Lessons From the Failure of U.S. Propaganda in the Middle East

“After 70 years of broken western promises regarding Arab independence, it should not be surprising that the West is viewed with suspicion and hostility by the populations of the Middle East.” – Sheldon L. Richman, senior editor at the Cato Institute, two weeks after the start of the First Gulf War, August 1991

At the end of March 2010, the Obama administration issued a report, which provided an assessment of the nation’s strategic communications efforts and offered recommendations for a more nuanced approach to public diplomacy.

At the heart of the president's new framework is a profoundly simple concept that has nonetheless eluded successive U.S. administrations going back to the Eisenhower presidency.

Referred to in the report as “synchronization,” the concept is part of a two-pronged strategy for effective communication with foreign audiences, and is spelled out succinctly in the administration’s “National Framework for Strategic Communication.” The second prong is simply “deliberate communication and engagement.” Whereas the latter concept refers to a concrete methodology for engaging an audience, the more abstract notion of synchronization is concerned with what message is being sent and how the intended audience is receiving it.

According to the report, synchronization involves “coordinating words and deeds, including the active consideration of how our actions and policies will be interpreted by public audiences…” As such, “This understanding of strategic communication is driven by a recognition that what we do is often more important than what we say because actions have communicative value and send messages.” Or, put another way, “Every action taken by the United States government sends a message.”

What the president and his advisers are saying is that actions speak louder than words. It’s a concept any fifth grader can understand, but unfortunately a failure to appreciate and internalize this simple lesson has plagued U.S. public diplomacy efforts for more than half a century—nowhere more so than in the Middle East—and has been the focus of intense academic and practical scrutiny for the past two decades.

In the weeks and months following 9/11, the U.S. began a large-scale revival of propaganda in the Middle East. Public relations firms like the Rendon Group, Layalina Productions, Weber-Shandwick Worldwide, and Hill & Knowlton have all worked diligently to sell U.S. policy overseas, collectively garnering millions of dollars in government contracts and private financial support.

And yet, a decade later, the U.S. has made little headway in winning “hearts and minds” in the Middle East; on the contrary, anti-American sentiment is higher than ever. Eighty-five percent of Arabs describe their views of the United States as unfavorable, according to a 2010 poll by Zogby International, while nearly 90 percent are pessimistic about U.S. foreign policy in the Mideast, even if they have a favorable opinion of President Obama. Most tellingly, 80 percent of respondents to a 2009 poll by the same group related that they formed their view of the U.S. based on its policies, not its purported values.

This confirms what historians have known for years: the problem with U.S. public relations in the Middle East lies not in the quality of the product or its mode of transmittal, but in the disconnect between the message and audience perception. America continues to engage in a campaign of public diplomacy that is fundamentally at odds with its regional foreign policy. Specialists call this the “say-do gap,” and it has plagued British and American foreign-policy goals more than half a century.

Anna Tiedeman, author of “Branding America: An Examination of the U.S. Public Diplomacy Efforts After September 11, 2001, explains: “In marketing terms, the [U.S.’] brand experience did not match with the brand message. When a brand message consistently agrees with and reinforces the brand experience, a relationship can be built. If, on the other hand, the brand experience is not consistent with the message, it will backfire and lead to mistrust of the brand.”

If anything can be ascertained from President Obama’s call for synchronization, it’s that the administration is aware of this policy’s disconnect and, it would seem, is willing, if not ready, to address it. But to do so will require a monumental shift in policy, not the least of which would be a renewed commitment to Israeli-Palestinian peace. Whether the president and his State Department have the political will for such an undertaking remains to be seen, although it appears doubtful. As I write this, the President is soon to face an important test in how he handles the Palestinian Authority's decision to appeal to the United Nations for official state recognition. To date, President Obama has been working to dissuade the PA in this endeavor—although this is unlikely to work—and the U.S. has pledged to veto a vote in the 15-member UN Security Council even though Obama has backed the creation of a Palestinian state based on the 1967 borders (can anyone say, say-do gap?). This disconnect between words (support for Palestinian statehood) and deeds (the threatened veto) will deliver the Arab world an important message: The United States still doesn't get it.

