The Temptation of the Intellectuals: LBJ and the 1965 Festival of the Arts

It is a bright early Summer`s day in the White House`s Rose Garden. Two men - the film-star, Charlton Heston and the highbrow cultural critic, Dwight Macdonald - stand fiercely arguing about whether it is right for guests to a Presidential event - in this case the Festival of the Arts held 50 years ago in June 1965 - to disturb proceedings. Although etiquette is the ostensible subject of the quarrel, tempers are running high because simmering beneath the surface is the heated issue of the Vietnam War.

The Festival takes place at a critical and turbulent time in modern American history. In a society increasingly marked by division and conflict, due initially to the struggle for Civil Rights and then to the slowly gathering campaign to stop the War, the US Administration is keen to ensure that alternative voices to the those on the radical Left can be heard. For although Lyndon Johnson, from taking office in 1963, has been a reforming president, introducing large-scale social programs to alleviate poverty, end racial discrimination and improve educational opportunity, he is in danger, as a result of his military interventions in Vietnam and the Dominican Republic, of losing the support of a significant segment of the nation’s liberal intelligentsia

Intellectuals have often given governments a hard time. From Jonathan Swift to Harold Pinter, they have served as the proverbial thorn in the flesh of the powerful. Yet, political leaders have also not been slow to recognise the potential value of art and artists to their cause, especially at times of crisis. Going back a hundred years to 1914-18, the British government, for example, was quick to co-opt several leading authors to write in support of the country`s war effort and recent revelations indicate that the CIA was keen to use the arts, including Abstract Expressionism, to promote Western values and interests during the Cold War of the 1950s.

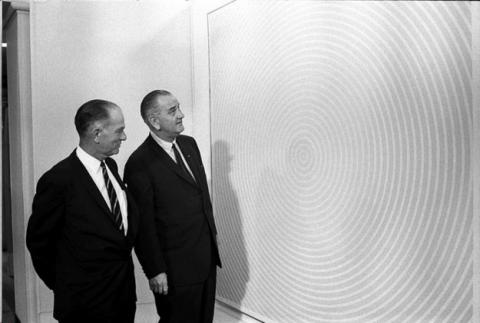

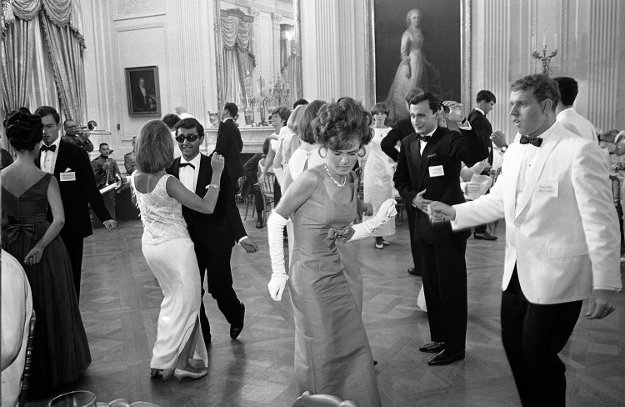

The 1965 White House Festival of the Arts, held on Monday June 14th, is also designed with a political agenda in mind, in this case to win over America`s cultural elite. The occasion would support community arts certainly, it would help most probably counter the President`s image, in contrast to that of his predecessor, JFK, as a rough-cut Southerner with little interest in music, art and books, and most importantly it would recruit potential influential opponents or doubters of his foreign policy to his cause. As the decision to escalate the War by systematic bombing gets closer and as student hostility to the War gathers pace, so the attraction of having at least some of the nation`s intellectuals on side grows. If the Government cannot count on the support of America’s students, then perhaps it can rely on the backing - implicit or explicit - of a few well-respected writers or artists.

So, with the First Lady`s enthusiastic support, preparations begin. Letters are sent, phone-calls made, art-works requested and schedules drawn-up. Many want to be invited, leading chief-organizer, Eric Goldman, to say, `I never experienced anything like the assault for an invitation to this event.’ And whilst there are obstacles - an in-demand female actor for a performance of a scene from Arthur Miller`s Death of a Salesman can`t immediately be found, museum directors need persuading to loan paintings and questions are raised about the absence of Indian art - everything seems to be going relatively smoothly until a letter, addressed to the President, arrives.

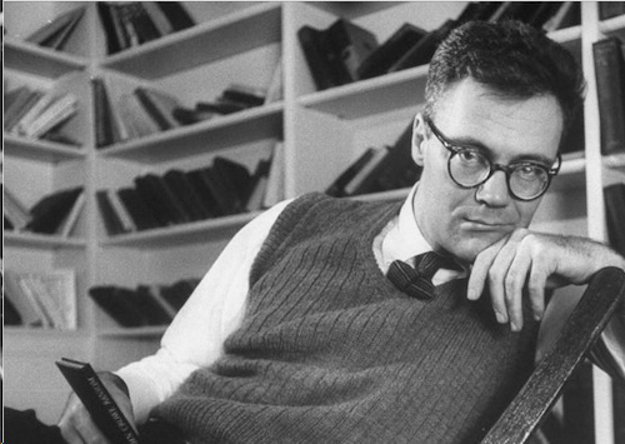

Robert Lowell is certainly a well-known public figure in 1965, having published both Life Studies and For the Union Dead, two of the century`s most important collections of poetry, and had already been ‘outraged’ by the US’ nuclear policy and its interventions in far-off countries. Perhaps then, the surprising thing is that he should have initially agreed to a poetry reading on the 14th June rather than the fact that a few days after accepting, having listened to the opinion of his friends, including Philip Roth, he should join Edmund Wilson and E. B White - two other prominent writers of the time - and change his mind.

