advertising, the advertising industry creates lovely lies at the intersection of fiction and fact—providing us inspiration of all sorts and strength in harmless delusion. Prettier lies yet affirm our appearance, our behavior, our exquisite taste, and our guilty pleasures—all monetized in the form of consumer products, many of which are unnecessary.

The most artful lies of Mad Men are nuanced. Others are sold softly, others bluntly.

A 17th century French dramatist by the name of Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, aka Molière, is perhaps the father of the soft sell. “People can be induced to swallow anything,” he famously said, “provided it is sufficiently seasoned with praise.”

The hard sell is the territory of my friend and one-time employer Jack Avrett, the late president of the New York ad agency Avrett, Free & Ginsberg.

“Tommy,” he asked me one day, “would you like to know how come I’m so damn rich?”

Indeed, said I.

“Do you have any idea how easy it is to sell Americans anything?”

To this, I responded, learnedly, “Well, sir, working in Mad Avenue has provided me with a fairly good education in that area.”

“Now, Tommy, there are two kinds of people in the advertising dodge: smart people, and geniuses. The smart ones know what smart people want. Geniuses know what stupid people want.

“I’m a genius,” Jack declared. “And I get an override on a whole lot of things that stupid people buy.”

Chronicles of grift

Human stupidity—naïveté, if you prefer, with a dash of avarice: such qualities clothe us all, in sizes ranging from petite to plus—is fertile ground for liars. Always was, and forever shall be, this match of mark and con. Never mind the nationality of either player. Again, we are in money territory here.

The Scotsman Gregor MacGregor (1786-1845) was a liar of the first rank. Togged out in a military tunic of black twill with an oval-shaped scarlet breastplate, accompanied by stiff collar and epaulets of gold satin roping, he introduced himself to the royalty and lesser élite of Europe as the “Cacique of Poyais.” The tribal chief of Poyais, he explained, that being a region west of Argentina chockfull of gold nuggets sparkling in mountain streams and minerals in the plains aching to be mined. Mr. MacGregor convinced the lords and ladies to invest in lucrative developments far across the seas in Poyais. Alas, no one on the South American continent had ever heard of such a place.

Victor Lustig (1890-1947) was a multilingual cosmopolite born in what was once known as the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He began his career in lying as inventor of the so-called money-box scheme. He would demonstrate the amazing capability of a small photographic crank box of his making, stuffed with stacks of currency-sized paper. An exterior top mount of thick glass snugged an American $100 note. A hand crank operated on the side. As Herr Lustig turned the crank, a duplicate greenback was ever so slowly copied. (A genuine greenback, of course, that lay upon the stack of blanks.) All the while, Herr Lustig lamented the key shortcoming of his magical device: It took several hours to produce a bill. But, sensing huge profits in exchange for a relatively small investment of time, buyers snatched up money-boxes as fast as Herr Lustig could assemble the flimsy things—minus the genuine currency, of course. The price for a money-box was often as high as $30,000.

Carlo Pietro Giovanni Guglielmo Tebaldo Ponzi (1882-1949)—aka Charles Ponzi, aka Charles Ponei, aka Charles P. Bianchi—fled poverty in Italy as a teenager, arriving in Boston in 1903 with the equivalent of two dollars in his pocket. His get-rich-quick impulse was excited by newspaper accounts of a small-time Brooklyn swindler named William F. Miller. Mr. Ponzi perfected Mr. Miller’s scheme, thus introducing an early incarnation of arbitrage, one that is not so different than today’s Wall Street contrivance. He raised loads of cash from naïve, stupid, greedy investors in New England during the 1920s, on the basis of a most attractive lie: a 50 percent profit within 90 days. The funds raised bought discounted postal reply coupons in Europe for redemption at face value in the U.S. and Canada. For a time, the formula worked: One mark realized a fast-shuffle profit by way of “investment” money ponied up by a successor mark, and so on and so forth until the unsustainable arrangement collapsed, by which time Mr. Ponzi would become either Mr. Ponei or Mr. Bianchi.

Bernard Lawrence “Bernie” Madoff was born in New York City in 1938, the son of a housewife and plumber. He will die in a federal penitentiary, situated in a desolate stretch of rural Minnesota, well before the end of his century-and-a-half prison sentence, imposed in 2009 when he was found guilty committing the largest financial fraud in world history. A student of Mr. Ponzi’s slick lies, Mr. Madoff made off with an estimated $65 billion—much of it bilked from endowment funds that provided operating principal for Jewish charities and educational institutions, on whose boards he sat.

The loving pretense

Sex! In the lying context, there is something known the “rule of three,” as applied to the sexually coy and the sexually boastful, in accordance with respective gender. It works like this: attach a multiple of three to the number of sexual partners claimed by women; divide by three the number of conquests alleged by men.