A poll of Arab public opinion conducted last year by Zogby found that 64 percent of respondents see the Palestinian issue as the number-one factor influencing their opinion of the United States, compared to just 4 percent who chose the war in Afghanistan. More than half of respondents said that mediating a fair and balanced Palestinian-Israeli peace agreement is the single most important thing the U.S. could do to improve its image. Yet despite this overwhelming evidence, only 7 percent of Americans see Arab-Israeli peace as the top issue affecting U.S. relations with the Muslim world. Such a disparity underscores just how out of touch many of us still are when it comes to understanding what drives Muslim sentiment.

The Rebirth of Propaganda

When Americans picked up The New York Times on April 20, 2008, many were shocked by a front-page story outlining the Pentagon’s practice of surreptitiously placing administration-vetted military analysts on major media networks to espouse administration war policy. The idea of covert propaganda, right here on American soil, seemed implausible. It was something that just didn’t happen in America. But propaganda works best when imperceptible: when it becomes ubiquitous, a part of the scenery and as commonplace as an American flag lapel pin.

The analyst story highlights a rebirth of propaganda as a foreign policy tool and sadly, the resumption of a failed strategy that has undermined U.S. Mideast diplomacy since the end of World War II.

Following the tragedy of 9/11, the U.S. experienced a revival of public diplomacy in the Middle East on a scale not seen since the Cold War. The October 2001 appointment of Charlotte Beers, the former head of the J. Walter Thompson and Ogilvy & Mather advertising agencies, as undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy and Public Affairs signaled that the country was preparing for an aggressive and sophisticated propaganda effort designed to both sell future military activity to Americans (i.e., the invasion of Iraq) and influence sentiment in the Islamic world. Beers’ appointment was followed up a year later with the establishment of the Office of Global Communications and the re-activation of the Cold War-era Counter-Information Team.

Beers’ team quickly got to work. By 2003, retired Air Force Colonel and administration critic Sam Gardiner was able to document more than 50 media stories of questionable origin that included misleading or patently false information in the months leading up to and immediately preceding the invasion of Iraq.

Separately, it was reported that State Department contractors were paying Iraqi newspapers to run pro-American content disguised as bonafide news reports from independent journalists and had been hiring Sunni scholars to promote the U.S. agenda in the region. But the tactic was nothing new. In 1953, just three months after the democratically elected prime minister of Iran, Mohammed Mossadeq, was ousted in a CIA-backed coup after he attempted to nationalize the country’s oil industry, a foreign-service officer in Tehran wrote in a briefing to his superiors: “After some thought on the subject, the embassy believes it would be extremely useful for a publication well-known in Iran to carry either an editorial or an article which would cover the points mentioned above and which can be utilized to very good effect in Iran.”

The embassy determined that the publications with the most influence in the country were The New York Times, Newsweek and Time, and included a draft of an article titled “Dilemma In Iran.” The piece denigrated Mossadeq and his government, and supported a resolution to the Iranian oil question that was decidedly pro-Western.

This was business as usual for many in the media during the Cold War, and many outlets were actively engaged in intelligence work. This included everything from reporters publishing pro-American position pieces to newspapers providing cover for agency operatives. Sources report there were more than 400 American journalists who secretly carried out assignments for the CIA and U.S. foreign services during this period.

Journalist Carl Bernstein has detailed extensively the Cold War cooperation between the CIA and U.S. media outlets, including The Washington Post, Newsweek, The New York Times and the Louisville Courier-Journal (his 25,000-word article, “The CIA and the Media,” appeared as the cover story of the October 20, 1977 issue of Rolling Stone).

The Say-Do Gap in the Middle East

Recently declassified State Department documents confirm that the United States government maintained a sophisticated informational warfare program in the Middle East through most of the Cold War, with the most intense activity during the mid- to late-1950s. The program blossomed in 1953 with President Eisenhower’s creation of the United States Information Agency (USIA), which followed wartime precursors such as the U.S. Foreign Information Service, the International Visitor Program, the Office of War Information, Voice of America (which broadcast its first program to occupied Europe in Feb. 1942), and later the Office of International Cultural Affairs. (With the exception of VOA, all of the USIA was reintegrated into the State Department on October 1, 1999, and operates today as the Bureau of International Information Programs.)

