Genius and Addiction: Creative Fuel or Speedway to Self-Destruction?

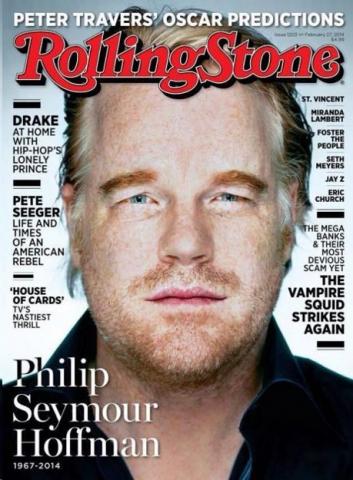

Philip Seymour Hoffman was one of the great actors of his generation, delivering superb and very memorable performances in films such as Boogie Nights, Scent of a Woman, Doubt, Almost Famous, The Big Lebowski and, of course, Capote, for which he won the Academy Award for Best Actor. Many fans of his work were shocked by his untimely death from a drug overdose in February of this year, the result of a relapse after a long run of sobriety. Hoffman was perhaps the most notable of celebrity drug-related deaths of this decade, but he was not the only one to lose his life to addiction. In the previous year, actress Lisa Robin Kelly (the original Laurie Forman on That ‘70s Show), Glee’s Corey Monteith and rapper Chris Kelly, from the 1990s duo Kris Kross, all lost their lives prematurely to their struggles with drugs and addiction.

We are all well familiar with the many stories of celebrities who have met similar ends, a list which could well take up the length of this article. And then there are also those many people, whose names do not top Web search results lists and whose faces do not land on the covers of popular publications following their deaths from drug abuse, everyday men and women who battle the demons of addiction off and on throughout their lives.

Far from moralizing – as many media articles tend to do – or for that matter endorsing drug use, the purpose of this article is to present substance use in a dichotomistic fashion, as something that can both add fuel to the bright fire that is genius and can also hasten one’s physical decline and even death. Let’s look at a few prominent cases for illustration, starting with the more innocuous and moving on to the abusers of harder drugs.

Honoré de Balzac is often considered among the greatest novelists to have walked this earth. His La Comédie humaine is composed of nearly 100 works written over the course of 20 years. In addition, there were nearly 50 incomplete works at the time of his early death. The author often was working on several pieces at once and his manic creativity was driven by a dependence on coffee. And by a dependence, we are not talking about a mere pot of coffee, but upwards of 50 cups a day (depending on the source).

In his essay “The Pleasures and Pains of Coffee” Balzac writes, “Coffee is a great power in my life . . . . coffee sets the blood in motion and stimulates the muscles; it accelerates the digestive processes, chases away sleep, and gives us the capacity to engage a little longer in the exercise of our intellects.” In that piece he also elaborates on several methods of coffee consumption, ways of increasing the effect that coffee has on the senses, much as an addict of heroin might experiment with different ways of accelerating his high. Some argue that Balzac’s reliance on coffee contributed to his death of heart failure at the age of 51, following a string of headaches, muscle cramps, twitches and stomach problems, possibly the result of poor hydration of the body. But one also must ask, if coffee did not find its ‘victim’ in Balzac if we ever would have had the immense work of genius that has come to be known as The Human Comedy? For Balzac, excessive coffee consumption was inseparable from his artistic method.

While other artists, such as Beethoven, Bach, Voltaire and Proust, have shared Balzac’s affinity for coffee as an extractor of the mind’s creative juices, Balzac takes the cake. So legendary was his addiction that he even has a coffee chain in Canada named after him.

Today, despite the fact that in excess caffeine can have deleterious effects on one’s health, it is considered a relatively innocent drug. Another drug considered fairly harmless in society today, is alcohol, though we know that it can impinge our mental functioning, can increase risk of developing certain cancers and can cause a number of health problems that affect the working of important bodily organs like the kidneys and liver. We are well familiar with many of the famous alcoholics in recent history. Among the great poets, Arthur Rimbaud and Paul Verlaine attributed much of their hallucinatory imagery to their muse la fée verte. It was perhaps also the influence of this muse as jealous lover that caused Verlaine to shoot Rimbaud in the hand.

