Racial Dynamics and Latin Music in the U.S.

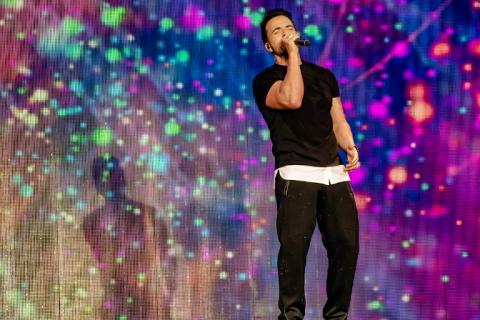

When it was first released on January 13, the song Despacito was available only as a digital download. It was the first single from Puerto Rican singer Luis Fonsi’s upcoming ninth studio album, and it featured fellow Puerto Rican reggaeton artist Daddy Yankee. Less than a month later, on February 4, it debuted on Billboard’s Hot Latin Songs chart at number 2 and at number 88 on the coveted Billboard Hot 100. In just about two months, the single would climb the Hot 100 chart to peak at number 44, while it crowned the Hot Latin chart at number 1 for, at the time of writing, 34 weeks.

On April 17, a remix version featuring the vocals of Canadian pop singer Justin Bieber was released. A month later, the remixed single reached the top spot on the Hot 100, where it would remain for a historic 16 weeks, the most weeks at No. 1 ever in the 59-year history of the Billboard chart, sharing the spot with Mariah Carey and Boyz II Men's "One Sweet Day," which set the record in 1996, unmatched until now.

There are many reasons why Despacito is such a massive success – harmonically and lyrically, the song is a textbook pop song. But the fact remains that a mostly-Spanish song has broken a long-held record in the American music industry, and that it was a momentous event in Donald Trump’s America is not lost on many.

There have now been only three mostly-Spanish songs to hold the No. 1 spot on the Hot 100 chart. The first was Ritchie Valens’s La Bamba in 1987, followed by the Macarena in 1996 during the dance craze of the 90s, a catchy tune by Spanish duo Los del Río. That only three Spanish songs have hit the top spot in a country with nearly 57 million Latin-Americans (that’s more than the entire population of Central America) is telling in and of itself, but perhaps even more so is the fact that these milestones did not occur without a nudge by the English language.

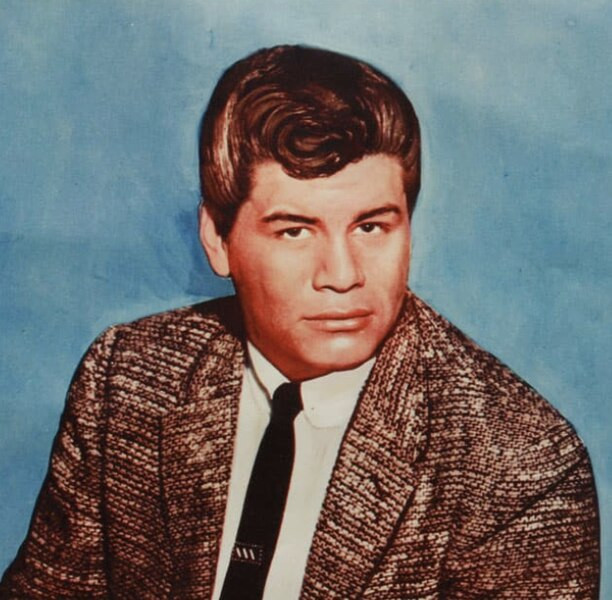

While La Bamba remains the only all-Spanish-language song to hit No. 1, it is not in its original iteration. La Bamba is a traditional Mexican folklore song, originally from Veracruz, best known by Ritchie Valens’s 1958 adaptation. The song gained wide popularity and entered the Top 40 chart just 2 weeks before 17-year-old Valens, who was of Mexican descent, was killed in the same plane crash that took the lives of Buddy Holly and JP “The Big Bopper” Richardson in 1959, a date famously dubbed “the day the music died” by songwriter Don McLean.

