New York's Ever-Changing Character: Creating a New City Experience

New York City today can shock those who remember the 1970s or 80s, or even the early 2000s. Viewed as a crime-laden center, it now boasts swaths of green and corner cafés. Several decades ago, the difference between suburbs and cities was stark. Suburbs had fancy shopping malls and were perceived as clean and safe; cities, slathered with graffiti, were dangerous. The flight of the middle class from New York, as well as many urban centers, was staunched. Today, parks ring the waterfronts, bike paths parallel auto lanes, and Whole Foods and Sephora nestle in every neighborhood. After complaining about dirt and crime for so long, are we really ready for the “suburban city”?

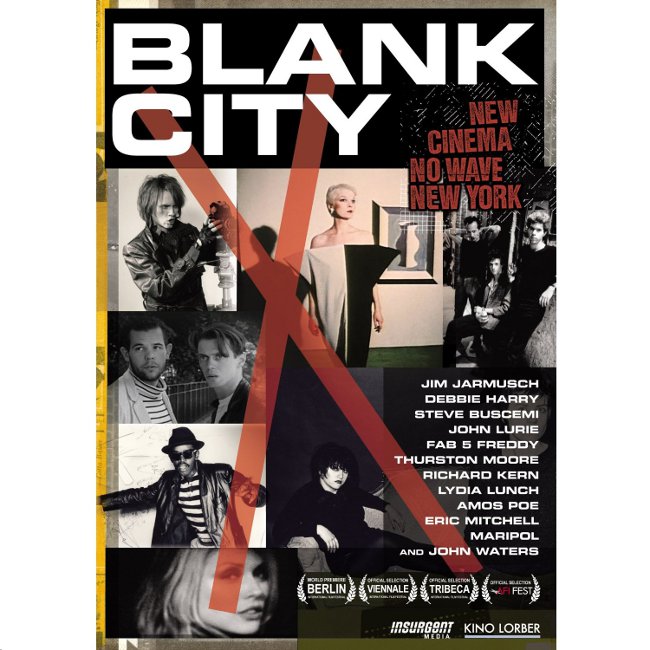

Blank City, a recent documentary about the New York indie movie scene during the late 1970s and early 80s, presented that time and place as a hotbed of creativity, teeming with people who thrived on poverty and survived on their talent. Able to make their way through the violence and abject tenement conditions until drugs, AIDS and rapacious landlords laid them low, filmmakers and artists recount their youth as a time of cheap rent and “transgressive” expression, an era when anything was possible. Jim Jarmusch and Steve Buscemi among others bemoan the cleaning up of the East Village and claim that creative energy was lost in this transformation. These reminiscences resemble those of veterans and the Depression-era raconteurs who look back at bad times and only see the good, ignoring that New York rent was never affordable (many of these actors were squatters) and many of their cohorts did not survive.

Their comments highlight the oft-spoken dichotomy that pits creativity, dirt and crime against clean and safe streets and boring affluence. Does equating a comfortable public life and national brands with gentrification mean that we believe that urban life is supposed to be difficult and dangerous? True, now artists wail that inexpensive space is scarce, the poor protest that they’re priced out of habitable apartments and everyone complains how expensive these changes have made the City.

Despite this recent recession, the public realm has been transformed: The City has stopped restricting and diminishing public spaces and started to embrace them. From the late 1960s and into the late 1990s, public space was abandoned or privatized. As Mayor John Lindsay declared that New York was “Fun City,” parks and the public realm were left to crumble. Residents and the City administration just gave up—vagrants were allowed to sleep in train stations and sidewalks were strewn with trash. To avoid maintaining these spaces on the public dime, developers were allowed to build higher and bigger by providing building setbacks which became desolate windswept plazas devoid of seating.

Fast forward to today, where in New York “traffic easing” measures create public street plazas furnished with café tables, licensed food trucks and bike lanes.* The first such plazas, in tourist-heavy areas such as Times and Herald Squares, were ridiculed in commentaries as being only for sightseers exhausted from unaccustomed walking and laden with shopping bags. Little by little, combined with bike lanes and traffic barriers, mini-plazas cropped up in more prosaic and workaday neighborhoods. It turned out that even New Yorkers enjoyed sitting at public café tables in the middle of the road. Some of this new openness can be attributed to the lowering of the crime rate: Sociologists and urban planners can debate forever which came first—enhanced public spaces or the feeling of safety.

