Photographer Nan Goldin and a Long-Lost Era of New York Subculture

Susan Sontag in On Photography, her iconic look at the camera’s impact on society, stated that “to photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed.” In other words, once you click on a chosen subject, it belongs to you forever. Nancy “Nan” Goldin, whose images taken between 1979 and 1986 of the hard-core subculture of her Bowery neighborhood, as well as forays in Berlin and Boston, has created her own 35mm record of permanency. These lovers, friends, and strangers, most of whom became casualties of their time through drug overdoses or AIDS, are sadly, long gone. But their snapshots remain to comfort and perhaps haunt their owner.

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a title taken from a song in Bertolt Brecht’s Threepenny Opera, is Goldin’s most famous work. Comprising almost 700 photographs, painstakingly assembled with a little help from her “tribe” into a 42 minute film—peppered with lyrics of her choice throughout—is the mainstay of The Museum of Modern Art’s current exhibition. As Goldin confesses, “It’s the diary I let people read. The diary is my form of control over my life….to obsessively record every detail. It enables me to remember.”

Such nakedness of purpose is rare in an artist. It’s a work that begs us to pay attention and if only for that reason alone, MOMA is to be commended for bringing it once again to the forefront of our consciousness. An early mockup of the book, published by Aperture in 1986 with a book design by Keith Davis, is on display along with various posters and silver dye bleach prints adjacent to the screening room. Ballad was originally presented as part of the Whitney Biennial in 1985 and subsequently at the Berlin Film Festival in 1986.

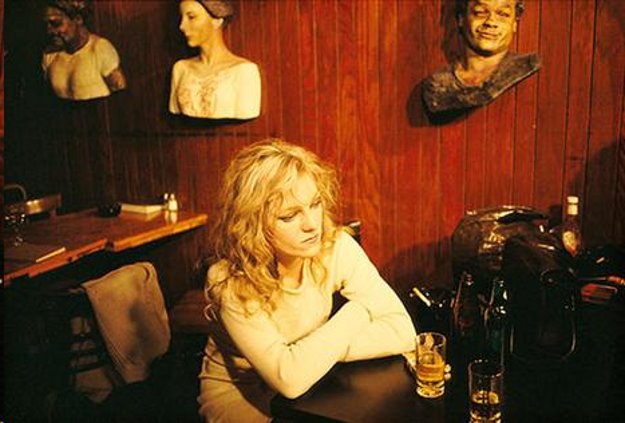

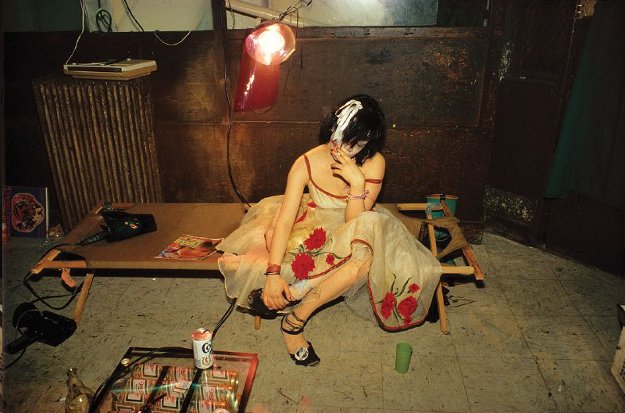

Surrendering in the dark to this cast of characters—in and out of bed at pre-coital and post-coital moments—feels at times clandestine, like having wandered unwittingly into a peep show. Faces and bodies appear on the toilet, in the tub, lolling in doorways, supine on sofas, hanging off the trunks of convertibles. They smoke, drink, shoot up, pose, celebrate over birthday cakes, bare their breasts and buttocks. Transvestites, body builders, even a young woman in her trimester of pregnancy, confront the viewer with the blank-eyed stares of the downtrodden. There’s not a lot of daylight in Goldin’s world. We sense entropy, that whatever pleasures were given or stolen are over too soon. What is left are empty rooms, rumpled sheets, a bloody wall without explanation, and the isolation that follows.

One can’t blame the viewer for being grateful for the occasional image of domesticity, of familiarity between subjects that may in some instances pass for love. An elderly couple dancing awkwardly with one another, an affectionate hug whatever its impulse, is a welcome interruption sandwiched between so many other images of degradation and desperation. Such obsessions in a photographer are not easy to quiet, and the trove of pictures from that period led to two other series: I'll Be Your Mirror (from a song on The Velvet Underground's The Velvet Underground & Nico album) and All By Myself.

