The Brash New World of Trenton Doyle Hancock

If you think paying a visit to your local museum exhibit is a relatively safe endeavor, then beware. It’s likely you have not visited the The Studio Museum of Harlem’s current exhibit, Trenton Doyle Hancock: Skin and Bones, 20 Years of Drawing. Chronicling the evolution of his comical, often nightmarish universe, it’s a show that may alternately delight and repel but guaranteed, one you will not soon forget.

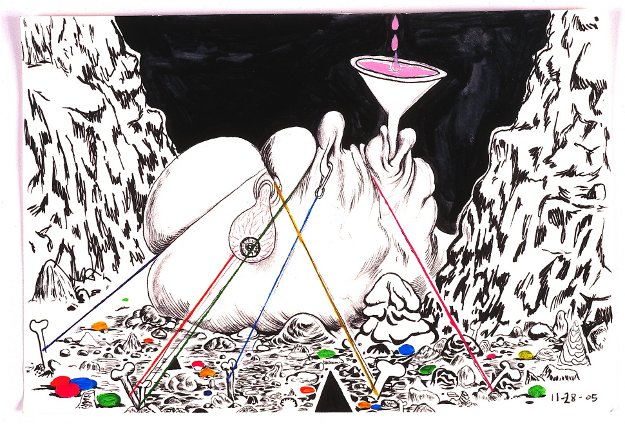

When you first gaze upon a signature head from Hancocks interior world (…And Then It All Came Back to Me, 2011), you will find a striped, furry face with bulging, bloodshot eyes unlike any you’ve seen before. Once over the initial shock, it’s evident that its creator is a seasoned artist—a deft illustrator of the fabulous whose way around a curve, the tonality and contrasts of form exhibit extraordinary delicacy and skill. But that’s only the beginning.

The creature encountered is likely an inhabitant from an epic narrative, 10 years in the making, stretching across the main walls of the museum. These are mythical personages that meet the eye, exemplifying the legend of the Mounds. It’s a civilization comprised of Mounds and Vegans, locked into an eternal battle between good and evil. Numerous beings scuttle back and forth, operating massive conveyer belts, where meat-eating Mounds are converted into tofu. (Yes, he does have a raucous sense of humor.) The Vegans are the culprits in this extravagant tale, half plant and half animal. Names are given to his hairy horde, like Homerbunctas, the father of the Mounds. A nod to Ulysses’ creator perhaps?

“Faith has brought us this far…” is just one of the many fragments of phrases that surround Hancock’s drawings and collages. A certain mysticism prevails in these outpourings, such as “a painter is a spirit energy who brings color to the world.” Moving from one grouping to another around the room—whether encountering early editorial cartoons from his college days at Texas A&M University in the glass vitrines on display, or a graphite paper sketch of a golf game, depicting The Desecration of the Gopher’s Home, the eye is drawn back to these accompanying scrawls that cover the walls.

In an interview with Lauren Haynes, the Associate Curator of the museum’s permanent collection, Hancock calls this narrative his “visual bridges.” His aim is “to create fields of wall-drawn information that extend the boundaries of the framed works. This arises “from the desire to create an environment or context for the works.” For over 12 years, he has been producing wallpaper as a vehicle for narrative forms, icons and his own looping vignettes.

The viewer may take these musings as clues to the mystery of the works themselves or they may simply give rise to more questions. No easy answers are to be found here. The same could be said of the works of the 15th century’s Hieronymus Bosch—his Garden of Earthly Delights brought several generations’ idea of hell into sharp focus. Hancock’s early roots were based on his comic superheroes. As he matured, his faith dwindled in such fictional characters as mentors. He was drawn instead to the confessional comics of Robert Crumb, another controversial cartoonist who came to prominence with the 1968 debut of Zap Comix and his counter culture mischief-maker Fritz the Cat.

If cartoons function as a rich medium of expression for him, he is above all, a socio-political commentator of his times. He has alluded to the 19th century Belgian painter James Ensor and the 20th century German expressionist Otto Dix as favorites. Both of those artists were proponents of searing satirical takes on the dangers of conformity.

In an adjacent room, a character dubbed “Torpedo Boy” functions as the artist’s alter-ego. Through a series of panels, and accompanying text, we discover that he has stolen food. This pictorial journey also includes an ugly brush with a prostitute. With their pornographic underpinnings, these images are bound to offend some viewers, and a Parental Guidance warning would not be unwarranted if a planned family outing includes this exhibit. It’s worth noting that a number of paintings and photographs that are part of the permanent collection are also on view.

When Ms. Haynes broached the subject of Hancock’s upbringing in Waco, Texas, and his home base of Houston, his response to its influence could hold a clue to such “in your face” works. “There is a lot to celebrate…but also there’s plenty of negativity and strangeness to react against.” Addressing the wide-open sprawl of the state, he confessed that it has “allowed me the space to nurture not only my collecting habits but also my anger.”

Transforming at least some of that anger into art has paid off for this artist on the fringe. Hancock received a commission for an Austin Ballet production, “Cult of Color,” which gave him the opportunity to see his characters moving about the stage. That exposure allowed him to consider a translation into animation for his works. In 2007 he was the recipient of The Studio Museum’s Joyce Alexander Wein Artist Prize. Yet another progression has been delving into toy production for his stable of characters.

The current show has enjoyed an auspicious beginning. The Contemporary Arts Museum Houston (CAMH) was the first home for this ambitious undertaking, curated by Valerie Cassel Oliver, followed by an installation at the Akron Art Museum. This is its third incarnation, where it will remain through the end of June.

Since the attack on the Charlie Hebdo editorial staff earlier this year, the power and consequences of a free press to satirize through image and text has never been more in the forefront of the news. And even museums have come under pressure from time to time from their own boards when a show is considered too incendiary for public consumption. Hancock has a unique vision and sensibility that deserves to be seen. And the Studio Museum of Harlem can be congratulated for highlighting such an edgy and important artist.

Author Bio:

Sandra Bertrand is Highbrow Magazine’s chief art critic.