Rolling Stone magazine ranked Valens’s version of the song at number 354 on its list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time; it is the only song on the list sung in a language other than English. But it wasn’t until 1987 when the rock band Los Lobos recorded a version of Valens’s song for the soundtrack of the movie of the same name (starring Lou Diamond Phillips), that the song finally hit No. 1, becoming the first Spanish song to reach the spot, where it spent three weeks. Interestingly, Valens, who was born in California and was still a high school student when the song was released, did not speak Spanish.

Meanwhile, Los del Río’s Macarena did not even place on the Hot 100 chart when it was originally released back in 1993 as a rumba. A second version of the same song, also released by Los del Río that featured a more flamenco-driven rhythm, was a significant success in many Spanish-speaking countries, including Los del Río’s native Spain, Mexico, and Colombia. The song was also a huge success in Puerto Rico, where it was being used as the unofficial campaign song by governor Pedro Roselló while seeking reelection (in a remarkable resemblance to the infamous 1996 Democratic National Convention).

Many attribute the spread of the song to American cities with large Hispanic populations, such as Miami and New York City, to the fact that Puerto Rico was a popular destination for cruise ships, where visitors were constantly exposed to the catchy tune. Years later, in 1995, the Bayside Boys released a remixed version of the song with only a passing resemblance to the original. This version added a more techno dance beat, sanitized the story of the sly, loose woman named Macarena referenced in the song, and added English lyrics. The remix was created unofficially when two Miami DJs commissioned it, and it was only after it started to gain popularity that RCA bought the rights to the song, launching it to global recognition.

In 1996, three years after its original release, the English remix of the Macarena went on to spend a noteworthy run of 14 weeks at No. 1 on the Hot 100 chart. In a striking similarity with Despacito, it debuted at number 45 when it was first released. The song actually fell off the chart at the beginning of the year, and it was only after WKTU New York added it to its pop roster that the song finally reach the top spot in May of 1996.

On its part, Despacito was poised to be an international hit from its inception. Melodically, the song borrows from a number of tried-and-true cadences. Most notably, it features the clave as its basic layer, a remarkably old beat that traces back generations and can be found in various musical melodies, including the ring shouts—one of the oldest African-American musical institutions—Cuban church choirs, and it was even the main element in the composition of Valens’s La Bamba.

More on the surface, the song features a heavy beat of what most Puerto Ricans would call “dembow,” a rhythmic pattern deeply connected to the African diaspora that was made popular in the 80s by Jamaican producers. The term, in fact, is taken from Shabba Rank’s 1991 song “Dem Bow.” Meaning “they bow,” the song was an explicit anti-colonialism anthem heavily laced with anti-gay rhetoric. The rhythm is what would eventually become the basis for the origin and rise of reggaeton.

And perhaps most recognizable are the song infectious chord progression of vi-VI-I-V, an arrangement of the four chords most commonly used in popular music over the last century (this was humorously showcased in Axis of Awesome popular video “4 Chords”). These chords are what lend the song the romantic lift that Fonsi is known for. The song shares these chords with some of pop music’s biggest hits of the past 20 years, including Smashing Pumpkins’ “Disarm” (1993), the Cranberries’ “Zombie” (1994), Avril Lavigne’s “Complicated” (2002), OneRepublic’s “Apologize” (2006), Akon’s “Beautiful” (2008), Lady Gaga’s “Poker Face” (2008), Eminem’s “Not Afraid” and “Love the Way You Lie” (2010), and Tiësto’s “Red Lights” (2013), among many others.

In other words, Despacito was composed to be a Latin smash hit, in addition to the fact that it was performed by two of Latin America’s biggest stars. Daddy Yankee had been in the industry since the 1990s, when Reggaeton was still an “underground” genre circulating around Puerto Rico. He was a popular performer even before his smash hit “Gasolina” hit the airwaves in 2004, launching him to international stardom and scoring his first spot in the Hot 100 chart, when Americans were first introduced to the artist. Fonsi, on his part, is currently working on the release of his ninth studio album. No less than 30 of his singles have charted on Billboard’s Hot Latin Songs since he first rose to fame in 1998.