The Green Fairy also cast under her spell, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (who died at the age of 36 due to complications from alcoholism and syphilis, shortly after spending some time in a sanatorium), Van Gogh (who killed himself at the age of 37 and whose mental health problems may have been exacerbated by his alcoholism), Strindberg (who died of stomach cancer at the age of 63 – which may or may not have been due to his heavy drinking), Modigliani (who also had a fondness for hashish), Oscar Wilde and many others. While absinthe’s hallucinatory powers on the psyche are debatable, it certainly played a seminal role in the works of many great artists, and its negative effects led to regulations against its distribution and production in many parts of the world.

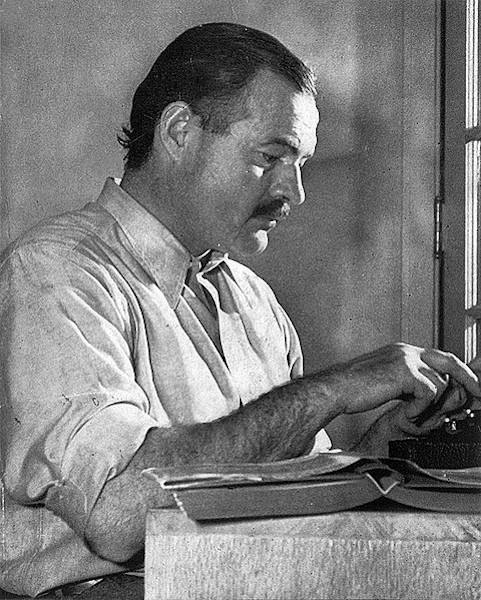

The list of famous alcoholics could be expanded on ad infinitum, or so it may seem. There was W.C. Fields (who died of an alcohol-related stomach hemorrhage), Hemingway (whose drinking caused him significant health problems in later life, before his suicide at the age of 61), Faulkner, Tennessee Williams (whose death at age 71 was drug and alcohol-related) and Dylan Thomas (who, as Nick Cave sings, “died drunk in St. Vincent’s hospital” at age 39). But let’s move on to another relatively harmless drug, tobacco.

Like alcohol, we know that tobacco can cause its fair share of health problems, such as emphysema and many types of cancer, and some studies have linked it to mental health issues like depression and dementia. And whereas the other drugs discussed so far (and to be discussed throughout this article) have no secondary health effects on those around the users, secondhand smoke from tobacco can have many poisonous effects on those who are exposed to it. For instance, habitual exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke as a child makes one more likely to develop lung cancer as an adult. Whereas for most drugs, the negative health effects are felt only by the users, tobacco users share toxins with all of those around them.

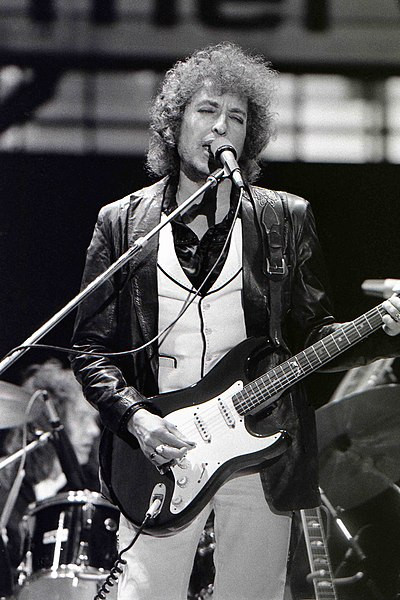

Many artists and thinkers we can hardly imagine without a cigarette or cigar in their mouths, including the likes of the comedian George Burns (though he drank moderately and smoked excessively he made it to the age of 100) and W.C. Fields, or Bob Dylan in the ‘60s. At the time that he was writing Eraserhead, a film that Stanley Kubrick has listed among his favorites, director and writer David Lynch claims to have drank upwards of 40 cups of coffee (Balzacian quantities) and smoked 40 cigarettes a day. The Band’s Levon Helm smoked as many as three packs of cigarettes a day, but died of throat cancer at the age of 71, 14 years after he was first diagnosed with the disease. Of course one of the past century’s most famous smokers was Sigmund Freud. It has been famously suggested that Freud once stated “Sometimes a cigar is only a cigar” (though there is no evidence supporting that Freud ever said this), to defend his cigar smoking against claims that smoking is oftentimes the result of a fixation on the oral stage of psychosexual development. Freud, it is reported, had a habit of smoking 12 to 20 cigars a day. It was not until the age of 67 that it was discovered that he had oral cancer, something which caused him intense pain and which would have led to his death if he had not been euthanized with morphine (16 years later) before the terminal illness had its way with him.