“Everybody lies about sex,” asserted comedian Janeane Garofalo. This truism earned sustained laughter from studio audience members during a June 2011 taping of HBO’s “Real Time with Bill Maher.” The remark was made in defense of former New York Congressman Anthony Weiner, whose email account earlier in that year posted self-made photos of his aroused gonads bursting beneath his tightie-whities.

The science fiction writer Robert Heinlein (1907-1988) said precisely the same, in his book “Time Enough for Love.” In fact, says filmmaker/comedian Woody Allen, “Without lies, there would be no sex.”

The late Jim Morrison (1943-1971), lead singer of The Doors, was known among his women friends and brief acquaintances by the none-too-subtle nicknames “Mr. Mojo Risin’” and “Lizard King.” Mr. Morrison was also an aphorist. His studied conclusion, the result of numerous trysts: “Most people love you for who you pretend to be. To keep their love, you keep pretending—performing.”

Mr. Morrison added, “You get to love your pretense. It’s true. We’re locked in an image, an act.”

Lies, aka Civility, aka Art, aka Truth

“Of course I lie to people,” once said the colorful and charitable Denis Charles Pratt, aka Quentin Crisp (1908-1999), the British author, actor, nude model, and raconteur of proudly effeminate tendency. “But I lie altruistically—for our mutual good. The lie is the basic building block of good manners. That may seem mildly shocking to a moralist—but then, what isn’t?”

Mr. Crisp lived out his latter years in a tiny apartment with giant insects on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, at the time a dicey residential option—especially so for a man who paraded daily through its streets with hair pinned up in a bun and dyed in violet to complement his mascara, long painted fingernails, and a peacock feather bouncing atop a jauntily-placed fedora.

His contemporary was Clare Booth Luce (1903-1987), playwright turned political light—a Franklin Roosevelt liberal who converted to conservatism, first the mild brand of Dwight Eisenhower, who appointed her ambassador to Italy in 1952, and finally the more strident stuff of Ronald Reagan. Ms. Luce was something of a journalist, but far better remembered for her magazine fiction and stage plays, the latter of which earned a place in the pantheon of Broadway.

“Lying increases the creative faculties,” she once told a reporter for the New York Herald-Tribune. “Lying increases the creative faculties, expands the ego, and lessens the friction of social contacts.”

Ms. Luce was on to one of the ironies of philosophical realization: lying and truthing could not exist, one without the other.

The movie version of Ernest Hemingway’s “Islands in the Stream,” as in the novel, ends with a deathbed scene in which George C. Scott in the role of hero Thomas Hudson says in last breath, “I know now, there’s no one thing that’s true. It’s all true.”

I blush as I quote a line of dialogue from “Drown All the Dogs,” a novel of mine published here and abroad in 1994: “Every lie is a truth somewhere in time.”

Back in the day

Should lies of the blessedly ended presidential campaign of 2011-12 linger shockingly in mind, consider the pungency of yore:

• John Adams and Thomas Jefferson were opposing candidates in the campaigns of 1796 and 1800. In the first square-off, the victorious Mr. Adams claimed that Mr. Jefferson was a “coward” for his failure to take up arms during the revolutionary war, and Adams-friendly newspapers insisted that Mr. Jefferson was a champion of open marriage and prostitution. In the second race, a victorious Mr. Jefferson’s aides said President Adams had secretly sent a ship to England to retrieve a pair of mistresses, that Mr. Adams was plotting to abolish the newly minted Constitution to become “king of America.”

• During the election campaign of 1828, challenger Andrew Jackson’s partisans referred to President John Quincy Adams (son of the aforementioned Adams) as a “pimp,” in service to the czar of Russia during Mr. Adams’ earlier post as ambassador to the imperial court at St. Petersburg, and his wife as “born to bastardy.” Loyalists to President Adams, meanwhile, said Mr. Jackson, hero of the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812, engaged in cannibalism when his troops were stranded in swamplands.

• John C. Frémont (1813-1890) was the first presidential candidate of the new anti-slavery Republican Party and also tarred as a cannibal. Prior to a political career, Mr. Frémont was a highly decorated military officer and adventurer in the western states. His presidential bid in 1856 was scuttled when Democrat stalwarts allied with Franklin Pierce claimed that in 1848 Mr. Frémont consumed human flesh in the windswept San Juan mountains of Colorado.

• The Republican Party’s second presidential candidate, in the election of 1860, was Abraham Lincoln, an unhandsome man with unusually long arms. Newspaper cartoonists called him “the ape man.”

• In 1876, the Democratic candidate Samuel Tilden was called a “syphilis-plagued drunkard” by those rallied to the Republican candidacy of Rutherford B. Hayes. The Tilden side said Mr. Hayes had shot his mother with a pistol and stolen money from dead soldiers on Civil War battlefields.

Author Bio:

Thomas Adcock, a Highbrow Magazine contributor, is a journalist and author based in New York City.