Many speculate that it is this pop-driven beat that Fonsi is known for that created the perfect environment for Justin Bieber to collaborate. Even though a version of the dembow sound is sampled in his hit “Sorry,” the cuatro that features prominently in Despacito is ideal for Bieber’s soft, buttery vocals that harmonize seamlessly with Fonsi’s crisp voice.

According to Fonsi, Bieber heard the song in a club in Bogota while touring in Colombia. He immediately called his producers and arranged for the remix of the song, which was recorded four days before it was released. While the song remains widely unchanged, Bieber opens the tune with an English verse before resorting to singing in English alongside Fonsi during the contagious chorus. Fonsi attributes this collaboration to the spread of the song’s popularity in the American music mainstream, introducing it to a wider audience who would have otherwise stuck to the conventional pop songs saturating the airwaves.

It is interesting to note that even though this was the first time that Bieber recorded in Spanish, other major artists have certainly tried before. Current hit-maker and fellow Canadian Drake, for example, collaborated with the immensely popular Dominican-American bachata singer Romeo Santos, where Drake sings in Spanish. Nicki Minaj and Usher did similar collaborations with Santos, who is a fully bilingual artist born in New York City and who has famously refused to accommodate English-speaking American artists when they wish to collaborate on his tracks.

What sets Despacito apart, certainly in political terms, is the presence of the reggaeton dembow beat that percolates through the song. As mentioned above, the beat and its EDM cousin “moombathon” have been prominently borrowed in other genres; in addition to Bieber’s latest hits, Ed Sheeran’s “Shape of You” could be easily confused with dancehall reggae, and Ariana Grande’s “Side to Side” is built on top of that thump-tha-THUMP-thump beat that powers Despacito.

But historically, reggaeton has been a genre of music deeply immersed in the racial dynamics of Central America – particularly in Panama, where the genre “reggae en español” first saw the light, and Puerto Rico, where it was fully developed into reggaeton and is generally considered its place of origin.

Much like American Hip-Hop, reggaeton was first an “underground” genre that came from urban, predominantly black, working-class communities. In the Puerto Rican context, reggaeton’s emergence in the 1990s is tied to public housing developments that were part of anti-crime initiatives in the island. Dubbed Mano Dura contra el Crimen (Iron Fist against Crime), it was enacted in 1993 by then governor Pedro Roselló (the very same one who danced to the Macarena in his campaign rallies). With uncanny resemblance to President Clinton’s 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, the Mano Dura imposed tougher sentences on petty crimes and funded more weaponry and larger ranks of the police departments. And like America’s controversial Crime Bill, it disproportionally targeted black and indigenous individuals. In this tense political climate, reggaeton flourished.

Now widely known for its misogynistic and sexually explicit lyrics and undoubtedly tied to perreo (derived from the word “dog” in Spanish, this is the lewd sexual dance moves it involves), a reggaeton-laced song is now the No. 1 in America. Though this is perhaps not so surprising. After all, Latin-Americans are the second fastest-growing minority in the U.S. (Asians are the first). What is surprising is that Despacito is only the third mostly-Spanish song to top the American charts, even though the overall number of Latino, African-American, and Asian students in public K-12 schools now surpass the number of non-Hispanic whites. And while Latin representation on the charts should be celebrated, a reggaeton-pop fusion song claiming the No. 1 spot may feel like a good antidote to the current divisiveness on immigration reform and to the increased ICE raids and deportations, but its success also serves to underscore the hurdles the genre still faces.

Despacito can also claim to be the most-streamed song of all time, and its music video the most-viewed video on YouTube in the world. Despite these milestones, the music video failed to claim a single MTV Music Video Award nomination in any of the categories, a decision that garnered much backlash and that MTV explained as a simple misunderstanding. MTV eventually bequeathed the song—the remix version of it featuring Justin Bieber—with a nomination on the “Song of Summer” category, which was announced almost a month later. It lost.

Author Bio:

Angelo Franco is the chief features writer for Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine

Photo Credits: Depositphotos.com; Wikipedia.org; Pete Souza, WhiteHouse.gov (Wikimedia.org, Creative Commons)