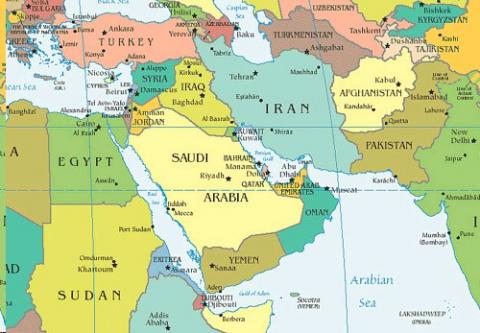

The symbols that were considered useful for propaganda in the Middle East (including countries like Egypt, Iran, Iraq and Syria) were intended to reflect well on American society and encourage a belief in shared Western-Muslim values. The idea was to present the notion that the United States, as the global representative of freedom and equality, could set the example of a democratic society around the world and provide a model for others to follow.

Yet the reality to anyone with access to a radio or newspaper was quite different from that which the American propagandists presented. As the USIA labored throughout the 1950s and 1960s to paint a picture of the United States as a freedom-loving democracy where equality reigned, concurrently its government supported the dictators and tyrants who were terrorizing the very populations to whom they preached their mantras. Meanwhile, at home, the realities of racial segregation offered a conflicting image to those around the globe who were being schooled on the virtues of American democracy while at the same time watching Black Americans being clubbed by police in the streets of America’s cities.

Policy vs. Propaganda – A Conflict of Goals

U.S. news manipulation in the Middle East throughout the 1970s was intended to change the way reality was perceived; in particular, the program intended to shift attention away from the Palestinian issue, in which the U.S. maintained a controversial position, and focus instead on internal problems of the host country (as long as they did not reflect poorly on governments allied with the United States), as well as point out how those problems could be overcome by further cooperation with the U.S.

Yet a fundamental misunderstanding of Arab culture, its politics, and the hopes and fears of its people virtually ensured that American overtures in the Mideast would be met with distrust, if not outright antagonism. While the U.S. worked tirelessly throughout the Cold War to counter Soviet influence and therefore emphasize anti-communism, it overlooked the real issues of the region, notably the plight of the Palestinians and the sufferings of much of the Arab populace under unpopular, dictatorial regimes (many of them with either tacit or overt support from the U.S and/or Britain).

“British and American propaganda in the Middle East failed because despite the technical competence with which it was conducted, it was not capable of affecting any significant change in the political climate in which it was forced to operate without substantial shifts in western policy towards Arab Nationalism and the Arab-Israel dispute,” writes historian James Vaughn, who has written extensively on the failure of Cold War propaganda in the Mideast. “In essence, the British and Americans wholly misunderstood their Middle Eastern audiences, who cared far less about the threat of Soviet communism than about Israel and their own fight for freedom from Western domination. Western propagandists were consistently striking at the wrong targets and found it impossible to effect any significant change in Arabs’ views … Policy and propaganda were out of sync.”

For the front-line Foreign Service officers charged with implementing American policy around the globe, this is no earth-shattering revelation. Throughout the Cold War, U.S. propagandists in the Arab Middle East repeatedly pointed out that their work would come to naught without a compliment of policy initiatives that reflected the message they were being asked to present. Time and again they warned that in the absence of an effective policy approach, their most ingenious techniques would be of little use. And time and again they were largely ignored.

Their frustration is nicely summed up by U.S. Baghdad public affairs officer Armin Meyer, who, writing to his superiors in Washington in 1948, expressed concerns that are equally relevant today: “With special reference to the Middle East, it is evident that the value of the information program is dependent upon basic American policy. We are judged by our actions in the political field, notably the Palestine issue; by our conduct in economic matters, notably oil; and by our efforts in the social sphere in assisting the alleviation of misery attendant upon which such abject poverty as abounds in this area” (as cited by James Vaughn in “Cloak Without Dagger: How the Information Research Department Fought Britain’s Cold War in the Middle East, 1948-1956,” Cold War History, 2004).

Unfortunately, U.S. policymakers today seem content to follow the same disastrous path they have for more than half a century. Until the implementation of fundamental changes in U.S. policy in the Middle East — including a draw-down of militarization in the region and, even more importantly, support for a comprehensive and unbiased resolution to the issue of Israeli-Palestinian conflict —America’s rhetoric of freedom, equality and democracy will continue to fall on deaf ears.

Author Bio:

Writer and photographer Christopher Moraff (www.christophermoraff.com ) is a news features correspondent for The Philadelphia Tribune and a contributing writer for the magazines Design Bureau and In These Times, where he serves on the Board of Editors.