Not only was Freud addicted to tobacco, he was also a devotee of cocaine. Some have suggested that it was this reliance on cocaine that drove many of Freud’s perspicacious early ideas. Though Freud never used cocaine in mass quantities, it could be argued that it was for Freud’s creative activities what coffee was for Balzac’s.

Though his enthusiastic support of cocaine diminished over the years, Freud argued that cocaine could be the cure for many ailments, both mental and physical, points outlined in his 1884 essay “On Coca” and many subsequent articles. He also recommended cocaine as an effective cure for morphine addiction (sort of the modern equivalent of recommending methadone to heroin addicts). He stopped using the drug in 1896, before writing some of his most influential works, like The Interpretation of Dreams and Civilization and Its Discontents, though his reliance on tobacco continued.

Freud wasn’t the only coke-loving genius in the medical world. William Stewart Halsted, one of the founding professors of Johns Hopkins Hospital and one of the pioneers of modern surgery, was also a cocaine addict, as well as a regular morphine user. Like Freud, he used cocaine on himself in his tests of the then-popular anesthetic, and later switched from cocaine to morphine as a “cure” for his addiction to blow. Despite his genius and immense contributions to modern medicine, in his own day Halsted was known for missing work for long stretches, lying and making excuses, as documented in Dr. Gerald Imber’s biography of the innovative surgeon, Genius on the Edge.

While on the subject of famous opiate addicts, we shouldn’t fail to mention one of our nation’s beloved Founding Fathers, that brilliant inventor and thinker, Benjamin Franklin. Though Franklin was tremendously fond of alcohol throughout his life, like many of the Founding Fathers, his dependence on laudanum (a mixture of opium and alcohol) did not begin until later in life, starting with his use of it to treat medical conditions such as gout and kidney stones. Other famous laudanum users (and addicts) included literary greats like Edgar Allan Poe, Charles Dickens (whose heavy use of opium may have contributed to his death of a massive stroke at the age of 58) and Lewis Carroll.

While Benjamin Franklin is hardly best known for his alleged opiate addiction, any more than Philip Seymour Hoffman was until his death by overdose in February of this year, others better known for their opiate dependence are many.

In the world of music, famous opiate addicts included jazz greats like Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, Charlie Parker and John Coltrane (whose death of hepatitis at age 40 has been attributed by some to his heroin addiction), and rock stars like Sid Vicious, Aerosmith’s Steven Tyler (who claims to have spent upwards of $20 million on his drug habits) and Joe Perry, Janis Joplin (who died of a heroin overdose at the age of 27) and Kurt Cobain. Poets like John Keats, Percy Bysshe Shelley (whose opium addiction may have both helped his creative possibilities and hastened his mental decline) and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, it has been suggested, also had predilections to opiates.

Other opiate addicts include: writers like Louisa May Alcott and Williams Burroughs (whose 1953 classic Junky may be well-considered one of the best, objective literary accounts of the life of the heroin addict, the same as we might say of the Velvet Underground song “Heroin” in the world of music); and actors and comedians such as John Belushi (who died of a heroin and cocaine overdose at the age of 33), Chris Farley (who died of a morphine and cocaine overdose at the same age as his idol, Belushi), River Phoenix (who was only 23 when he died of an overdose from speedball use) and such classic stars of cinema as Peter Lorre and Bela Lugosi.

While the number of famous pill-poppers (Rush Limbaugh, William F. Buckley, Carrie Fisher, Elvis Presley), barbiturate users (notably Jimi Hendrix, Edie Sedgwick and Judy Garland who all died of a barbiturate overdoses) and amphetamine users (Ayn Rand and J.P. Sartre, as well as many involved with the Warhol Factory crowd of the 1960s, notably the Rolling Stones’ Brian Jones and Bob Dylan) could be expanded on, the examples above should suffice as a pretty thorough sampling of some illustrative cases of the connection between artistic and scholarly genius and addiction.

Musical artists like the Beatles, the Byrds and Bob Dylan released some of their best albums in their ‘drug phase.’ And some of our most cherished literary compositions of recent years, especially works by many of the Beat writers, were works of men who were experimenting with the effects of drugs on their creativity, men who were willing as Rimbaud writes to “disorganiz[e] all the senses” and to “suffer” in order to realize their poetic vision.