It’s impossible to confront such an exhibit and not wonder about the how’s and why’s that led to little Alice’s fall down the rabbit hole. Clearly, the early trauma of losing a big sister to suicide when Goldin was only 11 had to leave a spiritual vacuum. It was at the Satya Community School outside of Boston that a teacher, sensing a nascent curiosity in her pupil, introduced her to her first camera. In an image-driven culture, early influences were easy to adopt—Andy Warhol, Federico Fellini, Helmut Newton were hers for the taking. By 18, having graduated from the Museum of Fine Arts at Tufts University, she found herself in the hub of New York City’s post-Stonewall drug culture. A colorful bevy of drag queens were all too ready to serve as mentors for her camera’s eye. “I really admire people who can recreate themselves and market their fantasies publicly.”

It’s easy to see how the camera became the natural answer for exposure of others as well as self. For Goldin, the line between art and life soon became so blurred as to be almost nonexistent. Among the most riveting photographs greeting the viewer in the first room is 'Nan One Month After Being Battered, 1984'. Hard to look at, it’s a brave, iconic image which undoubtedly served her own needs at the time. For others, it can be read as an unsparing cry for help.

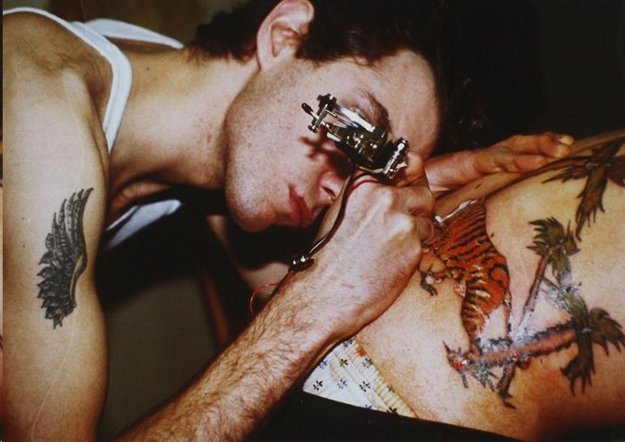

In the same display, there are other arresting images to catch the eye. The Hug, NYC, 1980, features a woman adorned with a long wig with back to the camera. A muscled arm clutches her around the waist, the only body part we see of the male. In Mark tattooing Mark, we see a close up of a man tattooing a tiger and palm trees on his stomach. Another image that stands out, mainly because it’s the only landscape in the show that seems to define itself as such, is Sun Hits the Road, Shandaken, NY 1983. There’s a melancholy in the picture, perhaps because the road acts as its only subject.

It’s easy to see Goldin as the heir apparent to Diane Arbus. Both precocious, both raised by Jewish parents preoccupied with their own successes or obsessions, as young women they were, more often than not, left to their own devices. Free to seek outlets to a world beyond the narrow scope of their upbringing, they chose a descent into a netherworld. Whether through an insatiable curiosity in Arbus’ case or an obsessive dependency in Goldin’s, it was a dangerous journey. Arbus’ genius was not enough to save her, and she committed suicide in 1971 at 48. Goldin continues her own search today and at 63, it may be doubtful she will ever fill the void that the early suicide of her own sister left behind. But the work since 1995 is more varied in subject matter, more mature. Since 1995 she has embraced a wide array of subject matter, everything from collaborative book projects with Japanese photographer Nobuyoshi Araki, to urban skylines, and not surprisingly—family life.

In an age of “selfies,” an impatience to seek out Facebook fame—not within the parameters of Andy Warhol’s 15 minutes but better yet, 15 seconds—Nan Goldin’s pictures give us pause. An image can have the power to shake our souls, to realize what is saved and what is lost.

The installation is organized by Klaus Biesenbach, Chief Curator at Large, MoMA, and Director, MoMA PS1; Rajendra Roy, The Celeste Bartos Chief Curator of Film, MoMA; and Lucy Gallun, Assistant Curator, Department of Photography, MoMA. The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is on view through April 16, 2017.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief arts critic.

For Highbrow Magazine