This development arc is not restricted to New York. Philadelphia also started inserting promenades scattered with comfortable benches and street art along downtown tourist routes. Portland, Ore., stakes its claim as a livable city because of its walkability, access to public transportation and farmers markets. Now, it’s the rare city that lacks bike lanes, if only in the form of painted green strips.

I am conflicted by these developments. To decry parks and open space comes across as unseemly, however, they do change the character of our cites. I’m not talking about the nostalgia for the dark side of near-bankruptcy grunge that has become fashionable. Gone also are many of the small quirky stores in definable neighborhoods, replaced by big-boxes sporting national names that have popped up on streets where one previously only walked through, not window-shopped.

Some present-day developments are a little too precious for me. For example, as a pedestrian, I hate bikes because they inevitably try to run me over. But while I am dismissive of misused or empty bike lanes, I enjoy the new parks and public plazas and the ease with which the reconfigured intersections can now be navigated. These improvements have changed city life. The scene on the sidewalks in front of my apartment building on pleasant weekend mornings, unimaginable 15 years ago—whole families on bikes on their way to waterfront parks, weekday office-bound workers now heading for city dog runs, teenagers on skate boards or multi-generational families strolling with baby carriages—now resembles architectural renderings of healthy communities.

But apart from personal impressions, let’s acknowledge that these changes are redefining the essence of the American urban public realm: private cafes spill onto sidewalks, pedestrians no longer hurry through benchless plazas and inhospitable streets, but are encouraged to loll on whimsical seating next to fanciful bike racks. Bike rooms are the new de rigueur office and apartment building amenity. The 2012 urban street allows for commerce and individual private moments: Bernard Rudofsky’s 1969 book Streets for People: A Primer for Americans come to life—with the addition of cyclists and joggers, of course. In short, the public has reclaimed its rightful spot.

Many of the improvements cited above have been achieved with little money—merely changes in a few regulations, lots of green paint and some concrete barriers and metal café tables. Others require a large investment, such as the refurbishment of Grand Central Terminal and the transformation of once-abandoned industrial waterfronts or artifacts into continuous bands of green on land use maps. Nipping upon the heels of park development is the increase in real estate values and the gentrification of adjacent neighborhoods. Despite the shock of this result, it is a common occurrence noted since the establishment of Central Park and continuing today. New York City’s High Line, praised as an innovative restoration and recreation project, simultaneously created the newest high-rent district.

These developments are more complex than those envisioned when The Suburbanization of New York, a compilation of essays edited by Jerilou Hammett and Kingsley Hammett in 2007, was published by Princeton Architectural Press. Articles in that book recalled a New York synonymous with creativity, sophistication and a certain idiosyncratic chaos and bemoaned the concerted effort to sanitize it to lure back the middle and upper classes. At the time of publication, it appeared as if changes tended toward commercial homogenization—the “malling of the City”—that introduced big-box national chains and corporations that impinged upon neighborhood character. In the words of the Preface, “…New York is on its way to becoming a 'theme-park city,' where people can get the illusion of the urban experience…” Only five years or so ago, most gentrification consisted of the proliferation of private, corporate-owned stores, office buildings and amusement centers. It’s the transformation now of public space, especially areas for both active and passive recreation, that is creating a new city experience.

As I described in my book, Redeveloping Industrial Sites, this softening of the city is also happening in Europe. In America, this mechanism is presented as happenstance. However, Paris, among other cities, has specifically employed it to revive neighborhoods. Faced with the poorer eastern sector blighted with abandoned industrial parcels, the Parisian government created a master plan in which the development of parks and promenades on these abandoned properties was deliberately used to encourage the repopulation of that part of the city and ease the housing situation throughout the whole city. Now, as in New York and other American cities, areas previously homesteaded only by poor people or artists are new chic districts.

There is irony in the development of these parks and amenities, many of which were brought about by environmentalists and concerned urbanists. In trying to make the city more open and livable, they are making it more expensive, exclusive, and dare I say, suburban.

*A coalition of forces, spearheaded by cyclists, organized these developments under the name “Complete Streets” which calls for a public “right of way to enable safe access for all users…[to] make the street network better and safer for drivers, transit users, pedestrians, and bicyclists—making your town a better place to live.”

Author Bio:

Carol Berens, a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine, is an architect and writer in New York City. Her most recent book is Redeveloping Industrial Sites (2010, Wiley). She also writes for UrbDeZine, a website that revolves around urban design issues. Her website is www.carolberens.com.

Photo of High Line: Luis Guillermo Pineda Roda, Flickr

Photo of Central Park: Robert Garcia, Flickr