The carefully-chosen words of Lowell`s letter, with their reference to his uncertainties and indecision, express not so much his anger at the War but his anxious sense of the dangers of this `anguished, delicate’ moment - `We are in danger of becoming an explosive and suddenly chauvinistic nation, and may even be drifting on our way to the last nuclear ruin’- and his difficulties as a `private and irresolute man’ to make a public stand. And it is these difficulties that make the poet’s hard-won decision to absent himself - a decision he sticks to in spite of Goldman’s lengthy attempts to change his mind - the more telling. How much more powerful is his conflicted and reluctant refusal to sup at the President’s table - a refusal soon to be published on the front page of the New York Times - than the slogans and polemics of other opponents of the War.

If Lowell represents one response of the artist to the temptations of official favors and flattery from above, his contemporaries make different choices. Saul Bellow, for example, accepts his invitation in spite of his hostility to US military interventions, arguing that the Festival should not be regarded as a political occasion; by accepting ,Bellow believes he is merely honouring the president’s office, not supporting his foreign policy.

John Hersey, best known for his non-fiction book, Hiroshima, also agrees to attend the Festival but will not, in spite of considerable pressure from organizers, particularly from Mrs Johnson - `The President and I do not want this man to read these passages in the White House’ - succumb to the demands to read only from his novels. For Hersey, the event is an opportunity to gain Johnson’s attention and confront him with the horrific human costs of modern warfare and, as with Lowell, to emphasise the dangers of escalation - `Let these words be a reminder,’ he prefaces his reading, `the step from one degree of violence to the next is imperceptibly taken and cannot easily be taken back. The end point of these little steps is horror and oblivion.’

Unable to spot the President in the audience - LBJ had decided, as an expression of his anger at the way the Festival is unfolding, to only attend the reception - Hersey directs his readings at his wife, sitting stony-faced in the front-row. Selecting two passages from his book - one about the suffering produced by the bomb and one that presents, in cold statistics, the terrifying potential of nuclear weapons - he succeeds in graphically bringing home to his cultured listeners, modern warfare`s brutal effects on human beings in a far off land. If ever there was an example of speaking truth to power, then surely this is it.

Another guest who is strongly opposed to Johnson’s policy in Vietnam is Dwight Macdonald - a well-respected writer on culture and society. Invited to the Festival just before he, along with several well-known artists and writers, had put his name to a telegram expressing support for Lowell’s stand -` We would like you to know that others of us share his dismay at recent American foreign policy decisions ‘- MacDonald thinks about following the poet’s example, only deciding to attend the Festival when friends suggested how he might turn his attendance into a form of activism.

Writing about the occasion is one option but organizing a petition in favour of Lowell’s position amongst fellow guests, strikes Macdonald as a potentially more effective move. As with Hersey, here is a chance, he sees, to campaign against the War in the very place from which it is being waged - the White House. So, when accused by Charlton Heston of lacking `elementary manners’ , Macdonald stands firm; for him the issue of Vietnam trumps the issue of etiquette. Embarrassment and Presidential rage - LBJ denounces his critics as `sonsofbitches` - are the necessary price to be paid for taking a stand.

Not everyone, however, is so steadfast in the face of pressure - however charming and light-touch is this pressure. Chair of the Festival, the literary scholar, Mark van Doren, redrafts his speech, after a lengthy conversation with Goldman, to play down favourable reference to Lowell’s decision to stay away and to play up his praise for President Johnson’s hospitality to members of the art world. Reassured that he could say whatever he likes, he says what Goldman likes, providing a clear reminder of the soft-power exercised by the well-meaning servants of liberal democracies.

Arguably, it is the strength and reach of this soft-power that is at stake in the case of the 1965 Festival of the Arts. Flattered to receive an invitation to the occasion from the White House, only five out of the 102 people who are asked, choose to say no on political grounds, for the temptation to accept the warm embrace of authority, whether in the form of invitations or honors or prestigious roles was not easy to resist fifty years ago and is not easy to resist now. An argument can always be made that it is better for everyone, not least yourself, to stay on side and silent.

Yet, in retrospect, who can say that Robert Lowell, by refusing to attend the Festival on June 14th, and John Hersey and Dwight Macdonald by attending but not following the rules, were mistaken? Here, were three intellectuals and artists who, in their different ways, believed that they had a responsibility to leave their respective studies to take the fight to their political masters. Saul Bellow, and others, may have thought it right to draw fine distinctions between the President as institution and the President as policy-maker and risk committing Julian Benda’s `trahison des clercs’. However, for Lowell, Hersey and Macdonald the moral case for making a statement about the Vietnam War by their actions is too powerful. Sometimes, they would argue, intellectuals do have to bite the hand that feeds them.

Although President Johnson did not change his foreign policy as a result of the opposition from the world of the arts that he encountered on June 14th, the White House Festival of the Arts is nevertheless a significant moment, even looking back at it fifty years on. Afterwards, no one has any illusions about the huge gulf that had opened up in the culture between the politicians and America’s liberal intellectuals. Having failed engage in a proper dialogue with his critics, as Goldman wished for - a dialogue which might have created a pause for reflection and compromise - and angered and humiliated by the rebuffs he had received, Johnson believed there was now no alternative than to further escalate the War.

All critics of his policy became unpatriotic, required to answer the question of whether they are helping `the cause of the country’ and suspected of being Soviet tools. The idea of the Great Society, which had inspired the president and his followers falls by the wayside and almost all energies are focused on achieving a military victory. Thus, while still aware of voices advising caution and of the danger of public opinion turning against him, Johnson does nevertheless, in the days and weeks after the Festival, decide to use US B-52 aircraft to undertake saturation bombing of North Vietnam and to send an additional 100,000 troops to the battlefield. The time for looking at pictures, watching plays and listening to poets was over.

Author Bio:

Mike Peters is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.