We should ask ourselves in reflection if psychedelic albums like the Rolling Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request or the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band would have ever blossomed if not for their experiments with LSD at the time? What about Kesey’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or Burroughs’ Naked Lunch? Do psychedelic drugs have the power to expand our creative potential as Timothy Leary, the scholar branded by President Nixon as “the most dangerous man in America,” famously suggested?

Drugs have a long history in society and drug use can be traced back at least to the ancients, figures who shaped the history of the world as we know it today, and even then it seems our ancestors struggled with moderation, or so we could guess from the philosophies of Socrates which were handed down to us by Plato.

In the modern world, certain drugs have gone through periods when their use was encouraged for medical purposes and times when they have been prohibited by law. Cocaine and opium, once popular medicinal drugs, the former also a key ingredient in the original recipe for Coca-Cola, are today considered dangerous psychoactive substances. The negative side effects of many of these drugs (legal and illegal) are well-known: mental impairments, earlier onset of psychosis in those predisposed to mental illness, decreased liver and kidney functions, heart problems, increased risk or certain cancers and even death. For this reason, and likely because of the educational efforts put out to support the war on drugs, much writing in recent years has focused solely on the problems of drugs and addiction.

We, as a society, feel a certain loss when we lose prematurely great actors like Philip Seymour Hoffman, comic geniuses like John Belushi, music legends like Jimi Hendrix, Keith Moon and Janis Joplin, and brilliant poets like Dylan Thomas who open up our understanding of our world. But, it is also very possible that these figures, all geniuses in their own right, may never have fully realized their potential if not for their use of mind-expanding substances. It is likely that their addictions fanned the flames of their creative genius. But it is unlikely that if not already creative masterminds that they would have created such lasting and life-changing works, for as Balzac writes, “Many people claim coffee inspires them, but, as everybody knows, coffee only makes boring people even more boring.” We could well replace the word “coffee” here with absinthe, opium or cocaine.

Sgt. Pepper – the Beatles’ psychedelic, LSD-driven album – is ranked at the top of Rolling Stone’s list of the greatest albums of all time. Blonde on Blonde, Dylan’s amphetamine-drenched two-disc LP, isn’t far behind, at number nine. Some of our most beloved and critically acclaimed artists, writers, poets and philosophers were alcoholics and addicts. They produced works of genius and cultural significance, but at what cost?

Many of them suffered from mental health issues and others struggled with life problems, finding substance abuse necessary to cope with their everyday lives, including for some the problem of life in the spotlight. As Freud suggests in his classic work, Civilization and Its Discontents, “Life, as we find it, is too hard for us; it brings us too many pains, disappointments and impossible tasks. In order to bear it we cannot dispense with palliative measures. . . .There are perhaps three such measures: powerful deflections, which cause us to make light of our misery; substitutive satisfactions, which diminish it; and intoxicating substances, which make us insensible to it.”

In today’s society, we tend to focus on the artist’s use of drugs as a social problem of great concern. Following Philip Seymour Hoffman’s death, much din was made about the need to recognize the problems of addiction and of the need for more effective treatment efforts, including the expansion of anti-overdose drugs. It is well-established that substance abuse brings with it many problems, but are there – dare it be said – benefits to the use of substances, in that they push open the floodgates of our minds? There is scholarly research that supports this, and the late Steve Jobs stated not long before his death that his experimentation with psychedelic drugs was “one of the two or three most important things” he had done in his life, crediting these experiments with his expansive creativity.

Addiction – be it to legal or illegal substances – may be one of the great social ills of civilization, but the use of “intoxicating substances” may not only be useful for dealing with the “pains, disappointments and impossible tasks” of everyday life (including for the celebrity, life in the public eye), but it may be relevant and even beneficial to the creative process. Drugs have claimed the lives of too many too soon and have pushed some to madness, and have destroyed many lives and careers, but they have also led to the blossoming of mind-bending imagery, wild and mercurial wordplay and musical composition and works of art and philosophy that have altered our entire worldviews. Substance abuse is like so many elements of our society, a ball of contradictions, a social problem that can lead one down a rapidly descending path of self-destruction and, simultaneously, a creative fuel that thrusts forward ideas that have changed the world.

Author Bio:

Benjamin Wright is a contributing writer at Highbrow Magazine.

For Highbrow Magazine

Photos: Lloyd Arnold (Wikimedia, Creative Commons); Chris Hakkens (Wikipedia, Creative Commons); Wikipedia (Creative Commons)